Haeinsa Temple – 해인사 (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)

Temple History

Haeinsa Temple means “Ocean Seal Temple” in English. The name of the temple is in reference to the “Ocean Seal” samadhi (meditative consciousness) from the Avatamsaka Sutra, or Flower Garland Sutra in English, or Hwaeom-gyeong in Korean. The reason for this reference is the idea that the mind is like the surface of a perfectly calm sea. And it’s from this that the true image of our existence is clearly reflected and everything appears as it is.

Alongside Tongdosa Temple in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do and Songgwangsa Temple in Suncheon, Jeollanam-do, Haeinsa Temple forms the Three Jewel Temples (삼보사찰, or Sambosachal in English). Tongdosa Temple represents the Buddha, Songgwangsa Temple represents the Sangha, and Haeinsa Temple represents the Dharma.

It’s believed that Haeinsa Temple was first established in 802 A.D. by the monks Suneung and Ijeong. However, and predating Suneung and Ijeong founding Haeinsa Temple, there is a legend that claims that the famed Uisang-daesa (625-702 A.D.) first founded Haeinsa Temple in the mid-600s as a hermitage. With that being said, the founding of Haeinsa Temple is more firmly rooted in masters Suneung and Ijeong, who were religious descendants of Uisang-daesa’s Hwaeom-jong, or Flower Garland Sect in English. Haeinsa Temple would become one of the Ten Monasteries of Hwaeom, or the Hwaeom Sipchal in Korean. Suneung and Ijeong founded the temple upon their return from their religious studies in Tang China (618–690, 705–907 A.D.). According to one temple legend, the two monks helped heal the wife of King Aejang of Silla (r. 800 – 809 A.D.). Suneung and Ijeong studied Esoteric Buddhism, or Chongji-jong in Korean, while in Tang China. Purportedly, the wife of King Aejang of Silla had a tumour. The monks tied a piece of silk thread around the tumour and attached it to a neighbouring tree. They then chanted Esoteric Buddhist verses, or jin-eun in Korean, that they had learned in Tang China. Miraculously, and through these Buddhist chants, the tumour vanished, while the tree withered and eventually died. Grateful, King Aejang of Silla (r. 800-809 A.D.) granted the two monks funding that they would need to build a new temple wherever they wanted it. Surprisingly, the two monks chose to construct their new temple in the remote mountainscape of Mt. Gayasan. They would become the first and second abbots of Haeinsa Temple.

Haeinsa Temple also played a pivotal role in the assumption of King Taejo of Goryeo (r. 918-943 A.D.), or Taejo Wang Geon, to the throne. For this, the monk Huirang, who was the fifth abbot of Haeinsa, or Juji in Korean, was rewarded for his loyalty. Huirang, and through him, Haeinsa Temple, received substantial royal patronage from King Taejo of Goryeo. As a result, Haeinsa Temple went from a mid-sized temple to a major temple. This resulted in hundreds of monks being able to study and practice at Haeinsa Temple and the Hwaeom teachings.

Fortunately, Haeinsa Temple has been protected from plundering and destruction because of its remote and isolated location unlike other famous Buddhist temples on the Korean Peninsula. Such was the case in 1592, when the Korean Peninsula was invaded by the Japanese during the Imjin War (1592-1598). In fact, the Japanese intended to cart the woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana back to Japan. However, the monk Seosan-daesa (1520-1604) organized a legion of Buddhist monks known as the Righteous Army to fight in defence of the nation under the leadership of Samyeong-daesa (1544-1610), who was a disciple of Seosan-daesa. This force was stationed out of Haeinsa Temple, and they fought, and won, against the Japanese army by employing guerrilla tactics through the Hongnyu-dong Valley. This victory allowed for the precious Tripitaka Koreana woodblocks to be spared from Japanese plundering.

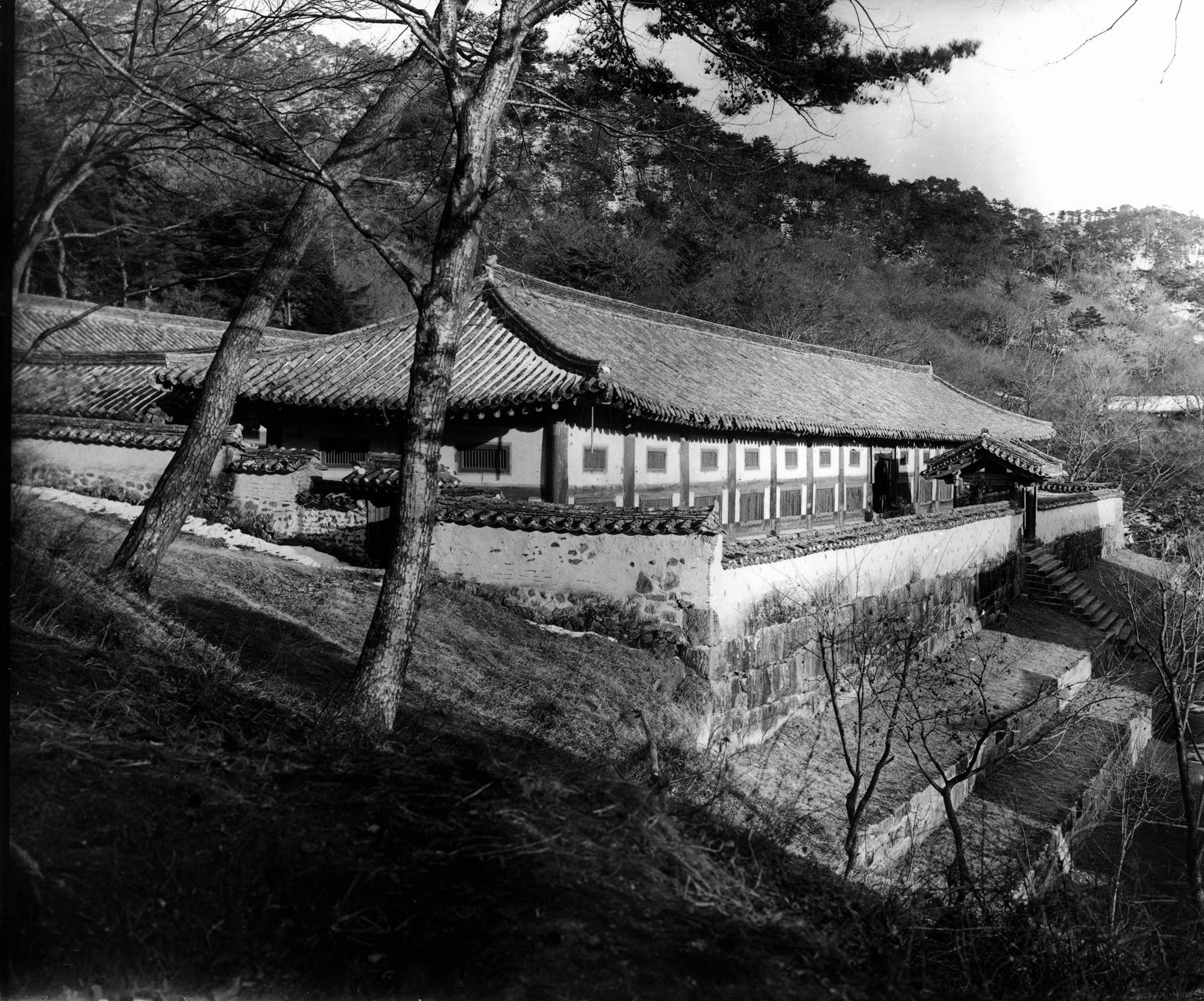

Throughout the centuries, Haeinsa Temple has undergone numerous expansions like in 1488, 1622, and 1644. Tragically, most of Haeinsa Temple was destroyed by fire in 1817. In total, Haeinsa Temple has suffered seven disastrous fires with varying degrees of destruction. Fortunately, the fire of 1817 spared the Janggyeong-panjeon (National Treasure #52) and the Tripitaka Koreana (National Treasure #32) housed inside the ancient library.

Later, and during the Korean War (1950-1953), communist guerrillas attempted to use Haeinsa Temple as their base. However, the abbot of Haeinsa Temple, Master Hyodang, thwarted this attempt, and he was able to convince them to withdraw from the temple grounds. Additionally, the South Korean army didn’t know of this withdrawal, so they ordered airplanes to bomb and destroy Haeinsa Temple. Thankfully, the pilot refused this order and helped preserve Haeinsa Temple.

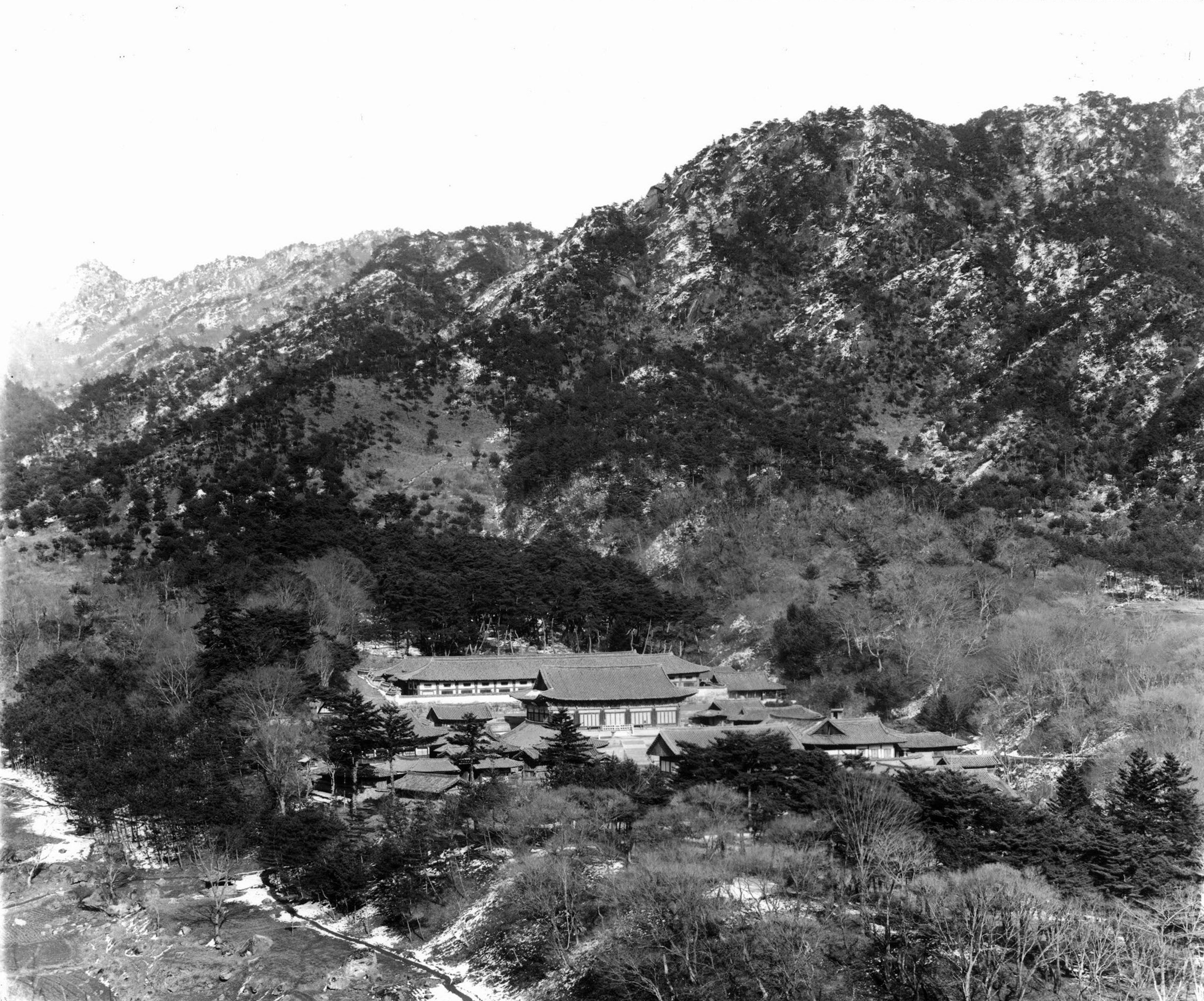

More recently, Haeinsa Temple underwent renovations during the 1960s to 1970s. This was done through funding by President Park Chung-hee (1917-1979). This was meant to help further tourism and rebuild and reestablish pride in Korea. In total, the Haeinsa Temple grounds is home to seventeen hermitages, which is one of the largest collections of hermitages on a temple site in Korea.

Haeinsa Temple is home to four National Treasures, 19 Korean Treasures, the temple itself is a Scenic Site and it’s also a Historic Site. Haeinsa Temple, and more specifically, the Janggyeongpanjeon Depositories of Haeinsa Temple and the Printing Woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana in Haeinsa Temple, have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1995. Additionally, Haeinsa Temple is a popular destination for the Templestay program in Korea.

A special thank you goes out to Prof. David Mason for the amazing information that he provides on his website, especially the history of Haeinsa Temple. Please check it out!

Temple Layout

Haeinsa Temple is located in Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do in a remote valley under the steep slopes of Mt. Gayasan (1,430 m). Additionally, Haeinsa Temple is located in Gayasan National Park, which was established in 1972.

As you first make your way up the trail towards Haeinsa Temple, you’ll be joined by the beautiful Gaya River. The trail and the view are meditative in their beautiful simplicity. The first structure to greet you at Haeinsa Temple is the stately Iljumun Gate. Up a pathway lined with a column of trees on either side, you’ll make your way up to the Cheonwangmun Gate. But before entering the Cheonwangmun Gate, you’ll notice an ancient elm tree that was purportedly planted by a Silla king not long after the founding of Haeinsa Temple. The tree lived for 1,200 years, when it finally died in 1945. However, the rows of trees that grow around it are its descendants. Finally entering the Cheonwangmun Gate, you’ll notice four murals dedicated to the Four Heavenly Kings. These murals are quite expressive.

Now having passed through the Cheonwangmun Gate, but before passing through the Haetalmun Gate, you’ll notice a diminutive shrine hall. This is the Guksa-dang Hall, which houses a mural of a female deity known as Jeonggyun-myeoju. This female deity is believed to be the guardian of Mt. Gayasan. And people can pray to this image inside the Guksa-dang Hall for good fortune. In fact, Jeonggyun-myeoju is believed to be the matriarch of the Gaya Confederacy (42 – 562 A.D.). More specifically, Jeonggyun-myeoju is believed to be the mother of the mythological founder of Daegaya, King Ijinasi. Rather interestingly, this temple shrine hall used to be a Sanshin-gak Hall. However, and during the 1990s, the image of Sanshin was exiled and the hall was converted into a Guksa-dang Hall. As to when the Guksa-dang Hall was first established, it’s unknown; however, it is known that the shrine hall was repaired in 1855, 1899, 1961, and as recently as 2007.

Now having passed through the Haetalmun Gate, you’ll enter into the lower courtyard at Haeinsa Temple. Housed inside this lower courtyard is the Jong-ru Pavilion (Bell Pavilion). Housed inside this pavilion are a beautiful collection of the four traditional percussion instruments including a green, dragon-headed mokeo (wooden fish drum). Before ascending the stairs that make their way around the Gugwan-ru Pavilion that shields the lower courtyard from the upper, have a walk through the temple maze. This maze is created around an ancient stone pagoda, and it’s meant to symbolize the Beopgye-do diagram drawn by Uisang-daesa. This is meant to help practice walking meditation, and it’s a modern addition to the temple.

Having walked around on either side of the large Gugwan-ru Pavilion, you’ll be standing squarely in the upper courtyard at Haeinsa Temple. And the first thing to draw your attention is the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall. Rather interestingly, this temple shrine hall’s central image is that of Birojana-bul (The Buddha of Cosmic Energy). And this central image is joined by five additional main altar statues. This large main hall was first built in 1818, and it was renovated in 2004. The exterior walls of the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall are adorned with Palsang-do (The Eight Scenes from the Historical Buddha’s Life Murals).

Joining the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall in the upper courtyard is the Gwaneum-jeon Hall, which is situated to the right of the main hall. There are two additional temple shrine halls to the right of the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall. They are the Myeongbu-jeon Hall and the Eungjin-jeon Hall. The exterior walls to the Eungjin-jeon Hall are surrounded by the Nahan (The Historical Disciples of the Buddha). Stepping inside the Eungjin-jeon Hall, you’ll find Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Disciple of the Buddha). This central image is joined on either side by sixteen statues of the Nahan, who are backed by murals of these disciples. And next to the Eungjin-jeon Hall is the Myeongbu-jeon Hall, which is dedicated to Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife). The exterior is adorned with simple dancheong colours and floral and animal paintings, as well. Stepping inside the Myeongbu-jeon Hall, you’ll find a green haired image of Jijang-bosal on the main altar, who is joined by statues of the Siwang (The Ten Kings of the Underworld).

To the left of the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall, on the other hand, you’ll find two additional temple shrine halls. They are the Daebiro-jeon Hall and the hexagonal Dokseong-gak Hall. Housed inside the newly built Daebiro-jeon Hall, you’ll find three additional incarnations of Birojana-bul on the main altar. As for the uniquely designed Dokseong-gak Hall, you’ll find a large, peaceful mural dedicated to Dokseong (The Lonely Saint) inside. The image of Dokseong appears under a beautiful cherry blossom tree.

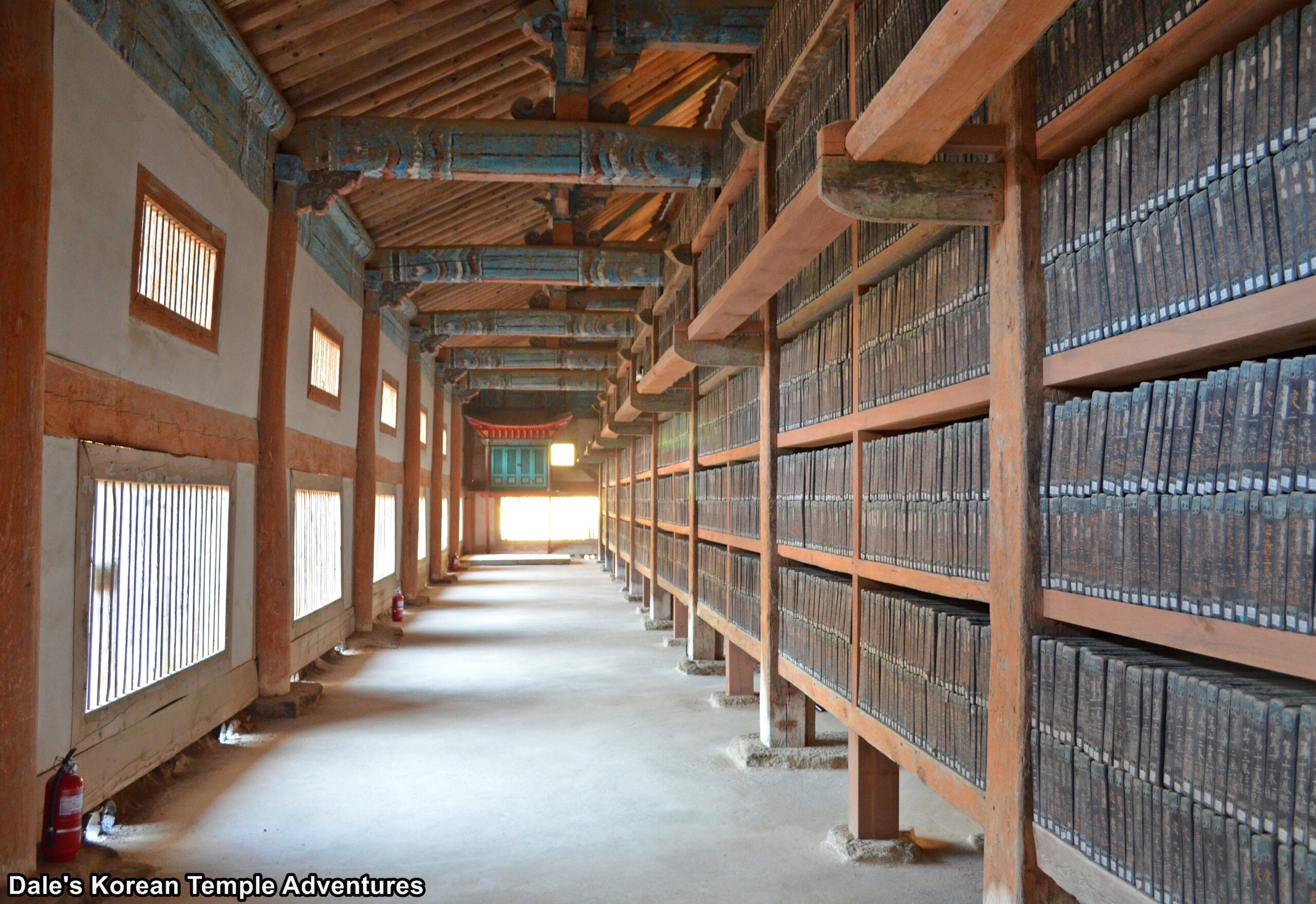

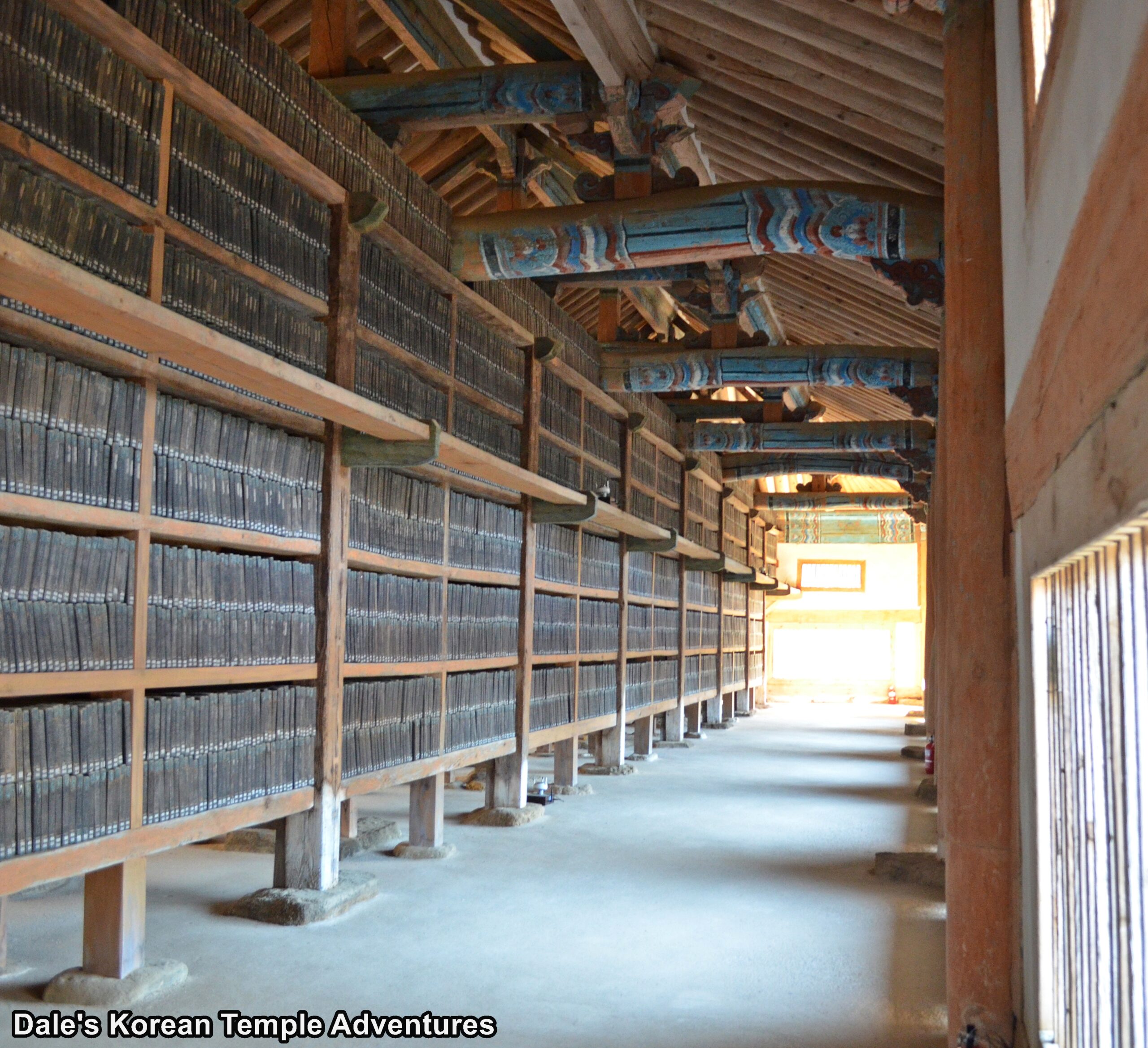

But it’s to the rear of the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall, and up an embankment and a set of stairs, that you find the main highlight to Haeinsa Temple. In this area you’ll find the Printing Woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana of Haeinsa Temple and the Janggyeong-panjeon Depositories of Haeinsa Temple that store these woodblocks. The woodblocks that comprise the Tripitaka Koreana are the most comprehensive and oldest intact collection of Buddhist texts. “Koreana” means Goryeo, while “Tripitaka” are Buddhist texts that mean “three baskets” in Sanskrit. The Tripitaka Koreana are also known as Goryeo Daejanggyeong, or Great Collection of Buddhist Scriptures of Goryeo in English. They are also known as the Palman Daejanggyeong, or Eighty-Thousand Tripitaka in English, since the total number of woodblocks used to print the scriptures came to more than eighty thousand.

The woodblocks were first made in 1087; however, they were later destroyed by the invading Mongol in 1232. To help inspire divine assistance in the defence of the nation, King Gojong of Goryeo (r. 1213-1259) ordered that the set be remade. This second set replaced the first edition that had been made by Uicheon (1055-1101). Over a twelve year period, starting in 1237, the Tripitaka Koreana were completed in 1248. And in 1398, the set was moved to its present home of Haeinsa Temple, where they were stored in the Janggyeong-panjeon. In total, there are 81,258 wooden printing blocks that are without a single error. Each woodblock measures 24 centimetres in height and 70 centimetres in length. Each block weighs between three to four kilograms.

As for the two buildings that the Tripitaka Koreana are housed in, they are known as Janggyeong-panjeon Depositories of Haeinsa Temple. These two buildings are the oldest structures at Haeinsa Temple; however, it’s unclear as to just how old they might be. The Janggyeong-panjeon Depositories underwent a major renovation in 1457, and they were rebuilt in 1488. There were also two additional renovations that took place on the structures in 1622 and 1624. The structure is shaped like a rectangle with the two larger sides standing on the north and south. There is no decoration adorning the Janggyeong-panjeon Depositories. Each depository has two rows of windows with different sizes (one on the front and the other on the back). This is to ensure natural ventilation throughout the depository. And the earthen floor is laid over layers of powered charcoal, lime, salt, and sand. This is meant to effectively control the moisture around the historic Tripitaka Koreana, and it seems to be doing the trick as not one single woodblock has been warped or misshapen by time.

Haeinsa Temple Hermitages

In total, there are 11 hermitages spread throughout the Hainesa Temple grounds. There are some closer to the temple, while others are situated closer to the mountains. Here is a list of those hermitages.

1. Gilsangam Hermitage – 길상암

6. Geumseonam Hermitage – 금선암

How To Get There

From the Seobu Bus Terminal in Daegu, you can get an express bus to Haeinsa Temple. The bus leaves about every 40 minutes, and the bus ride lasts about an hour and a half.

Overall Rating: 10/10

Obviously, the Tripitaka Koreana and the Janggyeong-panjeon Depositories that they’re housed in are the main highlights to Haeinsa Temple. You simply won’t find anything else like it in Korea; let alone, the world, for that matter. Collectively, they are beautiful in their simplicity and spirituality. In addition to this unique highlight, other things to enjoy is the massive Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall, the numerous temple shrine halls, and the scenic beauty that surrounds the ancient temple.