The Zenith – The Unified Silla Dynasty (668 – 935 A.D.)

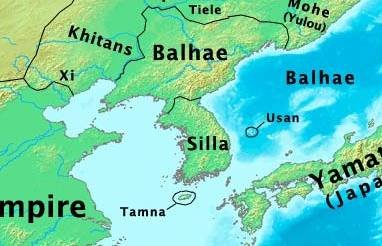

During the Unified Silla Dynasty (668 – 935 A.D.), Korean Buddhism would reach its zenith. A lot of the historic tangible cultural assets like National Treasures, Korean Treasures, and Historic Sites are datable to this time in Korean history. The Silla Kingdom, during the Three Kingdoms Period in Korean history, allied itself with Tang China in the mid-7th century. And in 660 A.D., in the sixth year of King Muyeol of Silla’s reign (r. 654-661 A.D.), the allied forces defeated the Baekje Kingdom (18 B.C. – 660 A.D.). Then, in 668 A.D., now under the new kingship of the famous King Munmu of Silla (r. 661-681 A.D.), as well as under the brilliant leadership of Kim Yusin (595 – 673 A.D.), they conquered the northern Goguryeo Kingdom (37 B.C. – 668 A.D.). Interestingly, the conquest of the Goguryeo Kingdom has a Buddhist aspect to it. During one of their largest battles with Goguryeo Kingdom forces, the devout Kim Yusin said, “When human strength has gone, depend on secret assistance.” After saying this, Kim Yusin went to a Buddhist temple where he intensely prayed. Only after saying his prayers did a large star fall from the sky onto the Goguryeo Kingdom camp. With this defeat, the reign of a Unified Silla was complete.

Buddhism was the dominant system of belief during the Unified Silla Dynasty. As a result, it played an integral role in both intellectual and cultural life. Numerous monks traveled to Tang Dynasty (618–690, 705–907 A.D.) in China to become better educated in Buddhism. And those that returned to the Korean peninsula brought back various Buddhist texts, relics, and sutras. This helped the peninsula develop both educationally and culturally. Buddhism continued to grow and flourish as it was viewed as protection against foreign invaders like the Chinese and Japanese. And to a small upstart nation like the Unified Silla Dynasty, the belief in protection was vital. And this protective belief was grounded in the nation’s belief in Buddhism.

The foundation to the vitality of the newly formed Unified Silla, other than Buddhism, were the Hwarang. The Hwarang, or Flower Youths, were trained in Buddhist teachings by Buddhist monks. The Hwarang were young warriors aged anywhere from between fourteen to eighteen years old. They were chosen from aristocratic families based on their looks and ability. Originally, the Hwarang were formed by King Jinheung of Silla (r. 540 – 576 A.D.), who was a devout Buddhist. Not only did this group allow the Silla Dynasty, during the Three Kingdoms Period, to thrive, but they also allowed it to outdistance any other kingdom on the Korean peninsula both politically and militaristically. Many famous kings and generals, like Kim Yusin, were ex-Hwarang. And their contribution to Silla society was immeasurable.

During this period in Korean Buddhist history, a primary shift was made from Gyo, or doctrinal learning, towards Seon, which was focused more on direct experience and meditation. Specifically, Seon doctrine taught that belief shouldn’t, and couldn’t, be grounded in writing alone. Instead, Seon believed that enlightenment could be attained through meditation and the mind. It’s believed that Seon Buddhism first entered Korea sometime during the 7th century during Queen Seondeok of Silla’s reign from 632 – 647 A.D. Unfortunately, it was only vaguely understood at this time. It wasn’t until the beginning of the 9th century, during Unified Silla, that it became more commonly practiced. As a result, this then led to the creation of the influential “Gusan Seonmun – 구산선문” during this time. Seon Buddhism’s great popularity stemmed from its wide acceptance in the countryside by its gentry. The reason for its acceptance was twofold. Obviously, it gave the people something to believe in; but it also provided a basis for countryside independence from the political power that was found in the capital of Gyeongju.

At this time, the Hwaeom sect of Buddhism was founded by Uisang-daesa (625 – 702 A.D.). It taught a doctrine of an all-encompassing harmony. This harmony focused on the belief that the one contains the whole, and that the whole contains the one. The purpose of this belief was to embrace all sentient beings, big or small, under a single Buddha mind. Another popular form of Buddhism at this time was Pure Land Buddhism. This form of Korean Buddhism focused on Amita-bul (The Buddha of the Western Paradise). It was especially popular among commoners. Pure Land Buddhism was popular among Koreans for two reason. The first is that it allowed people an escape from despair and gave them hope during a time in Korean history of danger and insecurity. The other reason it was so popular is that it was easy to practice. All it took for practitioners to show devotion was simply to chant, “Namu Amita-bul,” which roughly translates into English as, “I sincerely believe in Amita-bul.” In performing this chant, one could be reborn in the Western Paradise and escape this world’s pain and suffering.

There were a vast range of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that were highly popular during the Unified Silla Dynasty. At this time, Mireuk-bul (The Future Buddha) was highly popular. The reason that Mireuk-bul was so popular is that he was believed to have come to the Korean peninsula, in the form of Hwarang, to help Silla in becoming a Buddhist land. Another popular Buddha, as was already mentioned because of Pure Land Buddhism, was Amita-bul. Finally, and as a result of the Lotus Sutra, Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion) was highly popular, as well.

Much of Korea’s historic tangible past dates back to this period in Korean history in the form of temples, hermitages, statues, and pagodas. Such monks as Jajang-yulsa (590-658 A.D.) built Tongdosa Temple in 646 A.D. This made Tongdosa Temple the first Korean Buddhist temple to house the earthly remains of the Historical Buddha, Seokgamoni-bul. In addition to countless other monastic creations, the Silla nobility also helped in the spread of Buddhism’s popularity. These Buddhist buildings and structures were created by the nobility as a way of attracting good fortune during a time of frequent instability and insecurity. In addition to these structures, stupas (stone monuments that house the earthly remains of prominent monks) were increasing in number due to the increased popularity in Seon Buddhism and the idea of lineage. The oldest datable stupa was constructed during this period in 790 A.D.

The Unified Silla Dynasty was lucky early on to be ruled by notable kings like the first, King Munmu of Silla (r. 661 – 681). During his reign, he unified the peninsula and consolidated his rule that was centralized around a Buddhist belief system. However, as devout as King Munmu was, even he placed restrictions on Buddhism. In 665 A.D., during the fifth year of his reign, he ordered people not to donate land frivolously to Buddhist temples. He believed that temples had already become too prosperous for their own good. With all this being said, King Munmu still appointed monks as government officials. In 670 A.D., King Munmu appointed monk Sinhye as a government official, which highlights the influence Buddhism had not only on people, but also over government policy making. And in 671 A.D., the famous Buddhist monk, Uisang-daesa returned from China to warn Silla against a potential northern invasion. This was not the first time, nor would it be the last, that a Buddhist monk came to the aid of their nation.

Interestingly, it’s also at the height of Buddhism in Korea that its eventual ideological usurper, Confucianism, started to rival the more traditional system of thought in Korea. Confucianism gained traction among some Koreans because it stressed a set of moral standards for the world of human affairs. And as Confucians offered a beneficial system of moral and social values, Buddhism had a hard time competing with the hearts and minds of individuals in this sphere because Buddhism emphasized, and still emphasizes, personal salvation. While Confucianism had a long way to go to combat the dominant Buddhist belief system at this time, it eventually would in the centuries to come. But that change was still a few centuries off.

The peak of Korean Buddhism, both tangibly and culturally came in the mid to latter half of the 8th century. This was especially true during the reign of King Gyeongdeok of Silla (r. 742 – 765 A.D.). During the 13th year of his reign, the Hwangnyongsa Temple bell in Gyeongju was cast. And in 756 A.D., the Bunhwangsa Temple’s Yaksayeorae-bul (The Medicine Buddha) statue was made. And after his death, but under his initial guidance, the famous Bell of King Seongdeok was finally completed in 771 A.D. While Buddhism thrived under King Gyeongdeok of Silla’s reign, it would reach its heights during King Seondeok of Silla’s reign from 780 – 785 A.D. Both Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Hermitage were completed during his reign. They were constructed for then Prime Minister, Kim Daeseong’s past and present parents.

Unfortunately, the final century of Unified Silla Dynasty rule was one of constant civil war. And while Buddhism would remain the national religion under the succeeding rulers of the Korean peninsula, the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), Korean Buddhism would never achieve such splendid cultural heights as it did during the Unified Silla Dynasty.