Siwang – The Ten Kings of the Underworld: 시왕

Introduction to the Ten Kings of the Underworld

The origins and development of the Ten Kings of the Underworld, which are known as the “Siwang” in Korean, is a lengthy one. The Ten Kings, as we know them today, are solidified around the 9th century in China over a gradual process with numerous influences (both social and religious). Here is their journey through time, culture, and religions.

Pre-Buddhism and Early Buddhism in China

Before Buddhism had entered the Han Dynasty (202 B.C. – 220 A.D.), the descriptions of the afterlife are somewhat vague and simple. Additionally, these descriptions lack detail. Instead, all that the underworld is associated with is with cold and darkness; however, there is no mention of punishments for the dead.

The earliest indications of the existence of an underworld for the dead is found in the concept of the “Yellow Springs” (huangquan), which is a subterranean realm where the spirits of the dead assemble. The origin of this belief dates back to the Spring and Autumn Period in China which dates back to 722 to 481 B.C. A story recounted in the “Zuo Commentary” (Zuozhuan) talks about an official who wishes to see his dead mother. So this official decides to dig a passageway through the earth to get to the “Yellow Springs.” By the early Western Han (206 B.C. – 6 A.D.), the “Yellow Springs” becomes a common and widespread belief in the afterlife in China.

Starting with the Han Dynasty (202 B.C. – 220 A.D.), we start to see tombs being built as imitations of houses. This was an evolutionary change from the former cold, dark view of the afterlife. Instead, the afterlife was viewed as something familiar and something that could be understood by the living. The funerary objects that people were buried with are everyday items that included the possessions of the deceased. Also, we start to see the replacement of these everyday items with clay replacements that are specifically made to represent those everyday objects that people would need in the afterlife. These clay objects, in turn, would be replaced by paper and writing. Additionally, a god, the Yellow Emperor, is now believed to be in charge of the registers of the living and the records of the dead with a whole host of messengers and officers to help aid in these activities.

The physical structure and description of the underworld for the dead still remains obscure at this time at least until the beginning of the Eastern Han (25-200 A.D.). However, as early as the 1st century B.C., a duplicate of the living world is replicated as a subterranean afterlife. This helps to physically separate the living from the dead. Added to this new world for the dead is an extension of the bureaucratic norms found in Han governance, including both civil and military aspects. This bureaucracy in charge of the afterlife was a close, and rather frightening, similar copy of the human world of governance. This, in turn, would help develop and conceptualize the punishments doled out in the afterlife. So by the beginning of the Common Era, we see a complex subterranean world of the dead already taking shape at this time.

As such, and in general terms, the dead was conceived of with the idea of a twin soul (a common belief in China at this time) that separated the po and the hun souls. The spirit of the dead was first identified as the po soul; and only later, would the po soul be joined to the hun soul to form a dual soul in Eastern Zhou. The concept of the double/dual souls would only be further developed during the middle of the Han Dynasty. This would help form new models of understanding about the afterlife.

It was to this, when Buddhism first arrived during the 1st century Common Era, that such ideas of the underworld (and its torments) met fertile ground in China. The ideas of karma and rebirth in Buddhism would meet an unfixed underworld of bureaucracy and torment.

It’s really important to note that the Chinese didn’t have a systematized thought linking the underworld and the afterlife with a moral concept of a system of cause and effect as did the Buddhists. This is especially true concerning the idea of karma, responsibility, sin, and how it involved the span of multiple lifetimes. So that’s why when Buddhism entered China, not only did it introduce a detailed version of the underworld and the afterlife, but it also conceptualized the individual as something different through their role and place in the world.

What’s also interesting, and also a feature of Korean Buddhism and its interaction with Korean shamanism, is the quick adaptation of Buddhism with local traditions and beliefs in China. This can be found during the first half of the third century, in the translated sutra of the “Sumagadhavadana sutra” in 230 A.D., as well as the “Compiled Scriptures on the Six Perfections,” which was translated in 251 A.D. Of note, and from the “Compiled Scriptures on the Six Perfections,” we find the following quote: “After the end of one’s life, the hun soul enters the hells of Mt. Tai, where they are burned and boiled [and subjected to] ten thousand cruelties.”

Found in this quote is the incorporation of Mt. Tai and its god into Buddhist cosmology, specifically with regards to the underworld. Traditionally in China, Mt. Tai was used as a gateway to the underworld and a conflation between the real and the imagined in Chinese Taoism. And in this amalgamation of beliefs, Buddhism opened itself up to change with Chinese indigenous beliefs. However, by taking this adaptive approach, and by becoming more Chinese, the teachings of Buddhism would change, as well, to become its own new kind of Buddhism separate from its Indian origins.

It’s finally at the end of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386–589 A.D.) that we find rebirth in the afterlife. And in particular, we find individuals dealing with the returning of souls from the afterlife. In fact, it becomes a major theme in popular tales at this time. One of the earliest accounts to be found of such afterlife adventures is found in the “Records of Luoyang’s Monasteries” (Luoyang qielan ji) written around 550 A.D. The tale features a story about the Buddhist monk Huiyi who returns from the dead with an account of the court of King Yama and the officials of the underworld. From this story, we learn that King Yama is the only sovereign of the underworld mentioned at this time in history. Also found in this transitional period is an afterlife based upon a Chinese judicial courtroom setting instead of one based on Indian concepts of the afterlife. Through this example, and by mid-6th century, we find a underworld taking shape increasingly more in line with Chinese cultural norms. And the only aspect of its Indian Buddhist roots are found in King Yama (which had already been adopted from into Buddhism from Hinduism).

By the start of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.), we have a combined form of Buddhist-Taoist underworld and afterlife that has become the standard. Probably the most important collection of stories that help proliferate these beliefs in the afterlife is the “Records of Retribution in the Netherworld” (Mingbao ji) by Tang Lin (600-659 A.D.). This text contains a variety of stories about the underworld. Not only does this text reveal the transformation of the afterlife as a Chinese bureaucracy, but it also reveals the extent to which King Yama has changed, as well, from an Indian deity to that of a Chinese judge.

Also helping in the change at this time with the growing centrality of the Ten Kings and the underworld is the new belief in Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife). While Jijang-bosal appears relatively early on in Buddhist scriptures translated into Chinese, Jijang-bosal is one among a group of eight Great Bodhisattvas. However, towards the end of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386–589 A.D.), the importance of Jijang-bosal and the afterlife dramatically changes. In the following centuries, Jijang-bosal would become a major Buddhist figure in China similar to that of Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion). And both would compete to become the primary savior to those reborn in the underworld.

Textually, the first Buddhist writing to focus on Jijang-bosal is the “Dasacakraksitigarbha sutra,” which is perhaps better known as the “Mahayana Great Collection of the Ten Wheels Scripture of Ksitigarbha.” This text was translated in China by an unknown author during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386–589 A.D.). And it was later expanded from nine rolls into ten rolls from the mid-7th century. And while this text has Jijang-bosal as its central hero, it doesn’t concern itself overly with the afterlife and the underworld. This helps us better understand the evolution of Jijang-bosal at this time. At this time, Jijang-bosal had yet to become the main liberator of souls from torment in the underworld. Over time, this would change.

But perhaps the most significant text in the evolution and growth of Jijang-bosal and the afterlife in China at this time is found in the “Scripture on the Original Vows of the Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha.” The scripture doesn’t include the Ten Kings; however, it does have a series of twenty demon-kings, who are attendants to King Yama. We also find a detailed version of the staff present in the bureaucratic Chinese Buddhist underworld at this time, as well, which will become integral to future ideas of the afterlife. And while this scripture lacks in detail, it definitely instills the idea of fear by those committing bad karma. Specifically, the text includes acts of bad karma that include a lack of filial piety, the cultivation of good morals, and the transference of merit (relatives of the dead can perform good deeds on the dead’s behalf through ritual transfer which aids in their salvation).

Perhaps what’s most significant about this text is that the Ten Kings still aren’t mentioned in an otherwise exhaustive list of deities and spirits contained in the “Scripture on the Original Vows of the Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha.” This is yet another strong indication that the Ten Kings had yet to be fixed as a group to judge the dead by the first quarter of the 8th century. But what we do see at this time is a convergence and development of both the Ten Kings and Jijang-bosal into what we will come to expect in the Chinese Buddhist bureaucratic afterlife.

The Early Ten Kings of the Underworld in China

The earliest reference to the Ten Kings is in a work that catalogues Buddhist texts and provides brief bios of their authors. This text was compiled by Tao-hsuan (596-667 A.D.) in 664 A.D. Tao-hsuan records the names of two treatises written by a monk named Fa-yun, who was active in Chang-an in the mid-7th century. Fa-yun’s “Essay on the True Karma of the Ten Kings” was still in existence in the 11th century, but wasn’t preserved after that. It’s believed to have been written as a prose essay, and it explained the operation of karmic retribution perhaps even devoting one chapter to each evil action punished in the ten courts.

All Ten Kings are mentioned by name for the first time in surviving sources in “The Scripture on the Ten Kings.” This sutra is also known as “The Scripture Spoken by the Buddha to the Four Orders on the Prophecy Given to King Yama Concerning the Sevens of Life to Be Cultivated in Preparation for Rebirth in the Pure Land.” The name of the text was also shortened to that of “The Scripture on the Prophecy Given to King Yama.” Or more simply, “The Scripture on the Ten Kings.”

The name of the scripture’s author is a monk named Tsang-ch’uan, who lived at Ta-sheng-tz’u ssu in Ch’eng-tu. The earliest datable copy of the sutra dates back to 908 A.D. It was presumably copied from a master version kept at one of the 18 temples in the garrison town of Dunhuang in Sha-chou, but where that original text came from is still unknown.

However, what is known, or at least believed, is that “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” probably didn’t exist in the year 720 A.D. when the monk Chih-sheng (fl. 669-740 A.D.) defined what would become the core of all later canons in his “Catalogue of Items of the Buddhist Teaching Compiled” during the K’ai-yuan Era. It’s likely that the text was put together sometime between 720-908 A.D. So it’s at this time that we get a fully named and fleshed-out idea of the Ten Kings of the Underworld.

In this text, Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha) announces that the very same figure most widely feared for his consistency in giving out punishments in the underworld, King Yama, will be a fully enlightened being, a Buddha, named Bohyeon-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Wisdom) in a future lifetime. It’s also stated in this text by Seokgamoni-bul that those serving in the underworld are serving a higher purpose. Despite these officers meting out punishments, the Ten Kings are actually agents of compassion. In turn, the Ten Kings vow to Seokgamoni-bul to be lenient in their treatment of sinners. Later in the same text, the scripture reinforces the less compassionate side of the Ten Kings by reviewing their titles and the punishment that prisoners will need to endure in each court. Only then does the text detail the journey that a soul goes through from beginning to end through the three years and later rebirth.

The Ten Kings of the Underworld’s Appearance

The cycle with which a soul passes through the underworld is at a rate of seven days for the first seven kings. It then slows down to 100 days for the eighth king; one year for the ninth king; and three years for the tenth and final king before a soul is reincarnated into the next life. The timing of “seven-seven” rites derives from Buddhism; in Tibet, the same stretch is described in the “Bardo Thodol,” or “The Tibetan Book of the Dead” in English.

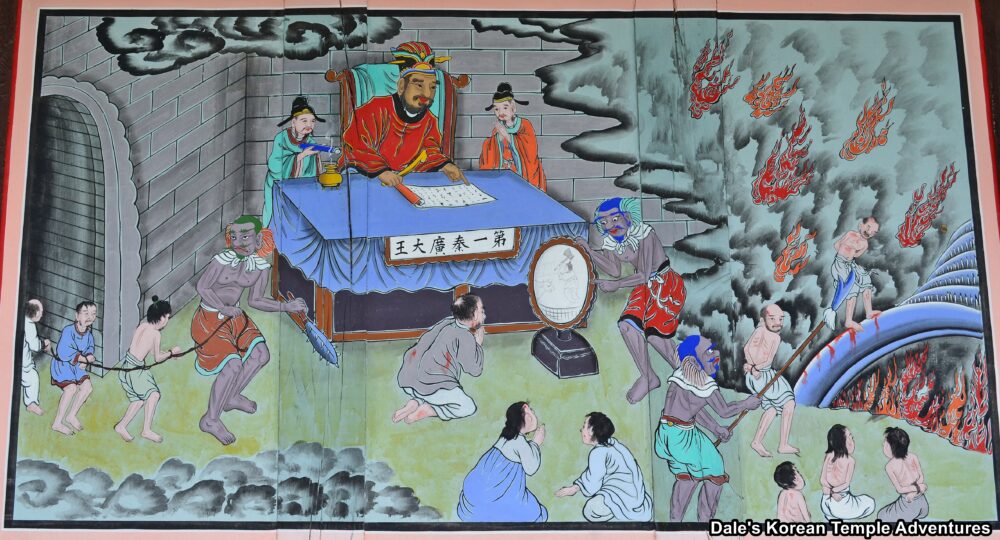

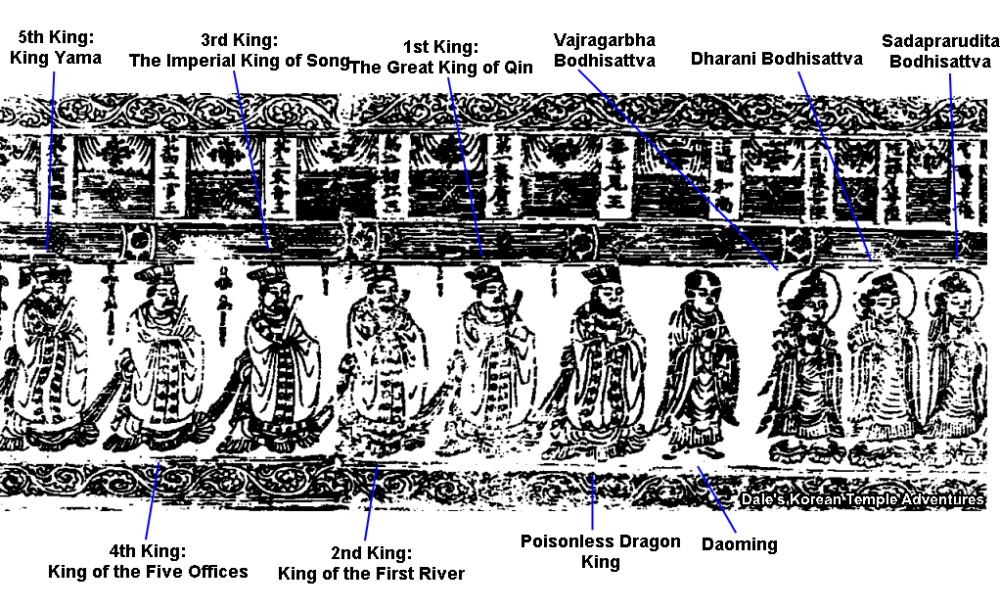

The first of the Ten Kings is “Taegwang – 태광” in Korean (Qin’guang wang – 泰光). The first king, like the third king, has its first Chinese character mean a place name, while the second character is a personal name. In combination, the name means “The Great/Extensive King of Qin” in English. Qin was the name of a Chinese state as early as the Western Zhou Dynasty (1045 BC – 771 BC). Typically, King Taegwang appears seated behind a desk on which papers are stacked. With his right hand, he signals to the two clerks in front of him. To the side can stand the “Boys of Good and Evil.” Sinners will stand before King Taegwang and stooping out of fear and respect. And at the bottom right stands a virtuous woman carrying her donation of a scroll. King Taegwang presides over a soul after its seventh day in the underworld.

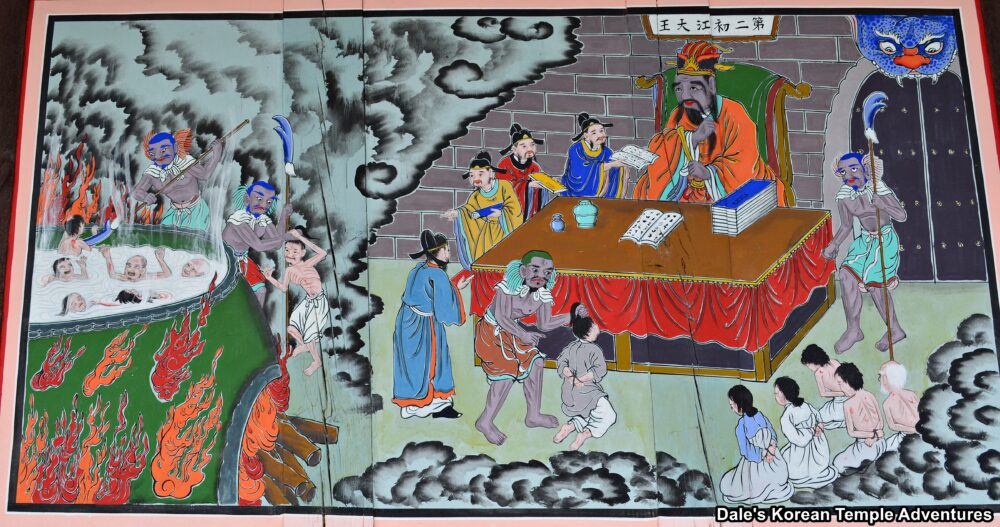

The second of the Ten Kings is “Chogang – 초강” in Korean (Chujiang wang – 初江). The second king means “King of the First River” in English. King Chogang presides over a spirit after 14 days in the underworld. In the second court of the underworld, the dead have no hope of escape. Using the Nai River (Nai-ho), rivers were found in several ancient Chinese accounts of the afterlife. Building upon this indigenous belief, the Nai River is employed to create a familiar description of the afterlife. Typically a cangue has been placed around the necks of those making the journey. Additionally, they find themselves cut off from the rest of the world by mountains. Traditionally, and in Buddhist teachings, mountains were thought to separate humans from the underworld.

The third of the Ten Kings is known as “Songje – 송제” in Korean (Songdi wang – 宋帝). The third king doesn’t appear in earlier source material. And like the first king, the name of the third king is named after a place. “Song” was the name of a Zhou Dynasty state, while “di” literally means “Imperial.” So in English, the name of the third king is “The Imperial King of Song.” The Imperial King of Song presides over the dead after 21 days in the underworld.

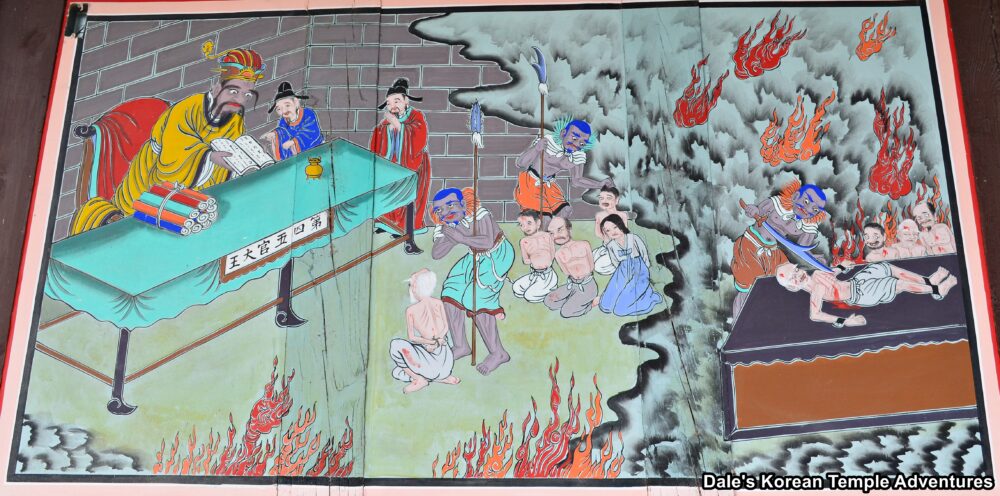

As for the fourth king, he is known as “Oguan – 오관” in Korean (Wuguan wang – 五官). The name of the fourth king literally means “King of the Five Offices” in English. This king appears before the dead after 28 days in the underworld. This king appears as a standard member of the bureaucracy of several indigenous Chinese Buddhist scriptures dating back to the 5th century. One of these texts states that King Oguan ranks just below King Yama. Additionally, King Oguan collects and collates all of the reports of evil actions by spirits and sends them off to lower-ranking officials. As for the reference to the “five offices,” it’s a reference to the five-senses, which can be found in both Indian Buddhist sources, as well as, indigenous Chinese sources.

King Oguan typically appears with sinners shown begging for mercy. These sinners appear with a donor carrying a scroll. Other variations of this king include Karma Scales, known as “yecheng” in Chinese, being used. Here a scroll of a person’s sins are weighed against their good acts as a counterbalance. And the “Boys of Good and Evil” wait to see which side of the Karma Scale will tip upwards (good or evil karma). These Karma Scales are also associated with King Yama. One tale found in the Tang compilation “Widely Praising the Transmission of the Lotus Sutra” (Hongzan Fahua zhuan), recounts how the dead appearing before King Yama would have their karma weighed against two volumes of the “Saddharmapundarika sutra.”

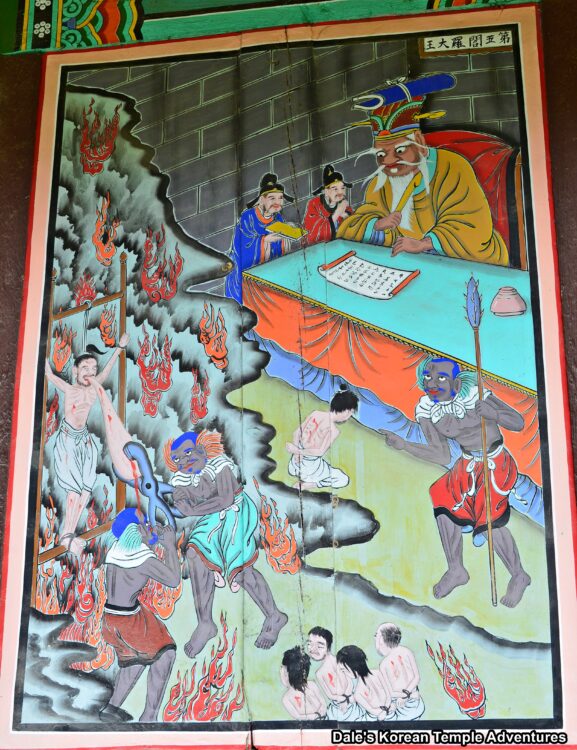

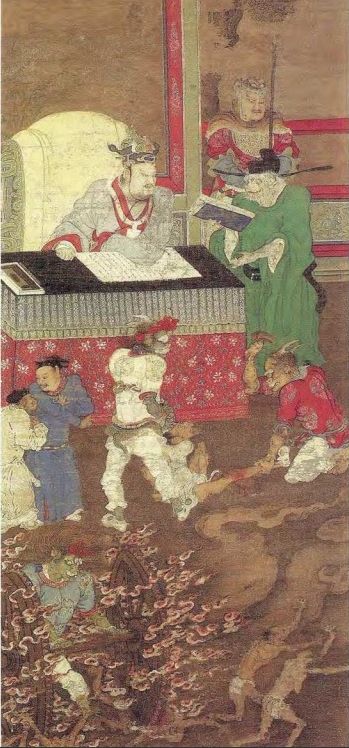

The fifth of the Ten Kings is “Yeomra – 염라” in Korean (Yanluo wang – 閻羅). King Yama, for which this king is better known in English, can trace its origins to the start of Indo-European civilization. Here he appears with a twin sister. In the earliest of hymns for which he appears, King Yama is a benign god who cares for the dead. In Indian Buddhism, King Yama appears as a judge of the dead. Early on, several Chinese translations of the Indian texts attempt to explain King Yama’s ambiguous status as both an exalted king and as a low-ranking being (since he too suffers in the underworld). Of the Ten Kings, King Yama is the highest ranking. He is often referred to as a “Son of Heaven” (Tien tzu). King Yama typically wears a serious bearing and a hat with jade pieces suspended from silk strings (shown sometimes decorated with the Northern Star), which is all appropriate for the rank of an emperor. King Yama appears before the dead after 35 days in the underworld.

Another tool of justice employed by King Yama is the Karma Mirror, which displays the sinner and their karma from their previous life. In “The Scripture on the Ten Kings,” it’s referred to directly as the “Mirror of Karma.” In Chinese, this is known as the “yejing,” while in Korean it’s known as the “eopgyeong.” Originally, the Karma Mirror might have been a precious object of the gods inhabiting the Buddhist heavens. It might also have been a precious object in Indra’s possession, where the karma of all the gods could be seen. In the context of the Buddhist underworld, it’s described in one text as follows: “In the hall inside the court of the Wise King [Guangming wang; namely, King Yama], there is a great mirror on a stand. The mirror of the Wise King is called, ‘Mirror of Purity, Rejecting Partiality.'”

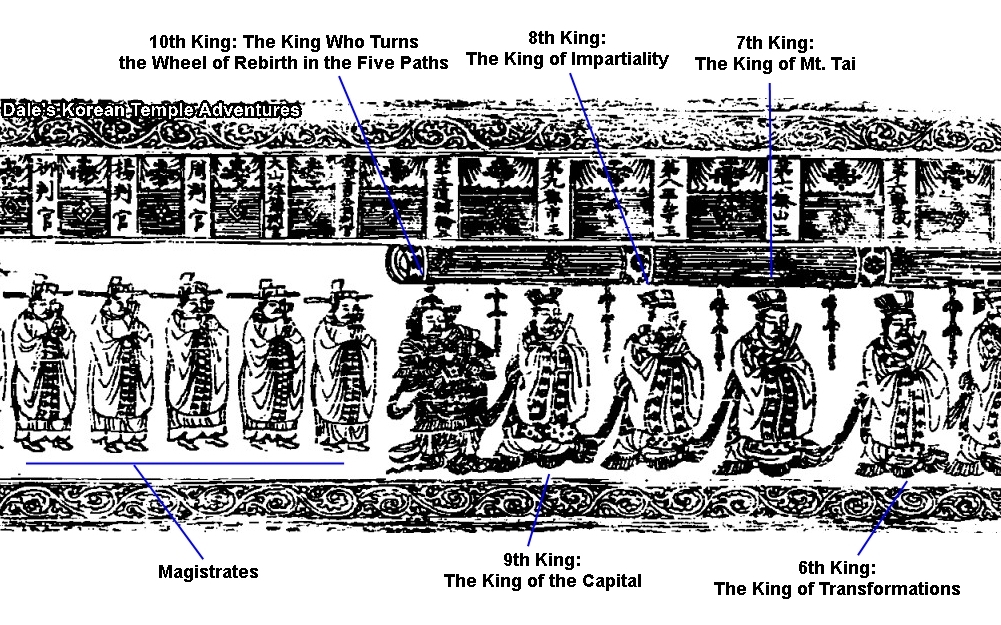

The sixth king is “Byeonseong – 변성” in Korean (Biancheng wang – 變成), or the “King of Transformations” in English. King Byeonsong appears before the dead after 42 days in the underworld. The name of this king might be based upon a description of the underworld from the 5th century. Tales collected by Wang Yuan (424-479 A.D.) detail a journey to the dark regions as the “city where people receive transformed shapes.” Those sent there after death are turned into various animals based upon their karma.

The seventh king of the Ten Kings is “Taesan – 태산” in Korean (Taishan wang – 泰山). In English, the seventh king’s name is “King of Mt. Tai.” The King of Tai presides over the passage of the dead at 49 days. The King of Tai is Chinese in origin, since Mt. Tai (in modern Shantung) was recognized as the seat of the administration of the dead since before the Han Dynasty. The register of life and death was believed to be kept there, and the po and hun souls (the double souls of an individual), were gathered there after death. With the translation of Buddhist sutras into Chinese beginning in the 1st centuries of the Common Era, Mt. Tai was often used to translate and replace the Sanskrit for the Buddhist underworld (Naraka).

The eighth king of the Ten Kings is “Pyeongdeung – 평등” in Korean (Pingdeng wang – 平等). King Pyeongdeung’s court marks the 100th day journey of the dead. In English, this king is known as the “King of Impartiality.” Ancient sources give this king a number of identities. However, the most likely source of this king’s name is based upon an epithet for King Yama; namely, the “Impartial One.” In Tantric texts, they identify King Pyeongdeung as a manifestation of Jijang-bosal, while Manichaean texts from the same time period identifies this king as one of twelve underworld judges. However, and especially according to “The Scripture on the Ten Kings,” King Pyeongdeung acts as an independent figure included as one of the Ten Kings of the Underworld. Typically, the courtroom of King Pyeongdeung will have two donors carrying a banner and a statue. A clerk unrolls his records and sinners are being led by the hair towards the king. Other versions of this courtroom include a sinner wearing a cangue from which heavy metal balls hang. Typically a cangue, which is known as a “chien” in China, is a classical device used for restraining criminals, animals, and slaves.

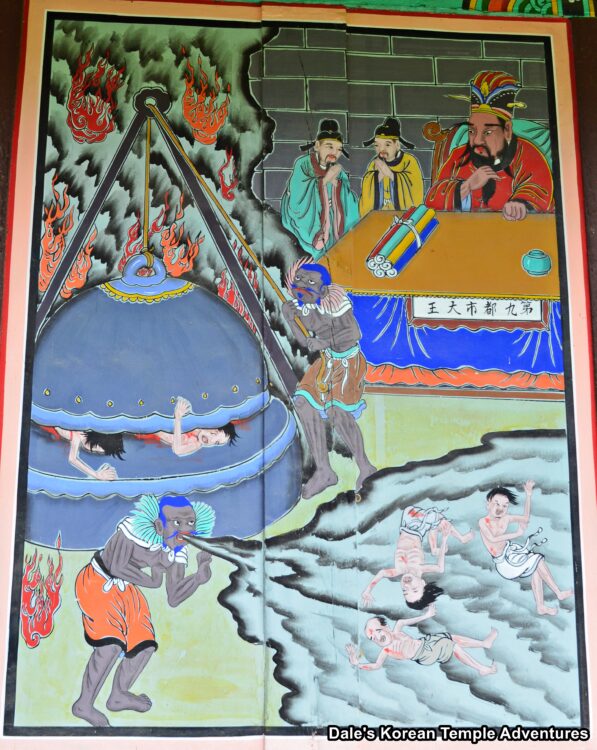

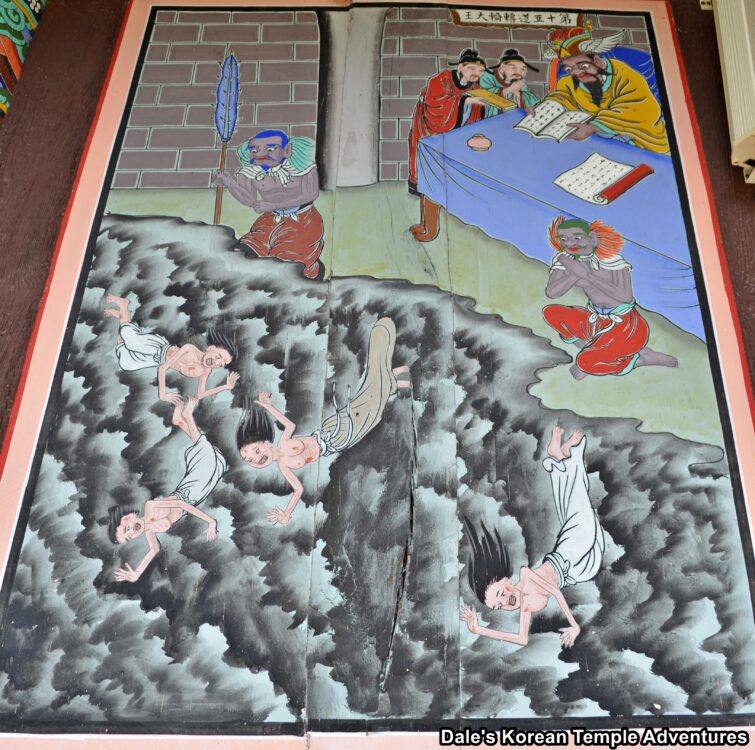

The ninth king of the Ten Kings is “Dosi – 도시” in Korean (Dushi wang – 都市), who presides over the one year mark in a soul’s journey through the underworld. In English, this king is known as “The King of the Capital,” or “The King of the Market of the Capital.” It’s been suggested that the marketplace of a city capital was the natural location for a prison, since markets were the site for public executions. However, it’s probably more likely that this king was based upon older names for underworld officials that included the word “capital” (tu) in their title. One fifth century Chinese Buddhist text refers to this king as “Tu-yang wang” and “Tu-kuan wang.” In this courtroom, a sinner is typically freed from their cangue/shackles. And they clasp their hands out of respect for the king before them. Two donors stand in the top of the painting. There are plumes of clouds which are an allusion to the six paths. However, it’s only from the tenth (and final) courtroom that the six paths are possible.

And the tenth, and final king, of the Ten Kings is “Odojeonryun – 오도전륜” in Korean (Wudao Zhuanlun wang – 五道轉輪), or “The King Who Turns the Wheel of Rebirth in the Five Paths” in English, who presides over the dead after three years. After this court, the dead are assigned to their next mode of life. The clouded pathway shows the five (sometimes six) paths of rebirth in Buddhism. Other versions of this courtroom portray the paths more clearly using symbols to indicate gods, asuras, humans, beasts, hungry ghosts (agwi), and sufferers in hell. Some of these courtrooms also include animal skins to the left of the king. It’s assumed that the king’s assistants would clothe a sinner with the hide appropriate for a soul’s rebirth. As for The King Who Turns the Wheel of Rebirth in the Five Paths, he wears a military suit and a general’s hat. He breathes fire, and he accompanied by assistants and club-wielding demons. This king sends the dead back into the world of the living, which is an attempt to bring the narrative of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” full circle.

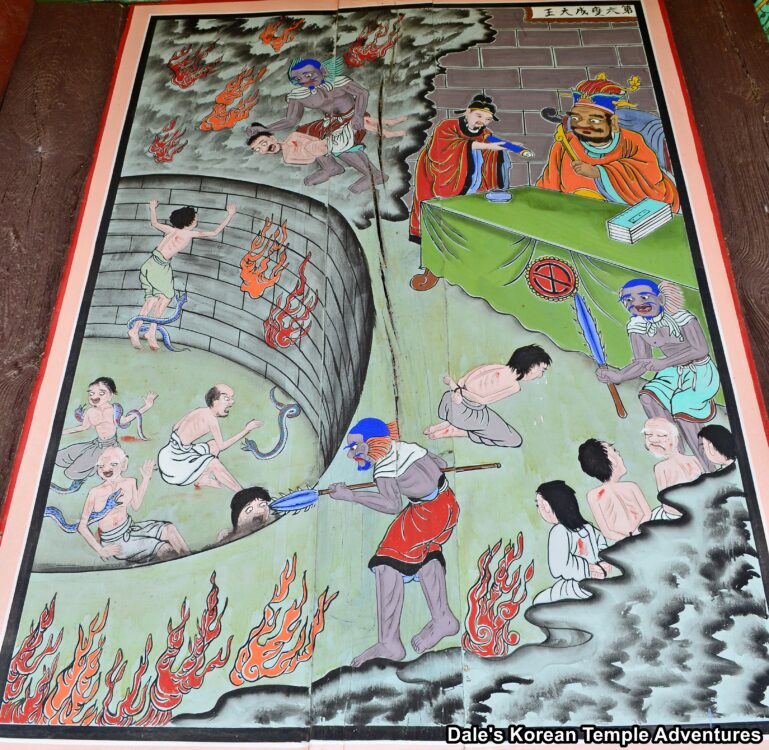

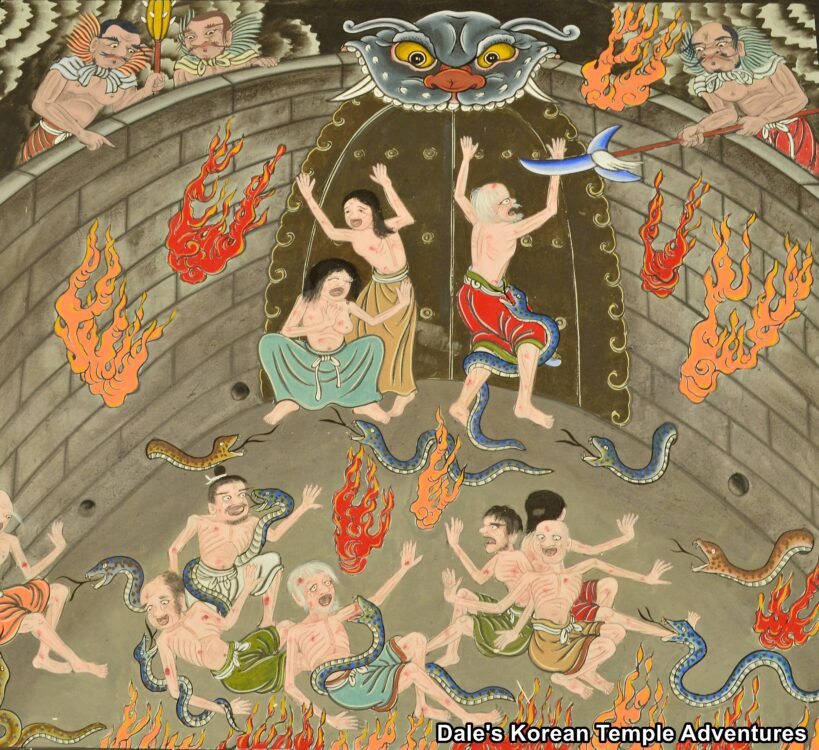

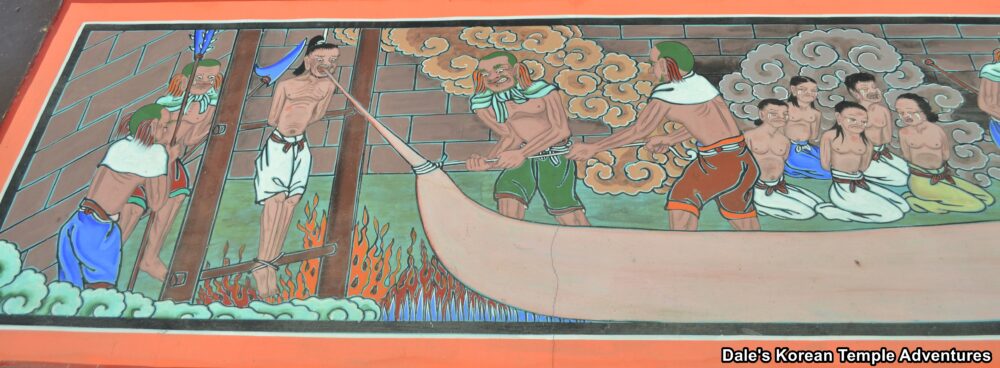

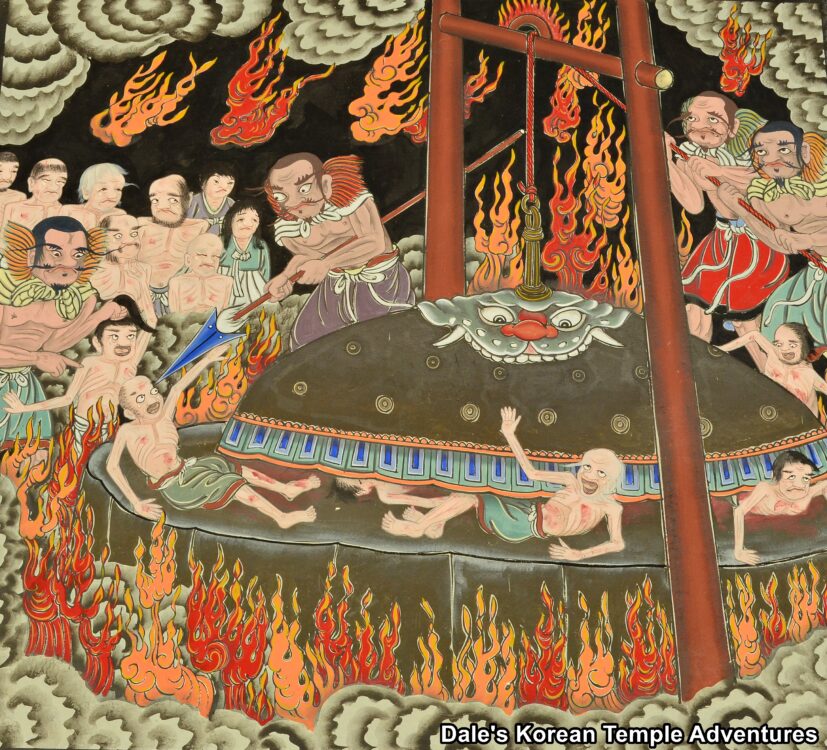

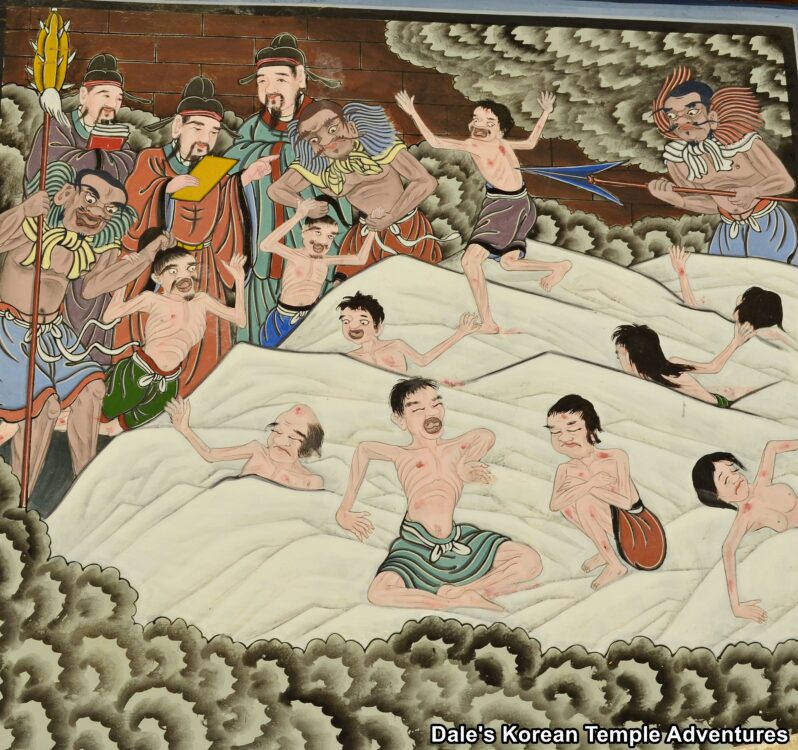

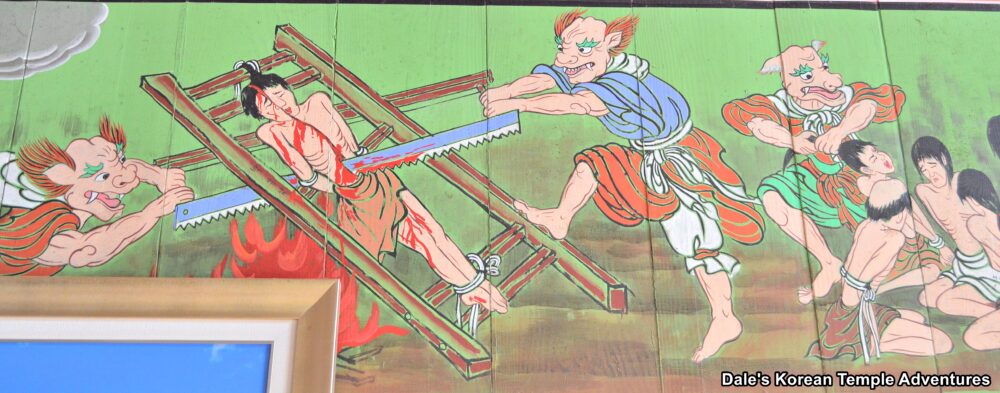

Buddhist Hells

Now, as for the hells that these Ten Kings can send sinners to, they play a prominent role in Korean Buddhist artwork as a deterrent, especially around the exterior walls of the Myeongbu-jeon Hall for which Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife) and the Siwang (The Ten Kings of the Underworld) take up residence. In Sanskrit, this hell is known as “Naraka.” And in Korean, this hell is known as “Jiok – 지옥.”

The traditional view of Naraka in Buddhism is closer to that of a purgatory than it is to a hell. The main reason for this is that there is no divine punishment; instead, it’s one’s accumulated karma that results in one’s punishment. And secondly, the length that one is punished, while it can be for an extremely long period of time, isn’t forever. After this finite amount of time and karma is used up, the individual will be reborn in one of the higher underworlds.

“Diyu” in Chinese, or “Jiok” in Korean, on the other hand, is based upon the idea of traditional Naraka, which is an underground maze with various underworld levels and chambers. This is the place where the dead are brought to to atone for their sins/karma, while they were alive.

Diyu is thought to vaguely resemble Naraka. It consists of several levels; but instead of consisting of the four to one thousand levels found in Indian Buddhism, Diyu consists of four to eighteen levels. More specifically, during the Tang Dynasty, the description of Diyu changed to 134 hells with 18 levels of pain and torture. The concept of the 134 worlds of hell come from the Buddhist text “Sutra on Questions about Hell.” This was later simplified to eighteen levels of hell in the “Sutra on the Eighteen Hells” for convenience. And it’s these 18 hells that make appearances as punishments either independently or incorporated into the murals on the Ten Kings of the Underworld in Korean artwork. According to the “Journey to the West,” here are those 18 punishments in hell:

1. Hell of Hanging Bars

2. Hell of the Wrongful Dead

3. Hell of the Pit of Fire

4. Fengdu Hell

5. Hell of Tongue Ripping

6. Hell of Skinning

7. Hell of Grinding

8. Hell of Pounding

9. Hell of Dismemberment by Vehicles

10. Hell of Ice

11. Hell of Molting

12. Hell of Dismemberment

13. Hell of Oil Cauldrons

14. Hell of Darkness

15. Hell of the Mountain of Knives

16. Hell of the Pool of Blood

17. Avici Hell

18. Hell of Weighing Scales

But they can also include in different textual versions “Hell of Scissors,” “Hell of Trees of Knives,” “Hell of Mirrors of Retribution,” “Hell of Steaming,” “Hell of Copper Pillars,” “Hell of the Mountain of Ice,” “Hell of the Pit of Cattle,” “Hell of Boulder Crushing,” “Hell of Mortars and Pestles,” “Hell of Mills,” “Hell of Sawing,” “Hell of Boiling Sand,” “Hell of Boiling Feces,” “Hell of Darkened Bodies,” “Hell of Fiery Chariots,” “Hell of Iron Beds,” “Hell of Beasts,” and the “Hell of Maggots.” However, the common denominator behind all of these hells is pain, suffering and torture for the sinner.

And of these hells, Korea, for whatever reason, tends to only illustrate about ten to twelve of these various hells. The more common hells that Korean temples tend to illustrate are typically around the exterior walls of the Myeongbu-jeon Hall. And they are “Hell of the Pit of Fire,” “Hell of Tongue Ripping,” “Hell of Grinding,” “Hell of Ice,” “Hell of Dismemberment,” “Hell of Oil Cauldrons,” “Hell of Darkness,” “Hell of the Pool of Blood,” “Hell of Scissors,” and the “Hell of Sawing.” Here are some examples of these paintings from various temples throughout Korea.

The Later Ten Kings of the Underworld in China

The Ten Kings are systematized and finalized as we know them today in the 9th century. And as a subject, they were painted by the 10th century in a variety of ways and locations. Geographically, the Ten Kings could be found in China across most of the northwestern, northern, central, and eastern parts of China by the 9th and 10th century. Rituals, texts, and paintings are found in modern Kansu; prayers and paintings in Shansi; a text in Shantung; statues in Szechwan; paintings in Honan; statues in Anhwei; and paintings in Chekiang. The only place they were not found was in the south (but this might be due more to environmental reasons than social reasons).

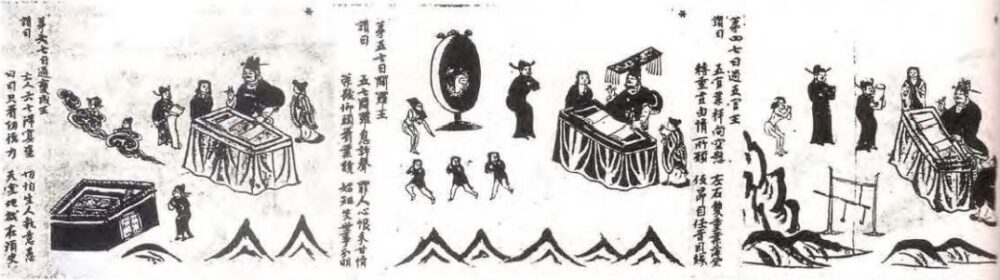

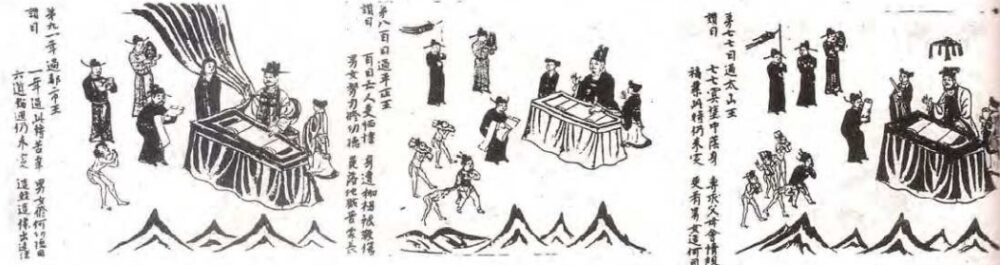

More specifically, and for which there are the most extant examples, there were handscrolls and large hanging paintings also produced at this time. In total, there are 8 examples of handscroll illustrations of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” and 12 hanging scrolls of “Ksitigarbha and the Ten Kings” that exist among the Dunhuang. The handscroll illustrations show the Ten Kings in successive order presiding over individual courts, while the hanging scrolls depict the Ten Kings flanking a central image of Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife) within a single painting.

The handscroll illustration motifs are similar with each other only with slight variations within the group. The large hanging paintings, on the other hand, of Jijang-bosal and the Ten Kings depict the Siwang all in one picture with Jijang-bosal in the centre and flanked by five kings on either side. Unlike the handscrolls, the large hanging paintings rarely show torture scenes. Additionally, the large hanging paintings don’t show a sequence of the soul passing through the courts of the Ten Kings. This style of painting lacks a narrative.

With all this in mind, these two styles of paintings can be divided into “iconic” and “narrative” paintings. With the iconic being the large hanging paintings and the handscrolls being the narrative. As a result, these two styles of paintings served two different functions. As such, they are rendered and presented differently artistically.

Unfortunately, during the 10th century, no art has survived from this period. However, we do know, based on written sources, that there were several artists in the Five Dynasties (907-960 A.D.) who painted the Ten Kings. These artists include Zhang Tu (fl. 907-922), who apparently painted several murals in the temples of Luoyang, while Wang Qiaoshi (fl. 907-960) reportedly painted over 100 versions and images of Jijang-bosal and the Ten Kings. Also, the Japanese monk Jojin (1011-1081), who traveled to China in 1072, reported to have seen statues of the Ten Kings and Jijang-bosal. However, none of the these statues or paintings still exists to this day. But by the 12th century, the Ten Kings were easily recognizable throughout China.

The next major surviving collection of the Ten Kings paintings are from an artist named Jin Chushi and Lu Xinzhong, who were artists who managed large workshops in Ningbo in Southern Song (1127–1279). These artists works were transported in large quantities to Japan during the Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1333-1573) periods.

These paintings, which are two to three hundred years newer than the aforementioned paintings, are markedly different visually from the Dunhuang paintings. In these paintings, there are now ten courts in ten different hanging scrolls. Also, their iconographic similarities to the 10th century are missing, as well. These large paintings would be hung on walls in a hall dedicated to the Ten Kings (five paintings on either side of Jijang-bosal). In these paintings, things like the Nai River, the Scales of Karma, and the six paths of rebirth are eliminated. In their place are secular images of torture and torture devices, as well as outdoor palace settings.

The Ten Kings of the Underworld of Korea

And it’s to this tradition and this belief system in the Siwang (The Ten Kings of the Underworld) that entered the Korean Peninsula by at least the end of the tenth century, if not earlier. “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” was being circulated in the northwest regions of China by the 10th century, and the practices associated with them were being practiced in Korea by the royal members of the court by the end of the 10th or early 11th centuries. So it’s most likely that copies of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” were circulating in Goryeo at least by the 11th century.

And there are several examples from historic records, most notably the Goryeosa, that lends credence to this belief. For example, the Goryeosa indicates that Kim Chiyang (?-1009), a maternal relative of Queen Mother Hwangbo, built the Ten Kings Temple, Siwangsa Temple, on the northwestern corner of the palace grounds. Yet another example from the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), and the Goryeosa, has King Sukjong of Goryeo (r. 1095-1105) visiting Heungboksa Temple to congratulate and honour the erection of the Hall of Ten Kings in 1102. This is only further reinforced when King Injong of Goryeo (r. 1122-1146) purportedly offered prayers at the previously mentioned Ten Kings Temple, Siwangsa Temple, in 1146. All three cases point to the acceptance and spread of the Siwang belief system by the 11th century.

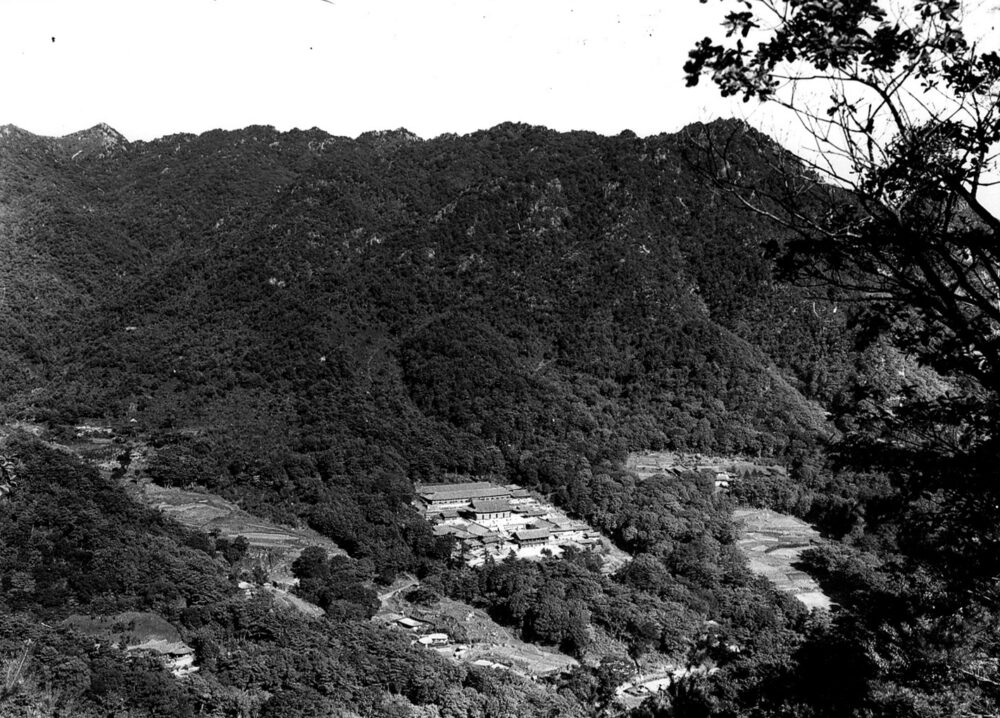

While these three examples clearly indicate that the Ten Kings belief was fully in place by the court during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), no other firm archaeological evidence survives from this time period. That’s why the Tripitaka Koreana from 1246 at Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do is so important.

The Ten Kings of the Underworld at Haeinsa Temple

“The Scripture on the Ten Kings” at Haeinsa Temple aren’t part of the main body of the official Tripitaka Koreana; instead, they are a supplemental sutra commissioned by Cheong-an. Cheong-an was a wealthy and powerful person in the southern province. In the inscription added to this sutra, the text reads:

“For my ancestors and legitimate lineage and their deceased family members, I pray that they all reach the Dharma Realm, and that as sentient beings they do not stagnate in the dark roads, and that they be reborn in the spiritual path in the future in accordance with their vows. These [words] spoken to be carved on printing block for the land of all Buddhas, in the third month of the year byeong-o (1246).”

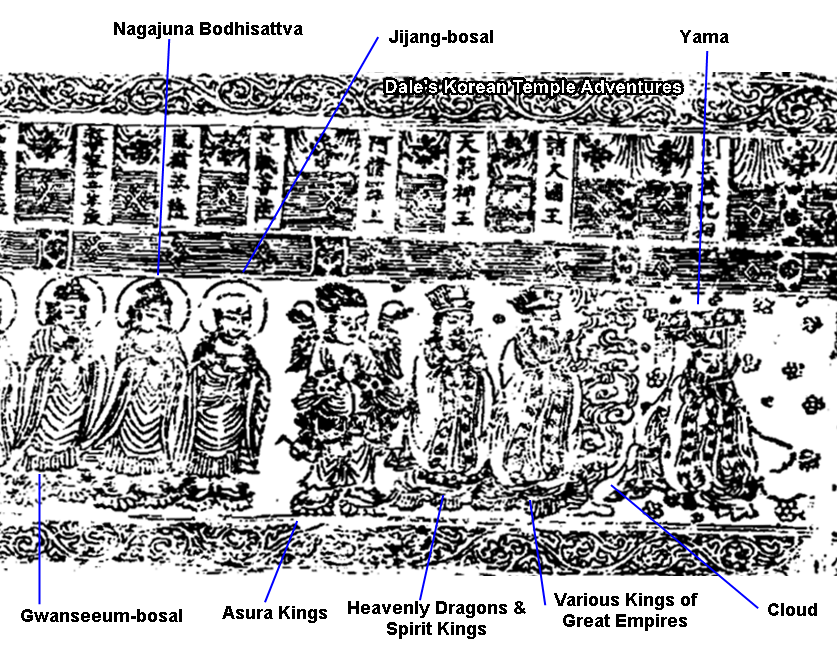

The Haeinsa Temple edition of the “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” added to the Tripitaka Koreana, which is a distinctly Korean piece of work different from other historic Chinese texts. In this Haeinsa Temple edition, the underworld is overpopulated with officials in the afterlife. These officials include, rather obviously, the Ten Kings of the Underworld, as well as asura kings, various kings of great empires, heavenly dragons, spirit kings, an extensive list of demon-kings, magistrates, generals, the Boys of Good and Evil, as was as Daoming, messengers, and various other officials of the underworld.

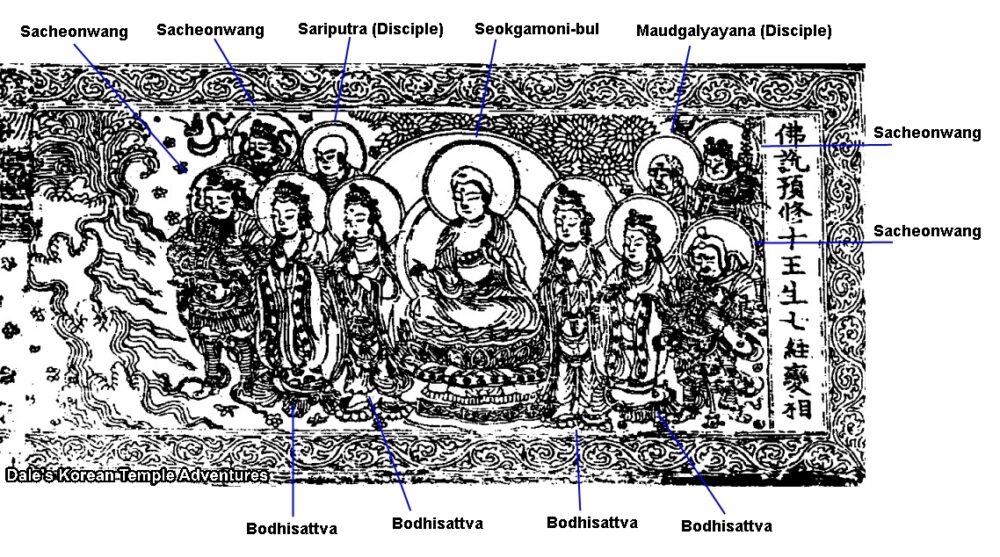

The first plate from the Haeinsa Temple edition of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” is fronted by the Buddha, Seokgamoni-bul. The next plate is followed by a procession of retainers that’s entitled “The Image of the King Yama Receiving the Prophecy.” On this plate, King Yama wears a flat hat with jade pieces suspended in front and in back of his hat. The top of the hat is decorated with the configuration of the Northern Dipper. King Yama is then followed by six Bodhisattvas.

Next in the procession is Daoming, who is typically portrayed as having a shaven monk head. Daoming is paired with the Poisonless Demon Dragon, who is a crown-bearing king. Daoming has his origins as a Tang monk who is said to have returned to life from the underworld. This tale includes the first major origin legend concerning the Ten Kings in the writing entitled “Record of a Returned Soul.” This legend, which was probably copied in the ninth century, is a legend about the monk’s journey through the chambers of hell by Daoming. Daoming is mistakenly taken to the underworld and released by King Yama to resume his original life on earth. On his way back to the world, Daoming encounters Jijang-bosal, who instructs him to study Jijang-bosal’s teachings and propagate his image when Daoming returns to Earth. Daoming also learns at this time that the lion is a manifestation of Munsu-bosal.

The Poisonless Demon King, on the other hand, originated in “The Scripture of the Original Vows of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva.” This writing is attributed to Siksananda (652-710 A.D.), and the writing mentions that the Poisonless Demon King presides over a hell of a boiling sea, and manifests as a Bodhisattva to respond to a Brahman woman’s concern for her deceased mother in the underworld. The woman was a manifestation of Jijang-bosal, whose filial devotion contributed to the mother’s release.

Although both Daoming and the Poisonless King originated in different sources, they appear as a standardized pair during the Goryeo Dynasty paintings of Jijang-bosal and the Ten Kings. And this continued during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). This pairing is unique to Korean paintings, and their pairing in these woodblocks are the earliest examples of this grouping.

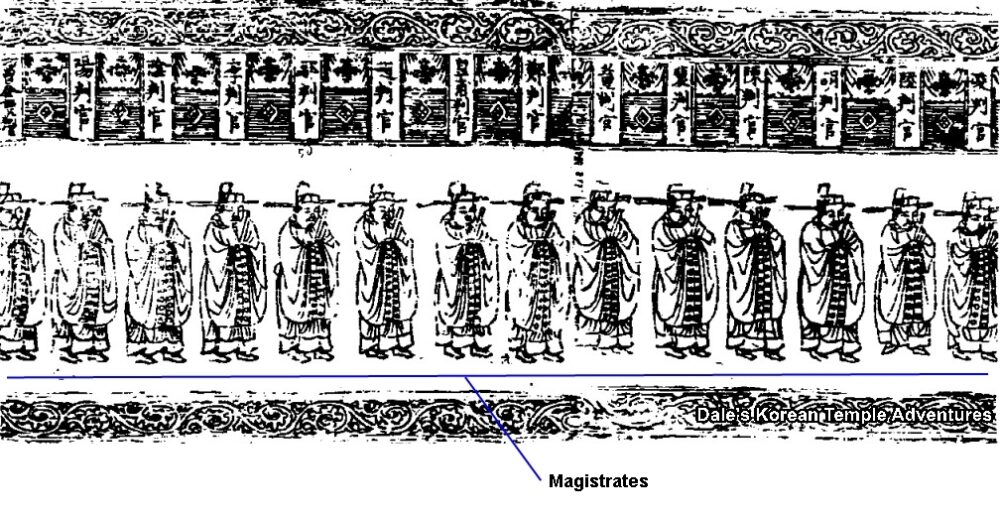

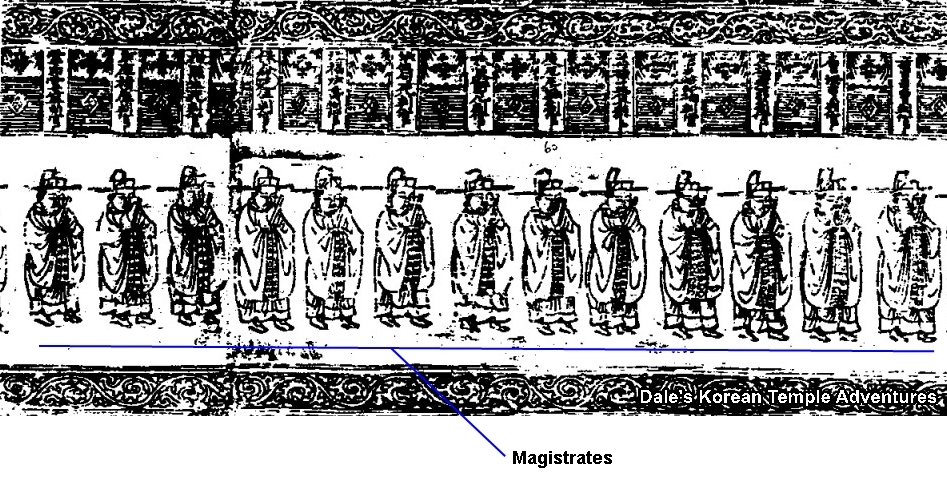

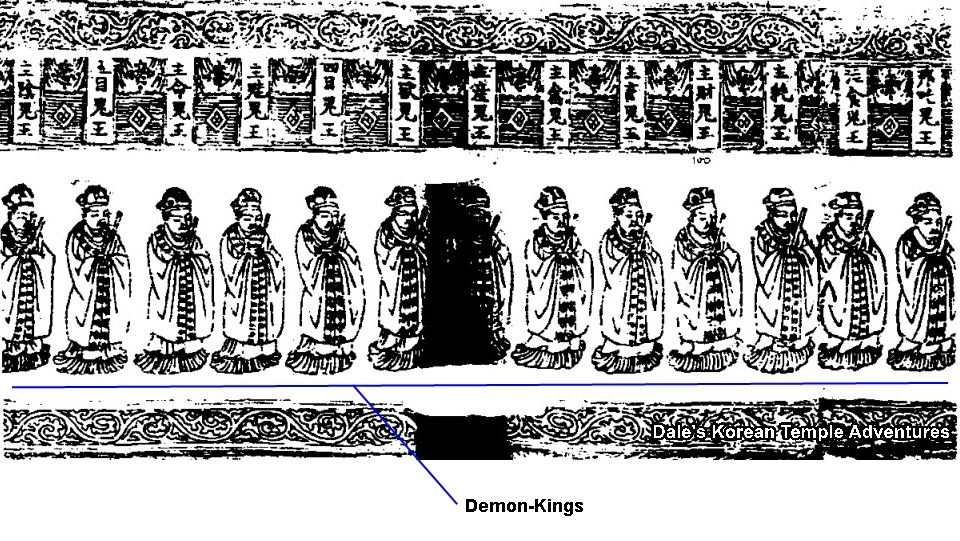

Next in line in the long procession are the Ten Kings with the tenth king being dressed in his traditional military uniform that indicates his authoritative position. After the traditional-looking Ten Kings comes an extensive list of magistrates which are 46 in total. They wear uniforms with squarish hats, a robe with wide sleeves, and they also hold scepters in their hands. They are a great example of the ultimate symbol of the bureaucracy found in the Buddhist underworld as imported from China. Some of these magistrates have Chinese places of ancient dynasties for names, while others have surnames found in both China and Korea. And yet a few more of these magistrates have names that are of transliterations of foreign names, while others have compound names describing their function.

What’s apparent is that during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) the underworld bureaucracy grew substantially. Led by the Ten Kings, the magistrates work for these judges to oversee and fulfill their underworld duties.

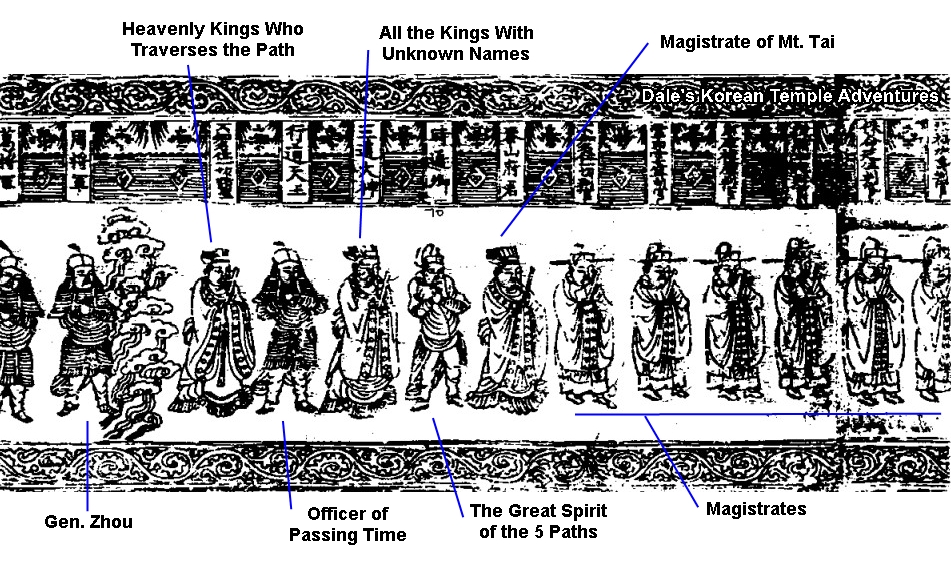

After these 46 magistrates follow five figures that appear in the middle of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings.” These five figures include the “Magistrate of Mt. Tai.” They administer to the underworld realm located beneath Mt. Tai. Also portrayed is the “Great Spirit of the Five Paths,” who is a deity mentioned in early biographies of the Buddha, Seokgamoni-bul. The Great Spirit oversees the five realms into which sentient beings can be reborn. These two figures are joined by “All the Kings with Unknown Names,” who are portrayed in kingly clothes, while the “Officer of Passing Time” appears in his shirt and pants. The final figure in this grouping of five is the “Heavenly King Who Traverses the Path,” and he wears military garb.

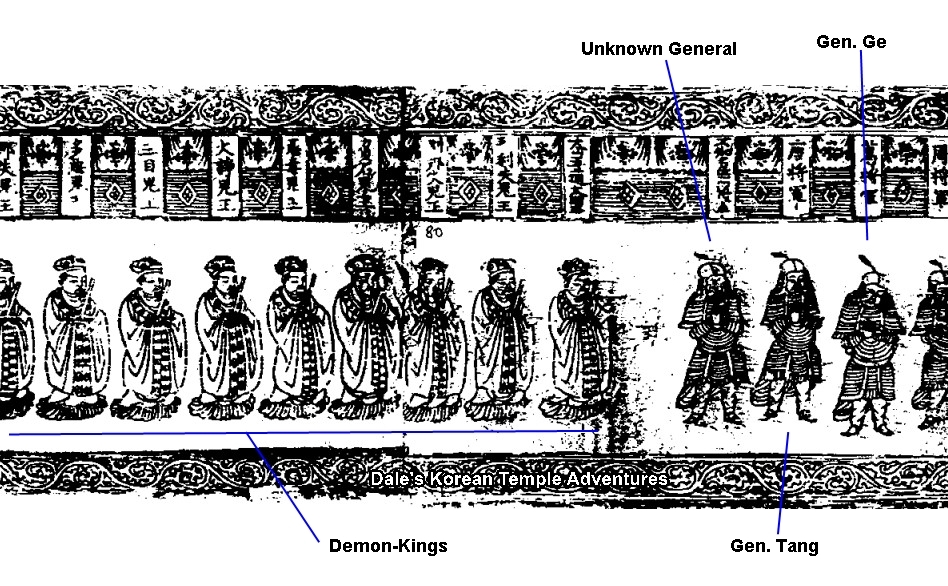

After these five figures, you’ll find four additional figures from the Haeinsa Temple edition of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings.” These four figures are of generals, who follow separated by a column of clouds. These four generals wear helmets with tassels and military clothing. What should be noted is that these generals are not specifically mentioned in the text; but since the tenth king, King Odojeonryun (오도전륜), is a general, their presence seems to have been multiplied. And these general’s names are probably a reference to the names of former Chinese Dynasties.

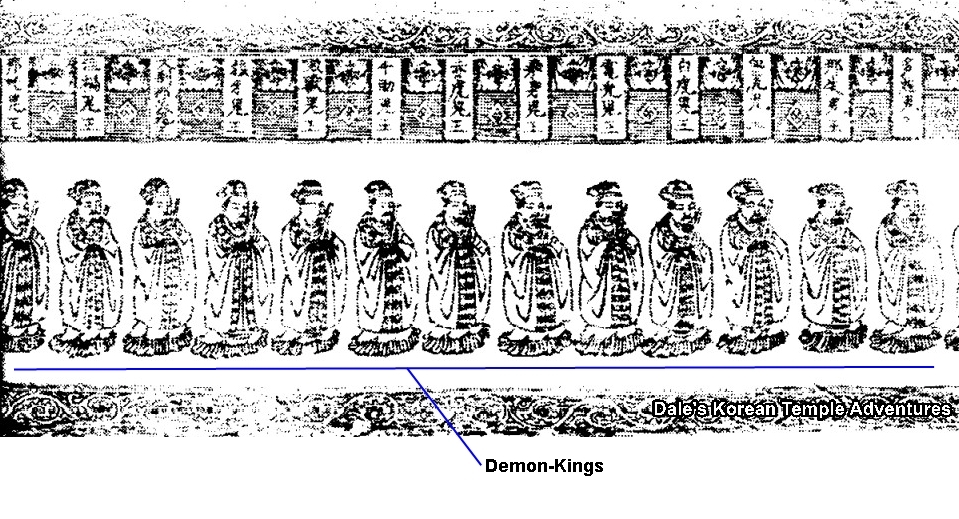

Next in the long artistic religious procession are 36 demon-kings. The number 36 is unprecedented in other artwork of the demon-kings related to the Ten Kings and their writing. The 36 appear wearing crowns and holding scepters in their joined hands. What’s interesting about these 36 demon-kings is that 26 are mentioned in the 7th century text “Scripture of Past Vows of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva,” in the chapter entitled “Commentaries of King Yama to the Sentient Beings.” And leading this list of 36 demon-kings is the “Great Bright King of the Great Mountain and Five Paths.” According to this writing, numerous demon-kings preside in a mountain named Cakravada (tieweishan) at Jambu-dvipa (yanfuti), which is found on the sea south of Mt. Sumeru. Their primary task concerns the protection of the virtuous from all types of calamities, and are protected in turn by Indra, Emperor of the Gods.

More specifically, in the Haeinsa Temple edition of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings,” it describes each of their tasks. And whether it’s discovering evil acts like the “Demon-King of Evil,” assessing battles like the “Demon-King of Great Battles,” or even governing a person’s lifespan like the “Demon-king Who Governs Lifespans,” they are all included in the list of 26 demon-kings. Other demon-kings included in this long bureaucratic procession are those named after animals like the “White Tiger” and the “Red Tiger.” As for their powers, some of the demon-kings can fly, others can travel as fast as lightening, while others have numerous eyes to see. However, while 26 of the 36 demon-kings are known scripturally, the remaining ten remain unknown in origin. With this in mind, the remaining ten could simply be inventions drawn from various Korean texts. And again, it should be noted that the large number of demon-kings presented in the Haeinsa Temple edition of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” are unique to this edition.

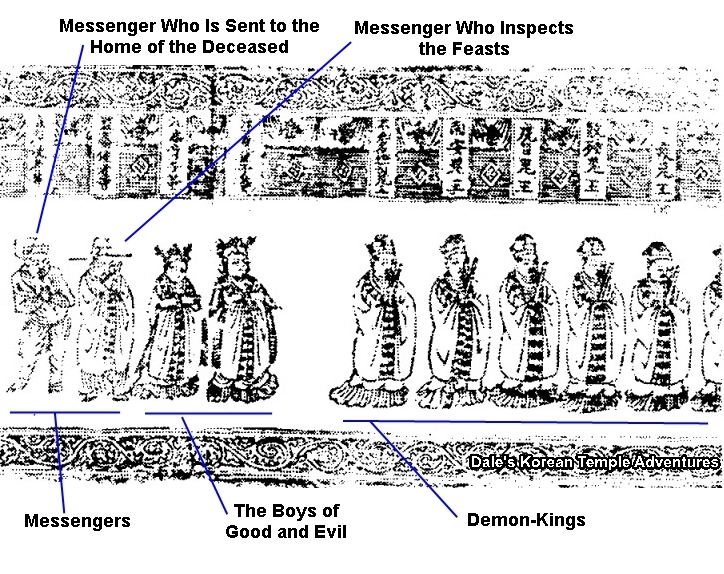

After the 36 demon-kings comes the “Boys of Good and Evil,” who record all the virtuous and evil deeds that one commits in their lifetime. This record is then presented to the Ten Kings upon one’s death. The origins of the “Boys of Good and Evil” are complex tracing back to indigenous Chinese sources on purgatory, as well as to Taoism. All of which was absorbed by Buddhist texts and transmitted to the Korean Peninsula.

What’s interesting about the appearance of these “Boys of Good and Evil” in the Haeinsa Temple edition is that they are depicted as female courtiers wearing small hair ornaments and carrying scrolls; while in Chinese sources like the Dunhuang illustrations from China, they appear as young boys with their hair rolled up into two buns and holding scrolls in their hands.

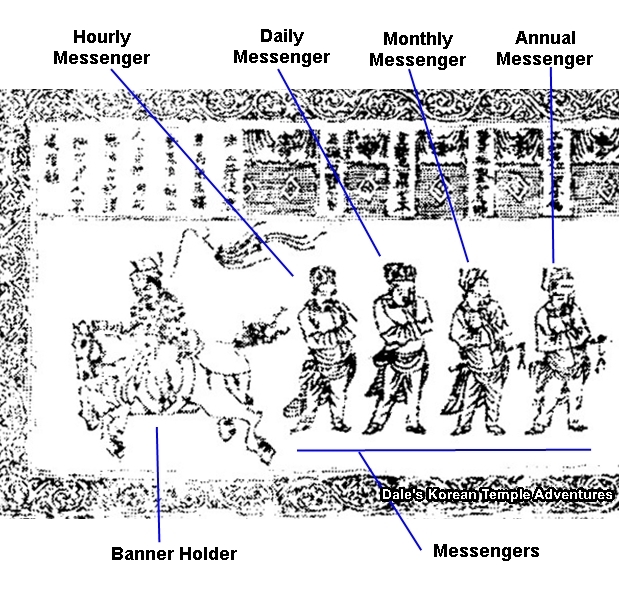

Following the two “Boys of Good and Evil” are six named messengers. In “The Scripture on the Ten Kings,” it’s mentioned that the Ten Kings will dispatch messengers riding black horses, holding black banners, and wearing black clothes to the homes of the dead to see what merit is being collected. The first of these messengers is the “Messenger Who Inspects the Feasts;” who, in turn, is followed by the “Messenger who Is Sent to the Home of the Deceased.” What should be noted about these two messengers is that they often appear alongside Jijang-bosal and the Ten Kings during the Goryeo Dynasty, which continues as individual paintings of the two messengers during the Joseon Dynasty.

These two messengers are then followed by different messengers which help denote times of the schedule. These messengers include the “Annual Messenger,” the “Monthly Messenger,” the “Daily Messenger,” and the “Hourly Messenger.” The task for these messengers is to inspect the homes of the dead during different times of the day and year. And their appearance in this expansive Haeinsa Temple edition only adds to the overwhelming bureaucracy that is the Korean Buddhist underworld during the Goryeo Dynasty.

And the very last figure in the very long procession is a mounted figure with a spotted shirt holding a banner. This figure gallops in the opposite direction and away from the long procession. This mounted figure is being dispatched to the home of the recently dead to inspect the offerings being made for the dead. And what’s interesting about this figure is that there is an inscription above this figure. It reads:

“The various kings will send out messengers riding black horses, holding black banners, and wearing black clothes. They will inspect the homes of deceased people to see what merit is being made. We will allow names to be entered, dispose of warrants, and pluck out sinners. May we not go against our vows.”

The Haeinsa Temple edition of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” is a wonderful example of the expanded depths and interpretative intentions that the Goryeo Dynasty took in both detailing the underworld, as well as the officials that ruled and administrated the underworld like the Ten Kings. Here are a few more examples of what separates the Haeinsa Temple edition from the early Dunhuang examples of “The Scripture on the Ten Kings.”

First, the Dunhuang examples that survive are mostly hand-copies executed with a brush, while the surviving early Korean examples like the Haeinsa Temple edition are heavily reliant on woodblock prints. The main reason for this difference is intentionality. The reason that “The Scripture on the Ten Kings” was commissioned was to accrue good karma for an easier afterlife. That’s why with the production of the woodblocks, it was easier to produce these texts and preserve them. It also helps explain why there was such a wide circulation of this text in Korean society, which largely originated from the Haeinsa Temple edition.

Another interesting difference found between the Haeinsa Temple edition and the early Dunhuang Chinese copies is who commissioned the texts. For the Dunhuang copies, they were commissioned by local scribes for both locals and local officials; while the Tripitaka Koreana (to which the Haeinsa Temple edition belongs), they were commissioned by powerful members of the Goryeo court.

And lastly, the Haeinsa Temple edition takes the Dunhuang copies and expands upon the bureaucratic officials to new numbers. The way this is done by the Korean edition is by extensively expanding the magistrates and the demon-kings in the text’s illustrations. In doing this, by expanding the number of figures in the Goryeo set, it helped to illustrate a far more complex and systematized underworld that now existed in 13th century Goryeo from 10th century China. It’s a change that China first initiated and would continue to evolve on the Korean Peninsula and beyond.

Conclusion on the Ten Kings of the Underworld

It’s truly remarkable the murky origins, the maturation, and evolution that the ideas and images of the Ten Kings took over centuries of time starting in China and further developing on the Korean Peninsula. The various texts and artwork are expressions of this change from humble beginnings to an expansive collection of officials and kings in the underworld. The evolution of the Ten Kings from China to Korea is an insight into the changes that took place and form over time in Buddhism. And this change, to this day, continues.

A Goryeo-era 13th century painting of two of the Ten Kings.