Colonial Korea – Gyeongju

Introduction

In general, there were numerous reasons as to why the Japanese were so focused on archaeology throughout the Korean Peninsula. One of the reasons was to portray the Korean colony as inferior to Japan and in need of civilizing. Another reason was to justify the annexation of Korea through tourism and conservation that had previously been overlooked by the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). And the subsequent revenue would help the Japanese war effort in China. Finally, the other link that the Japanese attempted to form through these archaeological endeavors was to form a bond that united the two people through a form of pan-Asian Buddhism to help combat Western and Christian influences.

More specifically, the reason for these restorative acts on Korean Buddhist artifacts and sites were in line with the Japanese thought that “Buddhism was the core of the Eastern Spirit,” which was an idea pursued by the Japanese since the Meiji era (Jan 25, 1868 – Jul 30, 1912). Additionally, it was the cultural assets of Korea that the Japanese placed the greatest value upon, which were created before the Joseon Dynasty. The reason for this is that the Japanese were attempting to evoke in the minds of Koreans the memory of cultural achievements founded during the “Buddhist era” that predated the Joseon Dynasty. Japan needed to point to a pre-modern era that predated the “ruin” of Korea. This “ruin” had been brought on by the rulers of Joseon that were anti-Buddhist. According to the Japanese, the glory of Korea lay in its distant past that had flourished when Buddhism was at the very heart of its society and its successes. So it made sense to attack Joseon rule, while elevating what came before it. It fed into the narrative that Japan had to promote Buddhism which linked the two people together, supported tourism, and combated Western-influence.

These repairs and restorative efforts were then carried out on artifacts across various regions in Korea. However, among these efforts, most of this work was concentrated on Silla Buddhist artifacts and sites in the former Silla capital of Gyeongju.

Bulguksa Temple

In Gyeongju, Japanese authorities paid particular attention to two sites: Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Hermitage. In restoring Bulguksa Temple, and for almost all sites in Gyeongju, the Japanese authorities didn’t consult the original floor plans or diagrams. There are a couple reasons for this. The first is that most historic sites had fallen into disrepair through neglect and the original floor plans simply didn’t exist. And the second is that the Japanese didn’t consult Koreans; instead, the Japanese used their own judgment and ultimate authority in reconstructing temples like Bulguksa Temple.

Bulguksa Temple, when the Japanese took control over the Korean Peninsula, had fallen into disrepair for decades. The temple had come to be badly neglected and partially looted. With all this in mind, and with the Japanese attempting to pursue their previously mentioned archaeological goals, Japanese authorities attempted to put Bulguksa Temple back together again. There are examples where the Japanese seem to have made mistakes with the overall layout of the temple grounds. For example, the Beomyeong-ru Pavilion (Floating Reflection Pavilion) and the Jwagyeong-ru Pavilion (Sutra Pavilion) don’t appear in the photographs or temple floor plans prepared by the “Oriental Society” (Toyo kyokai 東洋協會) in 1909, when Bulguksa Temple was originally surveyed by the Japanese.

Another major difference we see today is that the entire lower courtyard that includes the Daeung-jeon Hall and the Geukrak-jeon Hall have corridors. At the time of the Japanese reconstruction, only the corridors seem to have existed in the floor plans around the Daeung-jeon Hall and the Museol-jeon Hall (which is located to the rear of the main hall).

There are numerous other discrepancies at Bulguksa Temple that were made during Japanese occupation that could probably have been set straight through further archaeological investigation, but without any original floor plans from the Joseon Dynasty, the Japanese did what they could and wanted to do. Other discrepancies include the location of the Geukrak-jeon Hall. According to the “Oriental Society” floor plans, this hall was originally the Wichuk-jeon Hall (The Invoking Blessings Hall). And the monk living quarters were located to the left and right of the Geukrak-jeon Hall. The Anyangmun Gate, which stands out in front of the Geukrak-jeon Hall, originally stood slightly in front of its current location.

As for the current configuration of Bulguksa Temple, two shrine halls seem to be absent from the “Oriental Society” floor plans. They are the Hyangro-jeon Hall (The Incense Burner Hall) and the Sipwang-jeon Hall (The Ten Kings of the Underworld Hall). It appears as though they probably existed on the current site of the Beophwa-jeon Hall (Lotus Sutra Hall).

There is a slight caveat to the Japanese efforts to restore Bulguksa Temple and the difficulty they had in reconstructing the temple to its former design. The caveat is this: there’s no way of knowing if what the Japanese did was true to the original floor plan. And the reason for this is that there is no way of knowing that the floor plan that the Japanese were working from was the original layout of the temple from its original creation by Kim Daeseong (700-774 A.D.) in the eighth century. It would appear that the original layout of the temple grounds had changed from the time of Kim Daeseong to when the Japanese authorities attempted to piece Bulguksa Temple back together again.

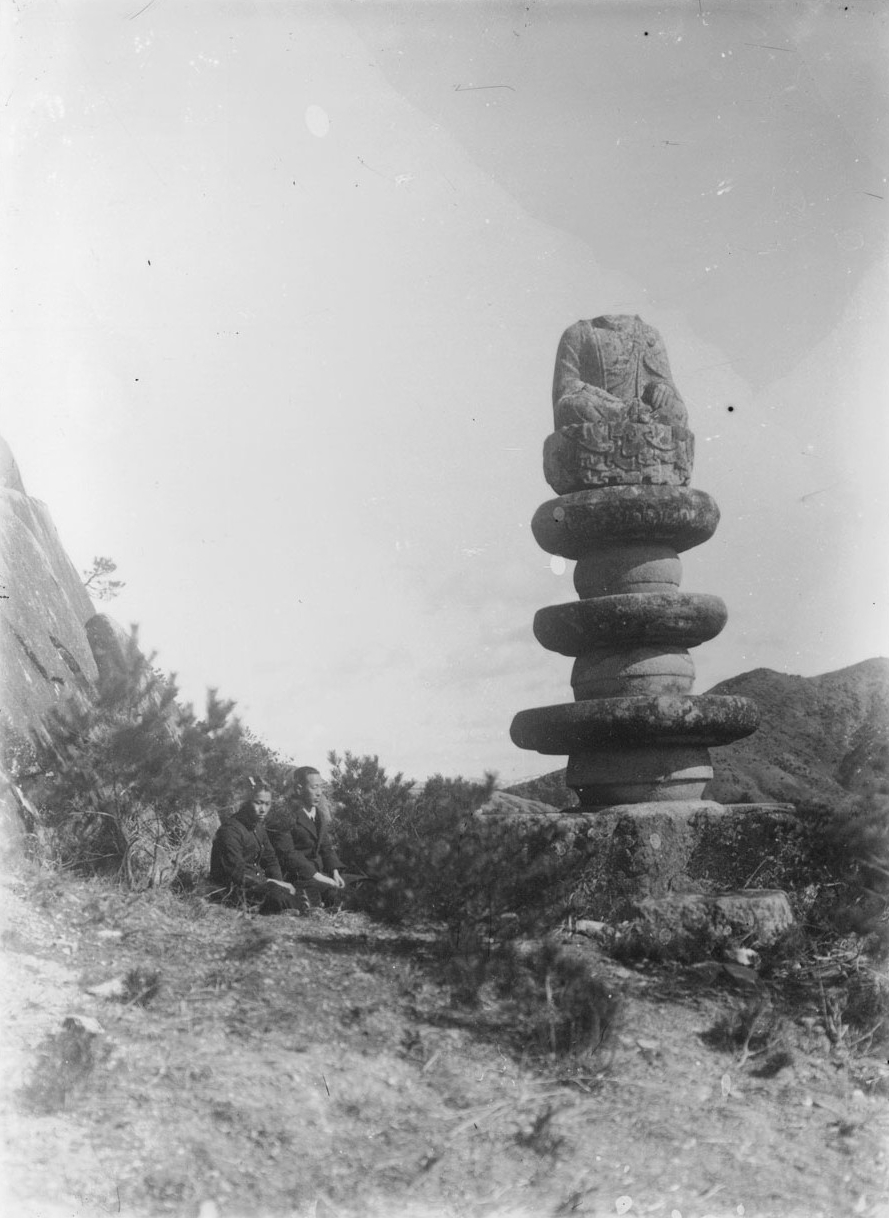

As a bit of of an aside, one of the more interesting tales about Bulguksa Temple during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945) concerns the “Stupa of Bulguksa Temple,” which is now located to the rear of the temple grounds next to the Biro-jeon Hall. This stupa was originally recorded in Dr. Sekino’s first report on Bulguksa Temple. However, the photograph from this report doesn’t show the capstone or upper part of the wheel-shaped finial. However, it later appears in the photos in an essay entitled “Cultural Relics of the Silla Dynasty in Korea’s Gyeongju,” which was published in volume one of “Toyo kyokai chosabu gakujutsu hokoku 1 – Academic Report of Investigations by the Oriental Society.” It’s unknown whether the capstone belonging to the stupa was later found nearby and attached or whether a capstone of similar size was roughly aligned and placed atop the stupa at the time of Sekino’s report.

More specifically, the “Stupa of Bulguksa Temple,” in 1905, was taken out of Korea and brought to Ueno Onshi Park in Tokyo by the Japanese. And it was owned by Nagao Kinya. However, this is only part of the story. According to the Korean newspaper, the Maeil Sinbo, someone from Kaesong (Gaeseong), convinced a monk at Bulguksa Temple to sell the stupa, which he did. The stupa was then transported to Tokyo by boat at night. The “Stupa of Bulguksa Temple” would eventually be returned to Korea in June, 1933.

Seokguram Hermitage

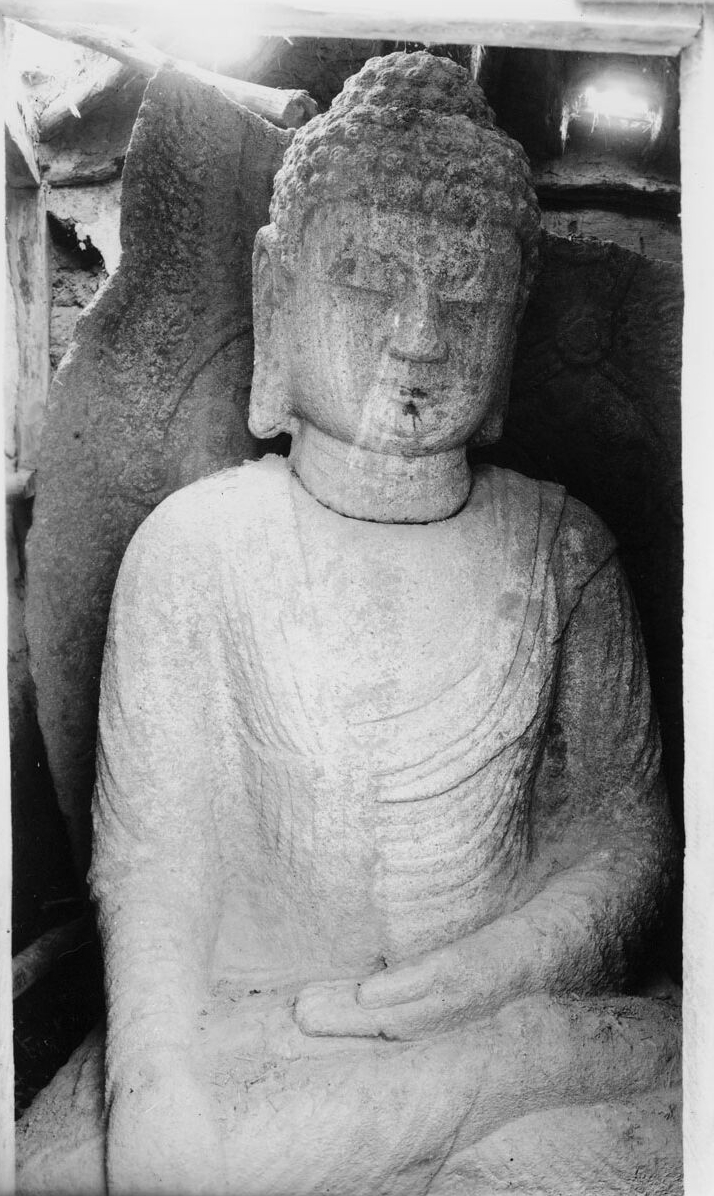

The other major site that the Japanese focused on extensively in Gyeongju was Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto. With the annexation of Korea by the Japanese in 1910, the Governor-General of Chosen repair on Seokguram Hermitage began almost immediately. Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto was one of the main reasons that Gyeongju grew to such prominence. This is demonstrated by newspaper articles that applauded the stone hermitage.

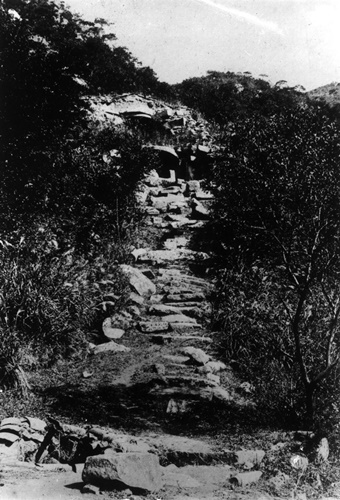

In the past, Seokguram Hermitage, and specifically the famed grotto, had been used as a scenic spot for the yangban, a site for prayer by the Buddhist community, and a place to relax by commoners out for a hike or a picnic. However, at the end of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto had fallen into disrepair. It took the efforts of Japanese engineers employed by the Japanese Colonial government to repair Seokguram Hermitage. This started in 1913, and it took place over two years under the instruction of Governor-General Terauchi Masatake (1852-1919). However, with the Japanese repairing the Seokguram Grotto, the meaning behind its functionality changed from a religious one to one of aesthetic beauty as a piece of art.

In a poem-like essay, Asakawa Noritaka, who visited Seokguram Hermitage in 1921 and who was known for his research on Korean porcelain, wrote about the grotto. In his writing, he wrote about how the grotto awakened a certain sense of Toyo (the Orient/the Far East). Asakawa would go a step further by attempting to read the minds of the Silla people who originally built Seokguram Hermitage atop Mt. Tohamsan. According to Asakawa, Seokguram Hermitage was built so that the Buddha could protect sea travel between Silla and Nara, Japan. He also believed that there was a “unilinear flow of beauty” that was created by Tang China, continued in the Baekje Kingdom, migrated onward to the Silla Kingdom, and eventually arrived in Nara, Japan. The symbol and artistry found in the Seokguram Grotto, according to Asakawa, called for a revival of the great Orient. Asakawa would write, “Eternal Seokguram, you who speak the words of God/May the people of the Orient return to their homeland deep in your heart.”

So it seems rather obvious that the goal of Japan was twofold. The first was to allow the Seokguram Grotto to symbolically act as the pinnacle of Buddhist artistry, while also acting as a way to unify various nations within the purview of Japanese Colonial rule and expansion. The Japanese would disguise these motives in a couple of ways; namely, tourism and archaeologically, but the root of Japan’s efforts was to unify the colonial subjects under Japan’s colonial rule. But for this to take place, there were a few things that first needed to take place.

On September 20, 1923, about a month after further repair work was completed on the Seokguram Grotto, the Maeil Sinbo newspaper carried an article entitled, “Historic Remains in the Old City of Silla.” This article carried a picture of the grotto in it. The article would state that the Seokguram Grotto was “a collection of incomparable flowers of Oriental art.” In another newspaper, the Donga Ilbo, dated June 30, 1923, in a series entitled “Miracles of the World,” encouraged a sense of national pride in the supreme artistry found inside the grotto at Seokguram Hermitage. The newspaper would go on to state that the image of the Buddha inside the grotto was “the greatest of the oldest artworks in Asia.” The newspaper, by focusing on the Seokguram Grotto, was attempting to appeal to a sense of nationalism in the framework of a pan-Asian Buddhism.

Another way that the Japanese would use Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto was to transform the image of the Buddha from Buddhist rituals to that of a world class piece of artwork. Before the Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto was elevated, Japanese art historians were traveling throughout the capitals of western countries and their museums. In doing this, and viewing Christian art, the Japanese art historians would attempt to elevate historical Buddhist images from Buddhist ritual and make them artwork in their own aesthetic right much like what had happened to Christian art in western nations. Not long after this exploration and discovery, Western-style institutions such as exhibitions and art schools were open in Japan. Also, famous artisans of Buddhist images were hired as university professors. Then in 1873, at the Vienna World Exhibition, a large Buddha image from Kamakura was put on display. So as a result of the introduction of the Western concept of art, as introduced and influenced by the Japanese during Japanese Colonial Rule over the Korean Peninsula, this idea would transform and influence how the world and Koreans would view their Buddhist icons and images. And at the heart of this transformation was the Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto. This would start from the 1910’s.

The first attempted elevation of Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto beyond its religious iconography was taken by Yanagi Muneyoshi (1889-1950). In the publication “Geijutsu,” Yanagi wrote an article entitled “On the Sculptures of Seokguram,” which was published in June, 1919. Yanagi would state in this article about the Seokguram Grotto that it was “…not just the work of one country but a crystallization of the Buddhism of Sui and Tang China and of Oriental religion and art.” This quote squarely places Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto in a line of Buddhist artistry from China to Japan, as well as elevating and separating the Buddhist images from their original meaning rooted in Buddhism and attempting to elevate them as a piece of art.

This approach by Yanagi, and its indifference to how Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto had previously been experienced by Koreans, was secondary to the way that Japanese authorities now intended to interact with the icons inside Seokguram Grotto. This was very much of an attitude of the colonizer ruling the colonized. This approach highlighted the Japanese efforts to be the ultimate authority over the meaning and uses of Korean Buddhist icons through the interpretative-lense of Japanese Imperialism.

The way in which Yanagi is able to detach Buddhism from the Buddhist icon at Seokguram Hermitage and grotto is that he grounds the creation of the grotto in the individual mind of Kim Daeseong. By doing this, the statues inside the grotto first appears as an interpretative artwork that is only later grounded in Buddhism. This is a rather odd way to attempt to separate the religious from the religious statue, but it was something that Yanagi committed to and promoted. This is only one example of what the Japanese attempted to do with all Buddhist images in Korea and not just in Gyeongju or Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto.

This ideology by the Japanese was furthered by Inoue Tetsujiro (1855-1944), who was a Japanese religious studies scholar and a pioneer of comparative religions in Japan. He was quick to focus on what he thought of the connection found between India, China, Korea, and Japan. He believed that Buddhism was as great and universal a religion as Christianity in the West. In fact, Inoue believed that Buddhism wasn’t just equal to Christianity, but that it was in fact superior to Christianity in its Mahayana form and tradition.

So both Yanagi and Inoue were two leading scholars that attempted to put the stamp of Japanese Buddhism and scholarship on Korean Buddhism. Yanagi did this by reinterpreting Korean Buddhists icons as pieces of art, while Inoue was placing Korean Buddhism in the spectrum of Mahayana Buddhism from India, to China and Korea, and on to Japan. This spectrum would help, at least in the eyes of Japanese authorities, to unite, in part, the two people, Koreans and Japanese, into one.

After the discovery and the re-interpretation of Seokguram Hermitage and grotto by the Japanese, it quickly helped elevate Gyeongju as a tourist attraction for the Japanese, as well as Koreans, alongside Mt. Geumgangsan. As a result, it was quite common for Gyeongju to become a backdrop for Japanese writers and their experiences on the Korean Peninsula.

Besides the central seated image of Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha) inside Seokguram Grotto, there is also the hidden relief of an eleven-faced image of Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion) directly to the rear of the central seated image of Seokgamoni-bul. People are only able to see this image of Gwanseeum-bosal if they are in fact inside the grotto because it’s obstructed from the front. With the discovery of the Seokguram Grotto by the Japanese, this image of Gwanseeum-bosal came to be admired as the image of Seokgamoni-bul. Examples of its prominent position can be found in Japanese language tourist books that were used for advertising the historic sites of Gyeongju. More specifically, three pictures of Seokguram Grotto were included in a deluxe book edited and published by the “Society for the Preservation of Historic Remains in Gyeongju.” And one of these three images was the image of Gwanseeum-bosal inside Seokguram Grotto. This picture was accompanied with the comment, “It’s carved in such an elegant and elaborate way as to tower over others in the grotto.”

In another publication published by the Japanese, which focused on a series of colonial historiography and archaeology, the image of Gwanseeum-bosal inside Seokguram Grotto appears, once more. This time, and along with an image of Gwanseeum-bosal, is an introduction about the image that reads, “…with the finest craft and the subtlest carving applied, it alone can speak for Buddhist art.”

However, not only did the Japanese have a fascination with Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto, but Koreans had a renewed sense of pride, as well. Gwon Deokgyu (1890-1950), who was a scholar of the Korean language, wrote an essay entitled “Gyeongju Bound,” where he is quoted as saying in this text, ‘‘I heard that Dr. Sekino explained that the Many Treasures Pagoda [Dabo-tap] of Bulguksa Temple, along with Seokguram Grotto, is ‘the ultimate treasure of the world.’” Gwon would continue, “…even possessing insufficient knowledge of architectural engineering, we became proud of ourselves. This derived from Dr. Sekino’s endless praise of the two monuments, saying they were both Korea’s treasure and the world’s at the same time.’’

This pride, not only in Seokguram Hermitage but in all of Gyeongju as the ancient capital of Silla, started with the preservation of Seokguram Hermitage. This preservation was reported by newly emerging Korean language print media as an administrative achievement of the Japanese authorities. More specifically, the “Society for the Preservation of Historic Remains in Gyeongju,” found by local officials in 1911, organized itself around a series of projects, including giving support to the Governor-General of Chosen’s repair work on Seokguram Hermitage and its grotto.

With this support for the Governor General of Chosen’s efforts on Seokguram Hermitage, the society was assigned the right to survey, preserve, and exhibit historical remains in Gyeongju with a specific focus on its connection with Silla. By doing this, the society was highlighting the Buddhist achievements of Silla at the expense of the one thousand years that followed both during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties. The reason for this, rather coyly, was to help heighten the connection that the Japanese were attempting to form between the Japanese and Koreans through Buddhism. The society also took part in developing the historic remains of Gyeongju as a source of income for the tourist industry. This would help Korea gain some much needed revenue, while also helping to support the burgeoning war efforts in China, as well.

Bunhwangsa Temple

Other than Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Hermitage, another focus that the Japanese authorities took was on Bunhwangsa Temple. Japanese researchers, including Dr. Sekino, regarded the stone pagodas of Bulguksa Temple and Bunhwangsa Temple as particularly important Korean cultural assets.

With this in mind, Japanese authorities included Bunhwangsa Temple in a 1904 report that surveyed historic sites in Korea. Included in this report is a photograph of the “Stone Brick Pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple,” which is the oldest pagoda in Gyeongju dating back to 634 A.D. In this picture, the pagoda appears with its base nearly collapsed and its capstone overgrown with weeds and covered in dirt.

One of the ways that the Japanese used photographs and conditions like this was through propaganda. And the way they did this was by juxtaposing images of dilapidated conditions in Korea before Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945) with a repaired and renovated image during Japanese Colonial Rule. One of the ways they specifically did this was in the “Chosen koseki zufu – Illustrated Record of Korean Relics.” In a 1916 photograph of the stone pagoda at Bunhwangsa Temple in this text, two photographs are placed together. One picture is of the neatly repaired pagoda, while the other was taken before Japanese repairs on the structure. The reason this was done was to show the world, including Japanese citizenry, Japan’s intention as a “guardian of civilization” and the “successor of the Eastern Spirit (Buddhism).”

However, while the Japanese did restore the “Stone Brick Pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple,” it’s unclear whether the restoration was loyal to the original design of the pagoda at the time of its creation. While the Japanese specialist probably did save the stone pagoda from collapse, no one knows for sure whether they did a proper job because of a lack of information on the original pagoda’s design. There are two specific examples of this; first, the lion statues that appear on the four corners of the pagoda, were actually scattered around the temple grounds upon their re-discovery. The Japanese authorities then placed these four lions at the base of the pagoda, though it’s unclear if this was their original location. And another example is the foundational embankment that the base of the stone structure now rests upon. It’s unclear if this was the original configuration of the pagoda upon its creation. A lot was unknown, not only about Bunhwangsa Temple but about Gyeongju and its historic sites as a whole; and yet, the Japanese authorities persisted with their efforts.

Historic Statues of Gyeongju

1. Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong

Outside Bulguksa Temple, Seokguram Hermitage, and Bunhwangsa Temple, there are other historic sites in Gyeongju that were of interest to Japanese authorities, as well. One of these historic sites is the “Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong.” Originally, this triad was located further up the mountain at the Seonbangsa-ji Temple Site. According to Sunkyung Kim’s paper, “Research on a Buddha Mountain in Colonial-Period Korea: A Preliminary Discussion,” Kim discusses how a Japanese man by the name of Osaka Kintaro first discovered the triad during Japanese Colonization (1910-1945). Osaka Kintaro was the principal of the Gyeongju public primary school, and upon his arrival in Gyeongju in 1915, Osaka Kintaro had heard rumours about a stone Buddha triad almost completely buried near Poseokjeong on the northwest part Mt. Namsan. However, it wasn’t until 1917 that Osaka Kintaro actually found it after using a local kid’s directions. Then in 1922, anticipating Prince Kotohito’s visit to Gyeongju, who was the Chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff from 1931 to 1940, the “Society for the Preservation of Historical Remains of Gyeongju” wanted to move the triad to their exhibition room. The Society were a group of professionally trained archaeologists, ethnologists, anthropologists, and administrators from Japan, as well as local Koreans. Originally they were known as the “Silla Society.” However, because of the technological challenges of moving such large statues, they ended up leaving the triad where it was on Mt. Namsan.

When Osaka Kintaro later re-visited the triad, he described it in his book “Pastimes of Gyeongju.” Here he described how the locals of Mt. Namsan had started to stack small stones in front of the statue while making a wish. He would go on to describe how he believed that not only was the triad an active place of worship for the locals, but that the entire mountain of Mt. Namsan continued to be a place of worship for Koreans.

The first printed images of the “Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong” appeared in the “Art of Korea’s Gyeongju – Chosen keishu no bijutsu” in 1929 by Nakamura Ryohei. Nakamura Ryohei was a teacher at Ulsan Public School. The photographs in this work show the triad in a similar layout to the present day configurations, while the photos in the “Buddhist Relics of Gyeongju’s Namsan – Keishu nanzan no busseki” from 1940 by the Governor General’s Office of Korea shows a Buddha triad that is collapsed and scattered. It’s unclear when this damage took place; however, judging by the fact that Moroga Hideo, who was a central figure in the “Society for the Preservation of Gyeongju Relics,” asked the Governor General Saito Makoto (1858-1936) for funds for the restoration of the “Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong” in 1923, it can be confirmed that the restoration took place sometime between 1923 and 1929. And the subsequent positioning of the Bodhisattvas to the left and right of the central Buddha might have been designated at this time by the restorative conducted by the Japanese.

2. Rock-Carved Buddhas at Chilbulam Hermitage in Namsan Mountain

Another example of a historic site outside the three major sites in Gyeongju for the Japanese authorities was Chilbulam Hermitage on Mt. Namsan. Much like Bunhwangsa Temple, Japanese authorities attempted to juxtapose the before and after images of the “Rock-Carved Buddhas at Chilbulam Hermitage in Namsan Mountain” in the “Illustrated Record of Korean Relics – Chosen koseki zufu” in 1917 with those found in the “Buddhist Relics of Gyeongju’s Namsan – Keishu nanzan no busseki” in 1940. The former photo shows the central Buddha image with a flat nose from years of wear. The latter photo, on the other hand, shows the damaged nose having been repaired. But not only has the nose been fixed, but the heavily damaged upper left part of the chest and arms have been repaired, as well. This is yet another example of how Japan was attempting to show that not only were they the “successor of the Eastern Spirit (Buddhism),” but that they were also attempting to be the guardians of Korean interests, as well.

3. Stone Buddhas in Four Directions at Gulbulsa Temple Site

Another example of restoration work conducted in Gyeongju was at the Gulbulsa-ji Temple Site on the “Stone Buddhas in Four Directions at Gulbulsa Temple Site.” The “Stone Buddhas in Four Directions at Gulbulsa Temple Site” was first photographed by the Japanese, and Dr. Sekino in particular, in 1904. At this time the stone Buddhas were almost completely buried in dirt on the foot of Baengnyulsa Temple. It was common for silt to wash down from the neighbouring mountain, so it easily accumulated around where the “Stone Buddhas in Four Directions at Gulbulsa Temple Site” was and is located.

With all this in mind, the “Stone Buddhas in Four Directions at Gulbulsa Temple Site” was already partially buried in dirt when the Japanese discovered it. Subsequently, the Japanese published two photographs of the stone Buddhas in 1910 in the “Overview of Korean Art – Chosen bijutsu taikan.” In these photos, the Buddhist sculpture is partial exposed after the removal of some of the surrounding dirt. Besides the upper part of the torso being exposed, the two photos also show the head of the Buddha and the crown of the Bodhisattvas on the left as being damaged. And the Bodhisattva to the right is simply absent from the two photos.

Later, and in the “Illustrated Record of Korean Relics – Chosen koseki zufu” of 1917, there is a photo of the Bodhisattva on the right standing with its upper body damaged. This implies that the “Stone Buddhas in Four Directions at Gulbulsa Temple Site” was restored to its present configuration sometime between 1910 and 1917. In addition to this work, the Japanese also built a stone embankment that was piled up behind the “Stone Buddhas in Four Directions at Gulbulsa Temple Site” to guard against dirt build-up. Once again, the Gulbulsa-ji Temple Site is another example of how Japan was attempting to show that not only were they the “successor of the Eastern Spirit (Buddhism),” but that they were also attempting to be the guardians of Korean interests, as well.

4. Stone Seated Buddha in Yongjangsa-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain

Yet another example of the work conducted in Gyeongju; and more specifically on Mt. Namsan, by the Japanese authorities can be found in the form of the Yongjangsa-ji Temple Site up the Yongjangsa-gok Valley. And particular attention was give to the “Stone Seated Buddha in Yongjangsa-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain” and it’s three-story pedestal on which a headless image of the Buddha rests. This pedestal was damaged up until the early 1920’s. On the stone wall behind the “Stone Seated Buddha in Yongjangsa-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain” is an inscription. This inscription states that the Governor-General of Chosen was ordered to reconstruct the three-story stone pagoda and pedestal that had already collapsed in the twelfth year of Taisho (1923). And the work done to restore the two objects, both the pagoda and pedestal, were completed the following year. However, the 1924 restoration couldn’t completely reproduce the original shape of the pedestal. The way in which the current “Stone Seated Buddha in Yongjangsa-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain” looks in its distinctive features was through the Japanese restoration. It’s believed that current form of the “Stone Seated Buddha in Yongjangsa-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain” was produced from several stones that had been piled up and scattered around the vicinity of the Japanese restoration that took place from 1923 to 1924.

5. Stone Seated Buddha in Mireuk-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain

In comparison to the extensive work done on the “Stone Seated Buddha in Yongjangsa-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain,” other Buddha statues on Mt. Namsan and Gyeongju were only partially repaired. As a result, only relatively minor modifications and repairs were conducted on these stone Buddhas like the “Stone Seated Buddha in Mireuk-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain” which is now located at Borisa Temple on the northeastern part of Mt. Namsan.

In photos from “Pastimes of Gyeongju – Shumi no keishu,” which was published in 1931 by Osaka Kintaro, who had first come to Korea in 1898, the photos of the “Stone Seated Buddha in Mireuk-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain” reveal that the seated stone Buddha was also not intact. Osaka worked as a part-time employee at the “Society for the Preservation of Gyeongju Relics” since 1915 and took a intense interest in the artifacts and historic sites in Gyeongju. Originally, this statue was located in Mireuk-gok Valley and not at Borisa Temple when Osaka took his photos. This was further supported by the report written by the “Society for Research on Korean Relics” in 1938. The statue was moved from its original location in Mireuk-gok Valley to flat ground on Borisa Temple.

Conclusion

At the very heart of Japanese archaeological efforts in Korea; and more specifically, in Gyeongju, was the idea of preservation. And the reason for this preservation was threefold. The first was to help create a bond between the two people through a form of Pan-Asian Buddhism to combat Western influences. Another reason was to help raise capital for both Japan and Korea through tourism. For Korea, it would be to help the impoverished nation, while for Japan it was to help ongoing and future war efforts. And finally, the reason that Japan went to such great lengths to help preserve Korean cultural assets was to help civilize a nation in need of “modernizing” and “civilizing.”

There were various ways in which the Japanese went about this in Korea. Perhaps the most nationalistic was to prey upon the patriotic feelings of Korea. The way the Japanese did this was by pointing back to a time in Korea’s past where Buddhism helped unify and advance the nation as a whole. So the Japanese looked back to the Silla Kingdom, whose capital was located in Gyeongju, to help promote this ideology. The subsequent centuries of Joseon Dynasty rule had only helped to reverse these advancements, in the eyes of the Japanese. That’s why Gyeongju was so important to the propaganda that the Japanese authorities held during Japanese Colonial rule over the Korean Peninsula that helped to subjugate and make Koreans subjects of Imperial Japan.