Baengnyulsa Temple – 백률사 (Gyeongju)

Temple History

Baengnyulsa Temple is located just to the north of Bunhwangsa Temple in Gyeongju on Mt. Sogeumgangsan (176.7 m). Supposedly, and according to the Samguk Yusa, the temple was built to commemorate the martyrdom of Ichadon (501 – 527 A.D.). Originally, the temple was called Jachusa Temple. In English, “ja” means “pine nuts,” while “chu” means “chestnut.” Later Jachusa Temple changed its name to Baengnyulsa Temple. It was common at this time in Korean history, during the Silla Dynasty (57 B.C. – 935 A.D.), that if a temple had the same sound and/or meaning, the name of the temple could change. With this in mind, “baek” means “pine nut” in English, while “yul” means “chestnut.” So even though the name of the temple changed, it retained the same meaning as the previous temple name of Jachusa Temple. So Baengnyulsa Temple means “Pine Nut Chestnut Temple” in English.

The temple was later destroyed by fire during the Imjin War (1592-1598). The temple was rebuilt during the reign of King Seonjo of Joseon (r. 1567 – 1608). And the present Daeung-jeon Hall was later rebuilt during the 1800’s. It was also around this time that the temple was renamed Baengnyulsa Temple.

The Daeung-jeon Hall, which is a Cultural Properties Material, once contained a bronze statue of Yaksayeorae-bul (The Medicine Buddha). This statue, which is National Treasure #28, was first created in the mid-8th century. It stands an amazing 1.77 metres in height. The statue has a relatively small body when compared to its face. It has a round face with an elegant expression. It has long eyelashes, almond-shaped eyes, a sharp nose, and a small mouth. The robe of the statue is draped tightly around the shoulders and body of Yaksayeorae-bul. The belly of the Buddha protrudes outwards, and his chest leans backwards. Unfortunately, the statue’s two hands have been cut off and are now missing. This statue is considered one of the three greatest gilt-bronze Buddhist statues made during Later Silla (668-935 A.D.). This alongside the Birojana-bul of Bulguksa Temple (N.T. #26) and the Seated Amita-bul of Bulguksa Temple (N.T. #27) comprise the list of three. All three were made around the same time. However, while the Gilt-bronze Standing Bhaisajyaguru Buddha of Baengnyulsa Temple was originally housed at the temple, since 1930, it’s been housed at the Gyeongju National Museum.

The Ichadon Myth

Historically, and drawing on the vital importance of the temple’s significance to the growth of Buddhism in the Silla Kingdom, is the story that centres on the death and martyrdom of the monk Ichadon (501-527 A.D.). In both the Samguk Sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms) and the Samguk Yusa (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms), Ichadon is referred to as the nephew of King Beopheung (r. 514 – 540 A.D.). “Ichadon,” according to David Mason’s website, is an honorific title bestowed upon the monk who was a young Silla Kingdom aristocrat.

During the early reign of King Beopheung, the king wanted to establish Buddhism as a state religion in the Silla Kingdom. In the Samguk Yusa it has King Beopheung stating, as he contemplatively overlooked his land, “The Han Emperor Ming-ti received a revelation from Buddha in a dream before the flow of Buddhist teachings to the East. I wish to build a sanctuary in which all my people can wash away their sins and receive eternal blessings.” King Beopheung’s alluding to Emperor Ming of Han (r. 57 – 75 A.D.) is a reference to the spread of Buddhism in China during the Han King’s reign.

More pragmatically, the reason that King Beopheung wanted to established Buddhism as a state religion was to help strengthen the central role of Silla royal power. This had already been done in the neighbouring Baekje (18 B.C. – 660 A.D.) and Goguryeo Kingdoms (37 B.C. – 668 A.D.), when the Goguryeo Kingdom officially recognized Buddhism as the state religion in 372 A.D., which was subsequently followed by the adoption of Buddhism as a state religion in the Baekje Kingdom in 384 A.D. However, Silla state officials opposed this idea. In fact, Buddhism was declared illegal up until 527 A.D., when the actions of Ichadon changed the trajectory and acceptance of Buddhism in the Silla Kingdom.

According to the Samguk Yusa, once more, in 527 A.D., Ichadon and King Beopheung came up with a solution to help circumvent the stubbornness of the royal court so as to allow the Silla Kingdom to finally establish Buddhism as a state religion. When talking about the state courtiers, King Beopheung made this comment, “Because of my lack of virtue heaven and earth show no harmonious signs and my people enjoy no real happiness. I am therefore minded to turn to Buddhism for the peace of my heart, but there is no one who can assist me.”

However, in the royal court there was a minor official with the rank of Sa-in. His family name was Bak. His honourific title was Ichadon, and his other name was Yeomchok, which is a play on words for porcupine. And while his father was undistinguished, his great grandfather had been a Galmun-wang (which is the title given to a father of the reigning king).

As described in the Samguk Yusa, “Yeomchok’s steadfast loyal heart was like a straight bamboo or an evergreen pine tree and his morals were as clear as a watermirror.” Because of these attributes, it was probable that Ichadon would be promoted to a high office in the king’s court.

Looking at King Beopheung, Ichadon could read the king’s mind. In doing this, Ichadon said, “The sages of old would lend their ears even to men of low degree if they gave wise counsel. Since I know Your Majesty’s mind, I will dare to say a few words. As the song of birds herald the approach of spring, so the gush of blood from my neck will foreshadow the full bloom of Buddhism, for in my spouting blood the people will see a miracle.”

King Beopheung answered, “‘For mercy’s sake,” cried the King, ‘that is not a thing for you to do.’

“‘A loyal subject will die for his country,’ Yeomchok replied, ‘and a righteous man will die for his king. If you cut off my head to the stubborn courtiers, who will never believe in Buddha unless they are shown a miracle, the myriad of people prostrate themselves before your throne and will worship Buddha.'”

The king answered, “Though I desire to save my people, how can I kill an innocent man like you? You would do better to avoid this fate.”

Ichadon answered, “One man’s earthly life is dear…but the eternal lives of many people are dearer. If I vanish with the morning dew today, the life-giving Buddhist faith will rise with the blazing sun tomorrow. This will bring peace to your heart.”

Finally, the king relented, “If you have set your heart on advancing the spread of Buddhism by the sacrifice of your life, you are a great man.”

After this conversation with Ichadon, the king called all of his courtiers into a royal conference where he threatened the lives of his courtiers because they wouldn’t allow him to adopt Buddhism as a state religion. And the focus of King Beopheung’s ire, as was pre-planned, was Ichadon.

King Beopheung said to Ichadon, “You too hindered my orders and miscarried my messages. Your crime is unpardonable and you shall die. You shave your head and wear a long robe, you utter strange words – ‘Buddha is a mystery, Buddhism gives life.’ Now let your Buddha perform a miracle and save your life.” It would seem that Ichadon had actually already become a monk at this point.

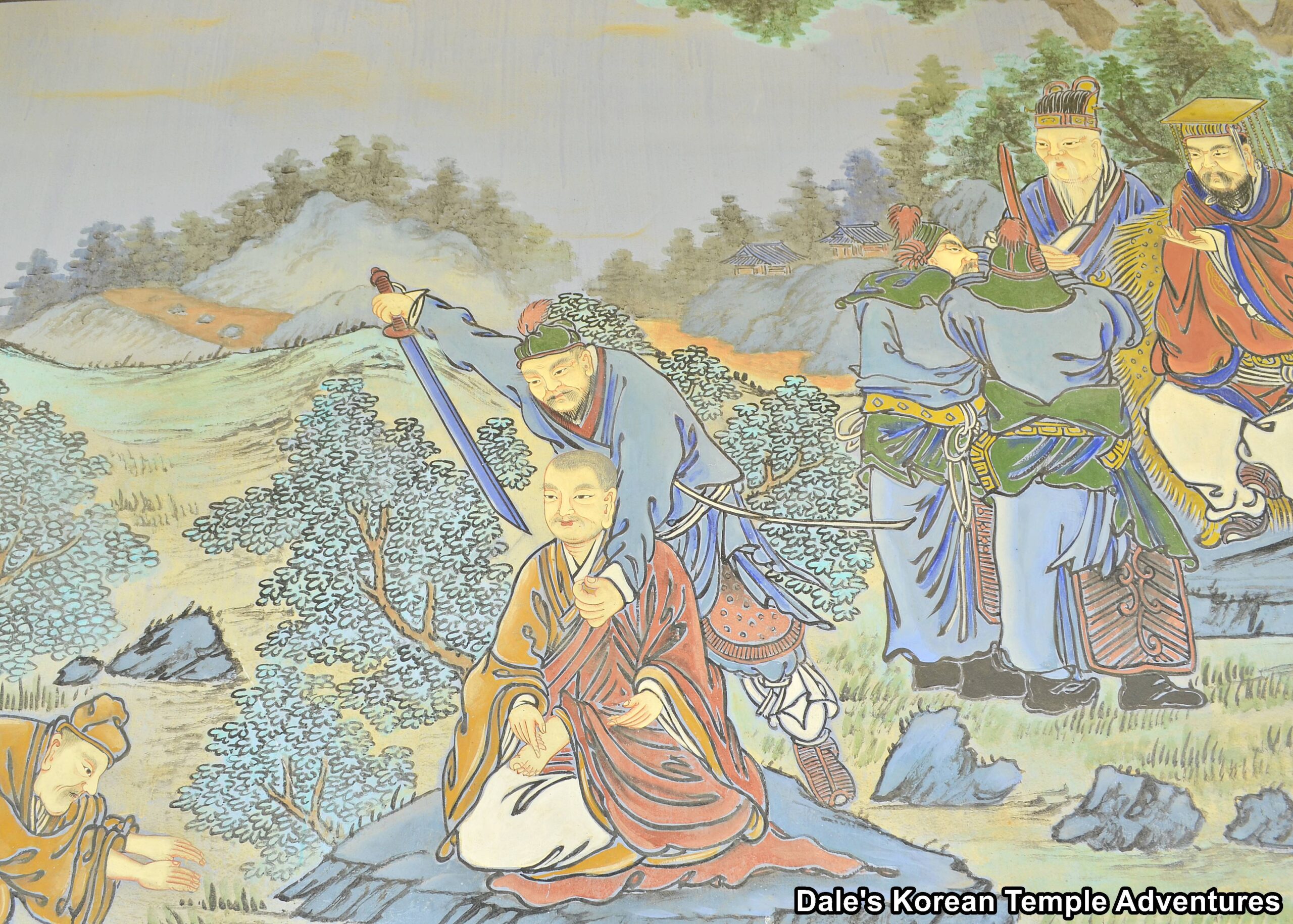

On the day of Ichadon’s execution, and as the executioner raised his sword, the king, courtiers and citizens that had gathered to witness the monk’s death all looked away. Looking up to heaven, Ichadon said, “I die happy for the sake of Buddha. If Buddha is worth believing in, let there be a wonder after my death.”

After his execution, and according to the Samguk Yusa, “Down came the sword on the monk’s neck, and up flew his head spouting blood as white as milk [white being the most sacred colour in Korean culture, according to David Mason]. Suddenly dark clouds covered the sky, rain poured down and there was thunder and lightning…tigers ran and dragons flew, ghosts mourned and goblins wept. It seemed that heaven and earth had turned upside down. From afar came the sound of a bell as the Bodhisattva of Compassion [Gwanseeum-bosal] welcomed the martyr’s fragrant soul into the Lotus Paradise.”

King Beopheung wept after Ichadon’s death, and Ichadon’s childhood friends held onto the monk’s casket and wept, as well. Afterwards, onlookers praised Ichadon’s sacrifice for the support of King Beopheung’s Buddhist faith.

Ichadon’s childhood friends would then bury the monk’s headless body on the western peak of Sogeumgangsan. This mountain was named after the Diamond Sutra in Buddhism. Also, Mt. Sogeumgangsan was the northern sacred peak of the city of Gyeongju. And according to Pungsu-jiri (geomancy), the north direction is the direction for death. Furthermore, legend has it that Ichadon’s body was buried in the same place where his head had flown and fallen on Mt. Sogeumgangsan.

Some of this information comes courtesy of my friend David Mason’s amazing website. Please check it out here!

Temple Statue Myth

According to the Samguk Yusa, “On the southern side of this mountain [present day Mt. Sogeumgangsan] is a temple called Baengnyulsa Temple, and seated in its Golden Hall [main hall] is a Buddha image which has worked many wonders.”

The history of the statue is unknown, and it shouldn’t be confused with the bronze statue of Yaksayeorae-bul that’s National Treasure #28. According to this temple myth, this statue was made by heavenly sculptors from China. Furthermore, the statue is believed to have ascended to Doricheon (one of the thirty-three Buddhist heavens), where it re-entered the Golden Hall at Baengnyulsa Temple after stamping its feet on the stone steps at the entrance to this temple shrine hall. This stamping left footprints, which at the time of the Samguk Yusa’s writing, could still be seen.

According to another myth also in the Samguk Yusa about this Buddhist statue, it concerns the return of Buryerang, a famous Hwarang (Flower Youth). The statue saved Buryerang from pagans to the north, who were the enemies of the Silla Kingdom. Buryerang was King Hyoso of Silla’s favourite Hwarang. And because he was a favourite of the king’s, King Hyoso of Silla (r. 692-702 A.D.) placed a thousand youths under the command of Buryerang.

So in March, 693 A.D., Buryerang led a group of his followers to Gangwon-do Province for pleasure. However, when they arrived at Wonsan (in present day North Korea), they were attacked by a band of armed thieves and Buryerang was taken captive. Buryerang’s followers fled for their lives, but An Sang, a lieutenant in Buryerang’s forces, stayed with his master in their enemy camp.

Hearing this, King Hyoso of Silla was at a loss. He said to his courtiers, “Since my royal father handed down the sacred flute to me, I have kept it safe in the High Heaven Vault together with a hyeon-geum (a harp with six silk strings), which protects us from all evils with their holy might. Why has my favourite Hwarang fallen into the hands of thieves?”

Suddenly, a large collection of clouds gathered around the High Heaven Vault. Troubled by these clouds appearance, the king had his servants examine the interior of the vault. It was only then that they discovered that the two treasures, the harp and the flute, were missing. Angered by the loss of these instruments and Buryerang, King Hyoso of Silla had the five vault-keepers imprisoned.

The next month, in April, King Hyoso of Silla offered a reward to anyone that could recover the musical instruments. In addition to this reward, the king would also allow the individual to have a one year exemption from paying taxes.

As the king was mourning his losses, the parents of King Buryerang prayed in the Golden Hall at Baengnyulsa Temple every night until May 15th. These prayers centred on the safe return of their son. It was on the night of May 15th that they found a harp and flute on the table of the incense burner and Buryerang, as well. Along with An Sang, they were standing behind the Buddha image inside the Golden Hall at Baengnyulsa Temple. Surprised, and still in shock, they asked their son how he had returned to them in Gyeongju.

Buryerang said, “My honoured parents, when the enemy carried me away, they made me a cowherd of Daedo-kura, their chief, and I was set to caring for his cattle in the field of Daejo-rani. There was a kind monk holding a harp in one hand and a flute in the other that appeared and said, ‘My good lad, don’t you feel homesick?’

“‘Partly overawed by this noble face and partly overcome with grateful emotion at his gentle words, I fell to my knees and answered, ‘Honourable monk, carry me back to Gyeongju. I long to see my king and my parents in my native land, a thousand li far away to the south.’

“‘Come with me, my lad,’ he interposed, and took me by the hand and led me to the seacoast, where I met An Sang, once again. Here the monk broke the flute in two and handed each of us a piece, ‘Ride on them!’ he said, while he rode the harp. We flew high above the clouds and in a twinkling we had landed here.”

Eventually, all of this was reported to King Hyoso of Silla. The king praised Buryerang’s valour and good fortune. As a result, King Hyoso rewarded the flying monk of Baengnyulsa Temple with two sets of gold dishes each weighing fifty yang, five fine robes, 3,000 rolls (one roll was forty yards) of gray hempen cloth, and 1,000 gyeong of farmland to “reward the grace of the Buddha.”

According to the Samguk Yusa, “There are endless tales of the wonders wrought by the Buddha of Baengnyulsa Temple, all of them indescribably interesting.”

Lastly, this magical statue at Baengnyulsa disappeared during the Imjin War (1592-1598) never to be found again.

Temple Layout

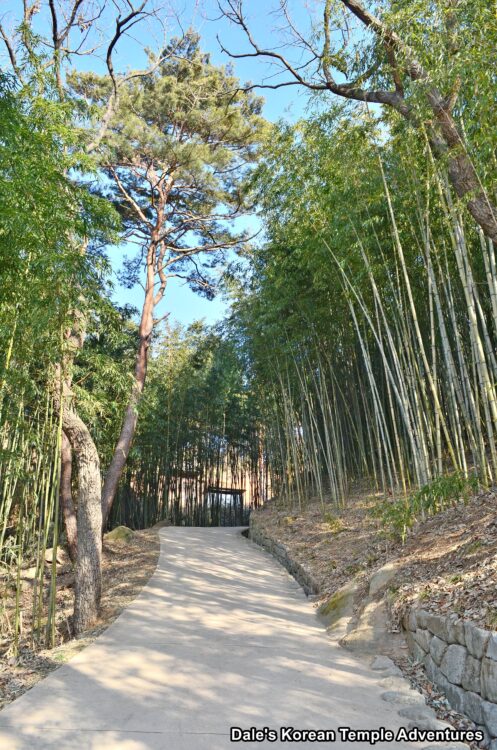

You can approach Baengnyulsa Temple in one of two ways. The first is past the Gulbulsa-ji Temple Site and up a three hundred metre long trail that bends in the midst of a bamboo forest. The other way is up a steep set of side-winding stairs to the right of the temple complex. If you take the Gulbulsa-ji Temple Site trail, you’ll approach Baengnyulsa Temple from the rear. And if you take the other steep side-winding set of stairs, you’ll approach from the front of the temple, but you’ll miss out on visiting the amazing Gulbulsa-ji Temple Site.

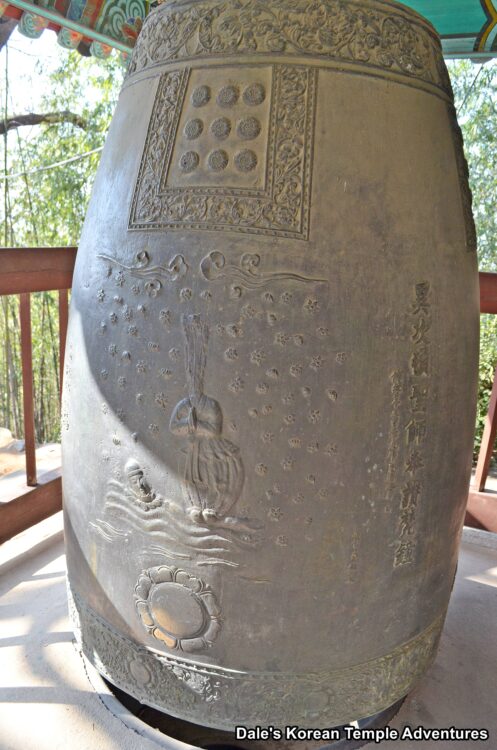

For the sake of this post, we’ll approach from the front of the temple grounds. You’ll see Baengnyulsa Temple appear over the folds and forest of Mt. Sogeumgangsan. Now standing in the lower courtyard at Baengnyulsa Temple, you’ll see the Jong-ru (Bell Pavilion) to your left. You’ll also notice the monks dorms to the rear of the bell pavilion, as well. Have a close look at the Brahma Bell inside the Jong-ru. If you look close enough, you’ll notice that it depicts the martyrdom of Ichadon.

To the right of the Jong-ru, and up a small set of stairs, is the Daeung-jeon Hall at Baengnyulsa Temple in the upper courtyard. The exterior walls to the main hall are all but unadorned except for the dancheong colours. As for the interior, and resting on the main altar, you’ll see a triad centred by Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha). This central image is joined on either side by Munsu-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Wisdom) and Bohyeon-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Power). All three appear under a large datjib (canopy). To the right, and rather interestingly, is a compact shrine with statue and paintings dedicated to the Nahan (The Historical Disciples of the Buddha). And to the left of the main altar is a fierce Shinjung Taenghwa (Guardian Mural), as well as a beautiful painting dedicated to Ichadon.

Behind the Daeung-jeon Hall, and up a long set of stairs, is the Samseong-gak Hall. The exterior walls are adorned with Sinseon (Taoist Immortals), as well as an intense mountainside tiger. As for the interior, there are three rather plain shaman murals dedicated to Sanshin (The Mountain Spirit), Chilseong (The Seven Stars), and Dokseong (The Lonely Saint).

How To Get There

The easiest way to get to Baengnyulsa Temple is by taxi from the Gyeongju Intercity Bus Terminal. The ride takes about fifteen minutes, and it’ll cost you around 5,000 won. The cheaper way to get to Baengnyulsa Temple, on the other hand, is to take city Bus #70 from out in front of the Gyeongju Intercity Bus Terminal. The bus ride will take about forty minute, and it’ll let you off in the temple parking lot. From the temple parking lot, you’ll need to walk an additional five hundred metres up a steep path, and past Gulbulsa-ji Temple Site, to get to Baengnyulsa Temple.

Overall Rating: 7/10

Baengnyulsa Temple has one of the most important pasts that any Korean Buddhist temple can possess. It has two great myths, one of which details the impetus for the spread of Buddhism throughout the Silla Kingdom. Adding to the martyrdom of Ichadon, as well as one of the more fantastical myths about a statue at a Korean temple, is the beautiful Daeung-jeon Hall with all of its artwork. Also, Baengnyulsa Temple is scenically located on Mt. Sogeumgangsan with amazing vistas of Gyeongju down below. While not all that well known, Baengnyulsa Temple makes for quite the adventure into Korea’s past.