Myeongbu-jeon – The Judgment Hall: 명부전

Introduction

Another prominent figure in Korean Buddhism is Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife). Next to the Gwaneum-jeon Hall, the Myeongbu-jeon Hall is the most popular Bodhisattva shrine hall at a Korean Buddhist temple. At major temples, Jijang-bosal is housed in his own hall, which is called the Myeongbu-jeon Hall, or the “Judgment Hall,” in English. It’s meant to symbolize a “dark court” or “underworld,” where the souls of the dead are being judged. The Judgment Hall is one of the more unique looking buildings at a temple because of its gruesome depictions of the afterlife, the uplifting paintings of salvation, the ominous judges, and the serenely redemptive Jijang-bosal. At smaller temples, Jijang-bosal will often be housed in the main hall alongside other Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in the main triad of statues that sits on the main altar.

Myeongbu-jeon Design

Jijang-bosal is committed to remain on earth until there are no more suffering souls in hell. Jijang-bosal was authorized by Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha) to enlighten all sentient beings by delivering them from the suffering caused during the vast time between the passing of Seokgamoni-bul and the coming of Mireuk-bul (The Future Buddha). Jijang-bosal, in his former life, saved his mother from the underworld through his fervent prayers and pious offerings. Also, he made vows to help relieve people from their sufferings, especially those fated to suffer in the afterlife. In fact, Jijang-bosal is so committed to alleviating the suffering of others that he will even enter the depths of hell to do this. A wonderful mural that depicts this can be found at Sinheungsa Temple in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do. In this mural, the flames of hell, which almost look like lava, are surrounding Jijang-bosal as he stands stoically on a stony outcropping attempting to alleviate the suffering of those individuals in pain and in need of his aid.

The Myeongbu-jeon Hall appears at temples for the dead. The family of the deceased will hold a memorial service for the dead over the course of forty-nine days, at seven-day intervals. On the 49th day, the family holds a “49th Day Memorial Service.” Also, the rate with which a soul passes through the underworld slows, too. The eighth court of the underworld takes 100 days, the ninth will take a year. And an additional three years to get to the tenth underworld court. The whole point of this service is for the family to help guide the spirit of the dead through the afterlife and onto the Buddhist Pure Land, or “Jeongto,” in Korean.

Jijang-bosal is one of the easier Buddhas or Bodhisattvas to identify. In fact, he’s probably the easiest to identify. The best way to identify Jijang-bosal is through his short cropped black or green hair. In his right hand he typically holds a monk’s staff with six rings attached to it at the top. This monk’s staff is used for opening the doors to the afterlife. And in his left hand, Jijang-bosal holds a pearl (or a wish-fulfilling gem). This pearl can do a couple of things. First, it can light up the darkest depths of the afterlife; secondly, it grants wishes to selfless individuals. Jijang-bosal is typically joined on the main altar of the Myeongbu-jeon by Mudokgui-wang (The King of Ghosts Who Purifies People’s Minds) and Master Daoming, who is known as a “Returned Soul,” because he came back from the underworld to help others.

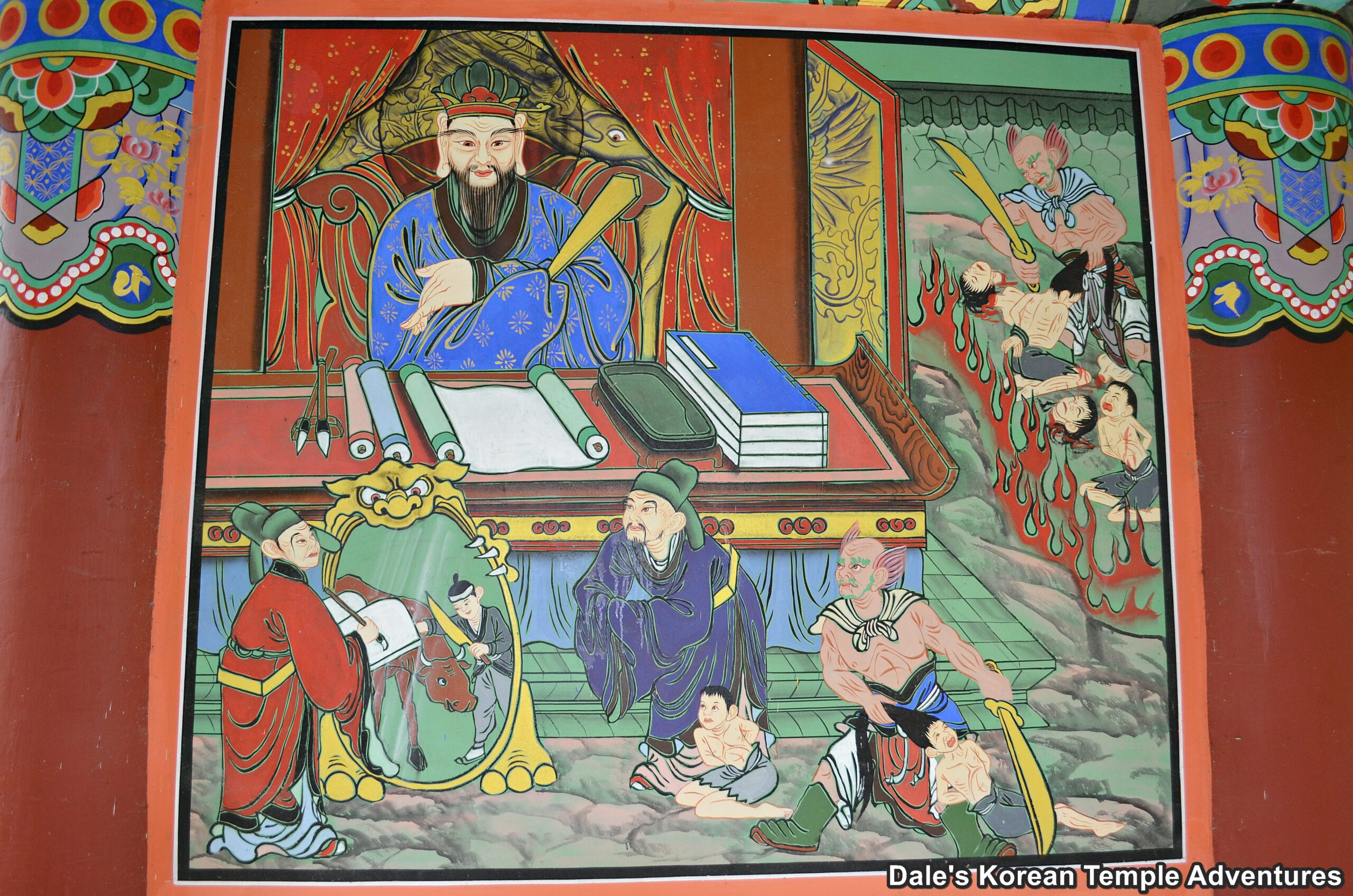

As for the main altar, which houses Jijang-bosal, it’s typically surrounded by the Ten Kings of the Underworld, or “Shiwang,” in Korean. In Buddhism, not all souls that go to the underworld are damned. Instead, each person that dies will first find their way to the proper Underworld courtroom to be judged. A Karma mirror called an “Eopgyeong-dae,” in Korean, is held up to a deceased person and all their good and bad deeds are reflected to their spirit. Paintings of these scenes are a reminder of the consequences of a person’s actions while they live. The categories of judgment for the deceased are murder, lying, corruption, theft, lack of filial piety, failing to help others, and sexual misconduct.

As for the Kings, they are usually statues, and they can either be seated on thrones or standing. Typically, there are five Kings on either side of the altar, respectively. In more elaborate halls, these Ten Kings are joined by attendants. And if the hall is really, really elaborate and ornate, the Ten Kings are backed by murals of the territory each judge governs over in the Underworld. A great example of these can be found at Heungguksa Temple in Yeosu, Jeollanam-do, which are Korean Treasure #1566.

The exterior of a Myeongbu-jeon Hall can be just as, if not more, elaborate than the interior. While typically smaller in stature and understated, the hall more than makes up for it with its artwork. Almost always, this hall is adorned with a gruesome set of grotesque paintings of people being judged and punished in the afterlife. These paintings, as a result of their originality and creativity, can be among the finest at any temple or hermitage. Some great examples of this style of artwork adorning exterior walls of a Myeongbu-jeon Hall can be found at Yongjusa Temple in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do and at Songnimsa Temple in Chilgok, Gyeongsangbuk-do. You can see in the painting people being boiled alive, having their tongues pulled out, bitterly cold, flayed, tormented by poisonous snakes, lying on a bed of metal spikes, impaled, and just generally being tortured by Agwi (Hungry Spirits). The Myeongbu-jeon Halls at these temples are like a Buddhist version of Dante’s Inferno.

Conclusion

So the next time you’re at a Korean Buddhist temple, have a look for the Myeongbu-jeon Hall. This elaborate Judgment hall is amazingly painted, both inside and out, with murals of those suffering in the afterlife, and with those redemptively being saved through the grace of Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife).