Frogs and Toads – 개구리와 두꺼비

Introduction

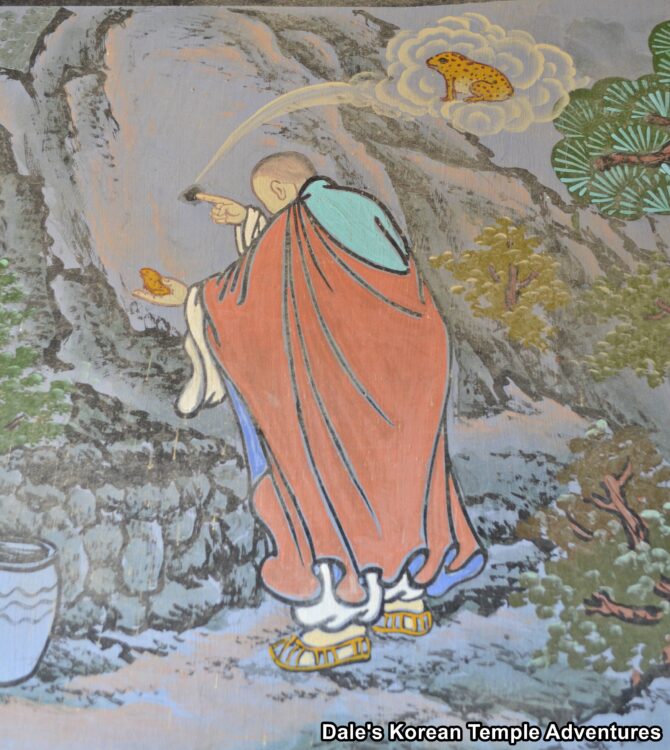

Rather interestingly, you’ll find several stories related to frogs, toads and Korean Buddhist temples. Some great examples of this can be found inside the Yeongsan-jeon Hall at Tongdosa Temple, which has a frog relief sitting in front of a lotus flower on the ceiling of this temple shrine hall. You can also find a similar image inside the Daeung-jeon Hall at Tongdosa Temple, as well. You can also find Nahan (The Historical Disciples of the Buddha) and dongja (attendants) holding a frog or toad, as well. They almost appear to be like a toy in their hands that they’re playing with. These frogs and toads can be found as paintings, statues, or in creation myths like at Jajangam Hermitage in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do on the Tongdosa Temple grounds. So why exactly are frogs and toads found so often in Korean Buddhism and its artwork?

The Huye and Hanga Myth

In Korea, kids believe that there is a rabbit on the moon pounding grain in a mortar. It’s also believed that there’s a toad living on the moon, as well. In ancient East Asian art, there are numerous descriptions about the features of the sky, the land, the sun, and the moon. So why exactly is there a toad living on the moon?

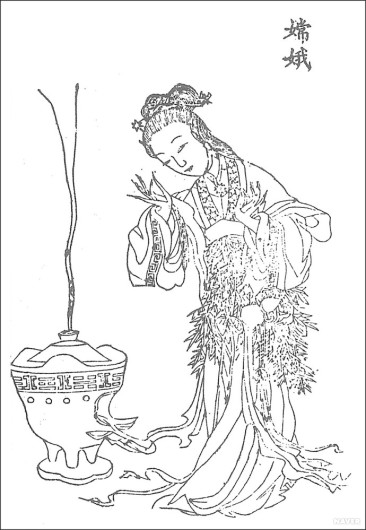

A long time ago, there was a man known as “Huye – 후예” who was a mythological archer. In Chinese, this archer is known as Hou Yi, and he’s referred to as Lord Archer, as well. Huye is often portrayed as a god of archery that descended from the heavens to aid humans. Huye saw that humans were suffering from having ten suns in the sky. Because of the ten suns, the ground was too dry and the mountains were on fire all the time, so Huye decided to shoot down nine of the suns with his arrows. Because he was so accurate, nine of the suns dropped from the sky. Since then, people could live in peace. As each of the suns fell, they became three-legged ravens. Because the tenth sun was so scared of being shot down, it hid, which plunged the earth into darkness. The Jade Emperor was angry at Huye, so he took away his position as a god and kicked him and his wife, Hanga – 항아 out of the heavens and into the human world.

Huye found living on earth to be difficult, but as long as he had his wife, Hanga, by his side, he wasn’t lonely. But even still, Huye longed to return to the heavens and be a god, once more. In fact, Huye tried so hard that he met the queen of the Taoist hermit Seowangmo – 서왕모. From Seowangmo, Huye received an elixir. The queen said to Huye, if both you and your wife, Hanga, take this, then you will live forever without disease. There are a few variations as to what happened next. One variation states that Hanga overheard that the elixir would grant immortality. So Hanga consumed the elixir while Huye was sleeping. Scared to be caught by her husband, Hanga ran away to the moon to escape her husband’s anger. In fact, Huye was so upset with his wife that he aimed one of his arrows at Hanga. However, he couldn’t bring himself to shoot an arrow at his wife and kill her. Over time, Huye’s anger dissipated. Eventually, Huye left Hanga’s favourite desserts and fruits outside each night to show that he had forgiven her.

Another variation describes how the Jade Emperor locked Hanga up in the moon. She cried so much from her guilt and loneliness. As a result, she turned into a toad. And the immortality elixir that she drank, that still remained in her throat, came out her mouth because of all the crying she was doing. This elixir then turned into a rabbit. It’s said that Hanga still lives on the moon and sings a song to her husband, Huye. This story is written in the Chinese encyclopedia known as the “Hoenamja – 회남자” in Korean. And in Eastern and Southeastern Asia, the Mid-Autumn Festival is celebrated to commemorate Hanga. This is a harvest festival, where it’s common to have fruits and sweets placed on an open outdoor altar for Hanga, so that they can be blessed.

The Frog and the Toad: A Korean Symbol for Foresight, Fecundity, and Abundance

In Korea, the frog is a symbol for foresight, fecundity, and abundance. Historically, Koreans believed that frogs had foresight because frogs can sense the fall of rain before it happens. An example of this can be found during the Silla Dynasty (57 B.C. – 935 A.D.). During this time, Queen Seondeok of Silla (r. 632 – 647) predicted three things. In one of these three predictions, and on a cold day, frogs cried out for four days and nights at Okmunji Pond at Yeongmyosa Temple. This happened despite the fact that it was winter. So Queen Seondeok thought that something was off. So Queen Seondeok decided to send two thousand soldiers to be close to the neighbouring valley. When the soldiers arrived just outside the valley, they found some five hundred Baekje soldiers hiding in the valley. The two sides fought, and the Silla soldiers won. In fact, a portion of these soldiers were able to protect the palace where the queen resided. Of course, this happened because of Queen Seondeok’s foresight as a leader, but people also believed that because of the frogs’ foresight, it helped save the Silla Kingdom.

Inside the Samguk Sagi, or “History of the Three Kingdoms” in English, specifically in the “Kings’ History of Goguryeo,” you’ll find another story about a frog’s foresight. In this story, when people saw frogs fighting, they expected the decline of north Buyeo. And whenever the country was thrown into turmoil and chaos, people would witness frogs crying; either that, or a group of frogs would be found dead. As a result, people of Goguryeo believed that frogs were a symbol of foresight.

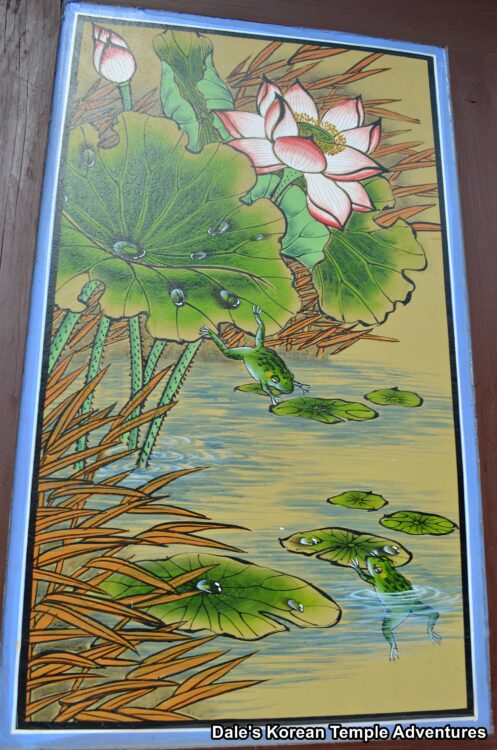

And yet another story about frogs relates to them as a symbol of fecundity and abundance. As is commonly known, frogs lay a lot of eggs. In fact, some three thousand can be laid at one time. So traditionally, in Korea, honeymooners would have folding screens and hanging scrolls with frogs painted on them near the bedside in hopes of having numerous children. Additionally, fecundity means abundance; and in Korea, abundance was a sign of good luck. So there is a lot of artwork in and around temples with frogs or toads because they are believed to be a sign of good luck. An example of this is a Nahan holding a frog. More specifically, you can find a Yeongsanhoesang-do – 영산회상도 at the Tongdosa Temple museum originally from the neighbouring Munsusa Temple in Ulsan. There are two unique features to Nahan in this painting. First, you can find a frog being held in the hand of the Nahan. The Nahan is smiling, while the other Nahan are surprised. The reason for this surprise is that frogs are considered to be hard to find; and as a result, a symbol of good luck. This temple artwork is humourous example of late Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) Buddhist expression and artistry.

The Frog and the Buddha

One day, a frog wanted to listen to the Buddha’s teachings, so it came out of a pond to listen. Heading towards the Buddha, the frog was accidentally killed by one of the listener’s canes, so the spirit of the frog was separated from its body. When the frog awoke, the frog realized that it had been reborn on top of the Buddha’s land. The frog couldn’t believe it. The frog thought, “I was an animal in my former life. Then how could I be reborn in this heavenly palace?” With this, the frog realized that it had sacrificed itself to listen to the Buddha’s teachings. So the frog finally made its way towards the Buddha. There, it prayed appreciatively. Seeing this, the Buddha made the frog a saint. This story is written in the Gyeongryul-isang. Usually frogs are discussed passingly in other Buddhist texts; however, in this Buddhist text, the frog is elevated above its lowly station in life. More specifically, that even a lowly creature can become something more with an earnest heart and the teachings of the Buddha.

Example of Frogs and Toads

Frogs and toads are commonly found throughout Korean Buddhist temples and hermitage like the aforementioned ceiling of the Yeongsan-jeon Hall at Tongdosa Temple. It can also be found at Hyuhyuam Hermitage in Yangyang, Gangwon-do and around the main hall at Jajangam Hermitage in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do. Another place that you can commonly see frogs is on the art adorning a Jangeom Sumidan (altar). It’s common to find a frog relief sitting atop a lotus flower in this style of Buddhist artwork.

Citation

I would like to thank the Wolgan Tongdo – 월간 통도 for a large portion of this insightful information.

I would also like to thank Irene Ye for this wonderful translation of the original article. If you would like to get in contact with Irene Ye for her to do some translation work for you, please let me know, and I will get in contact with her.

One Comment

Pingback: