Colonial Korea – Muwisa Temple

Temple History

Muwisa Temple is located in the southern portion of the picturesque Wolchulsan National Park in Gangjin, Jeollanam-do. According to both the Cultural Hermitage Administration website and the Muwisa Sajeok, or “The History of Muwisa Temple” in English, the temple was first built in 617 A.D. by the famed monk Wonhyo-daesa (617-686 A.D.). It was named Gwaneumsa Temple (The Bodhisattva of Compassion Temple). But this is hard to believe for a couple of reasons. First, Wonhyo-daesa would have been just a one year old when he first built Muwisa Temple. Additionally, Wonhyo-daesa was a Silla monk. The Silla Kingdom (57 B.C. – 935 A.D.) was in open conflict, and eventual war, with the Baekje Kingdom (18 B.C. – 660 A.D.), which is where Muwisa Temple was located.

What is perhaps more plausible, but still questioned by some, is that Muwisa Temple was first established by Doseon-guksa (826-898 A.D.) in 875 A.D. At this time, the temple was called Galoksa Temple. Whatever the case may be, Muwisa Temple was definitely established by the early 10th century by Seongak-daesa (864-917). Muwisa Temple grew into a major Seon Buddhist temple in the early part of the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392).

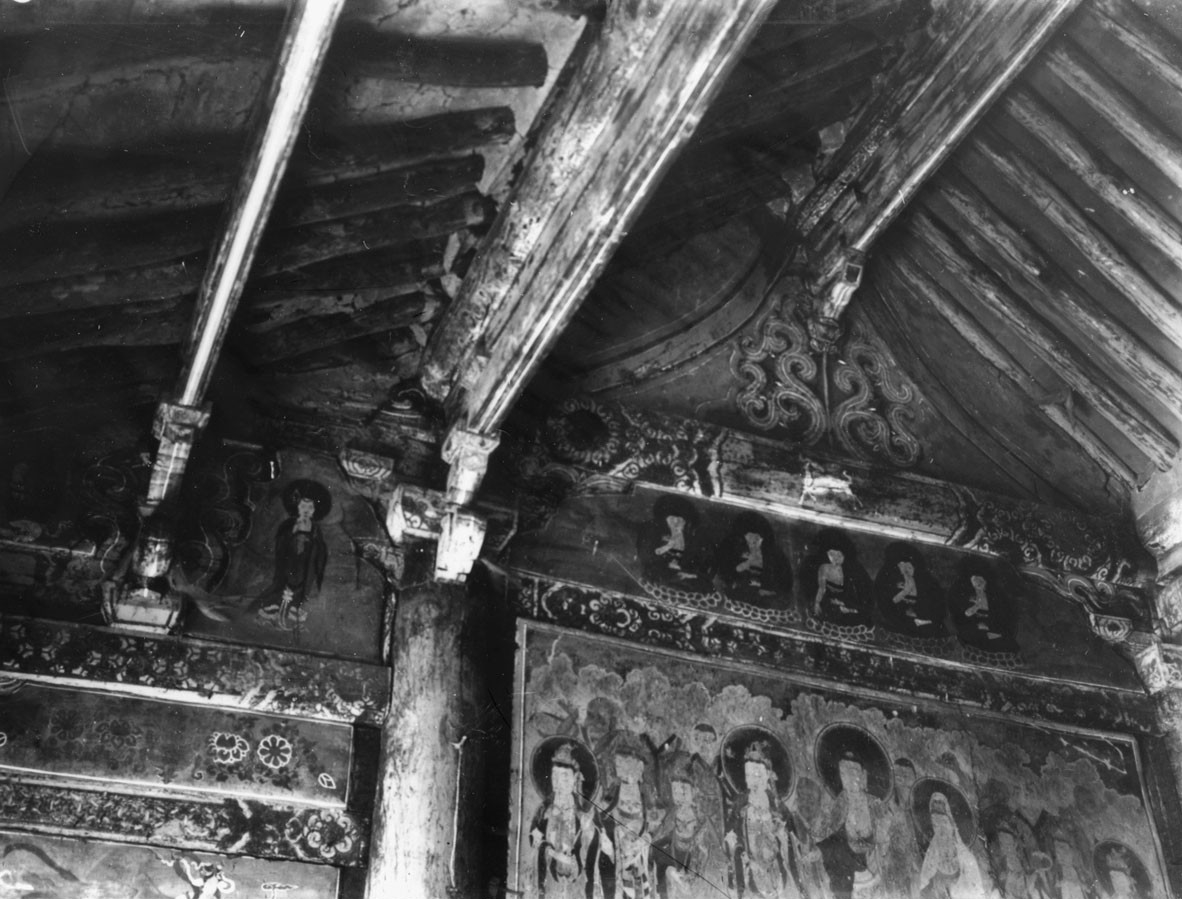

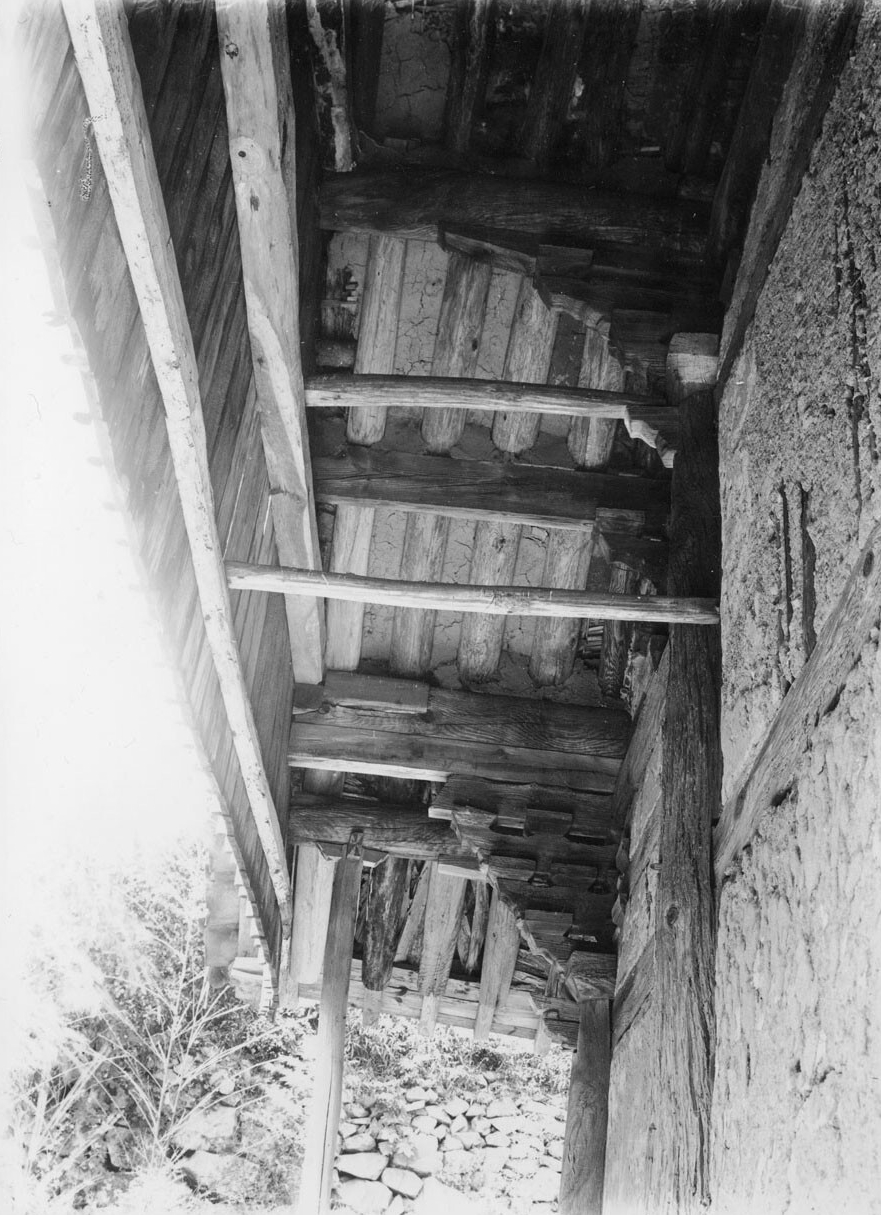

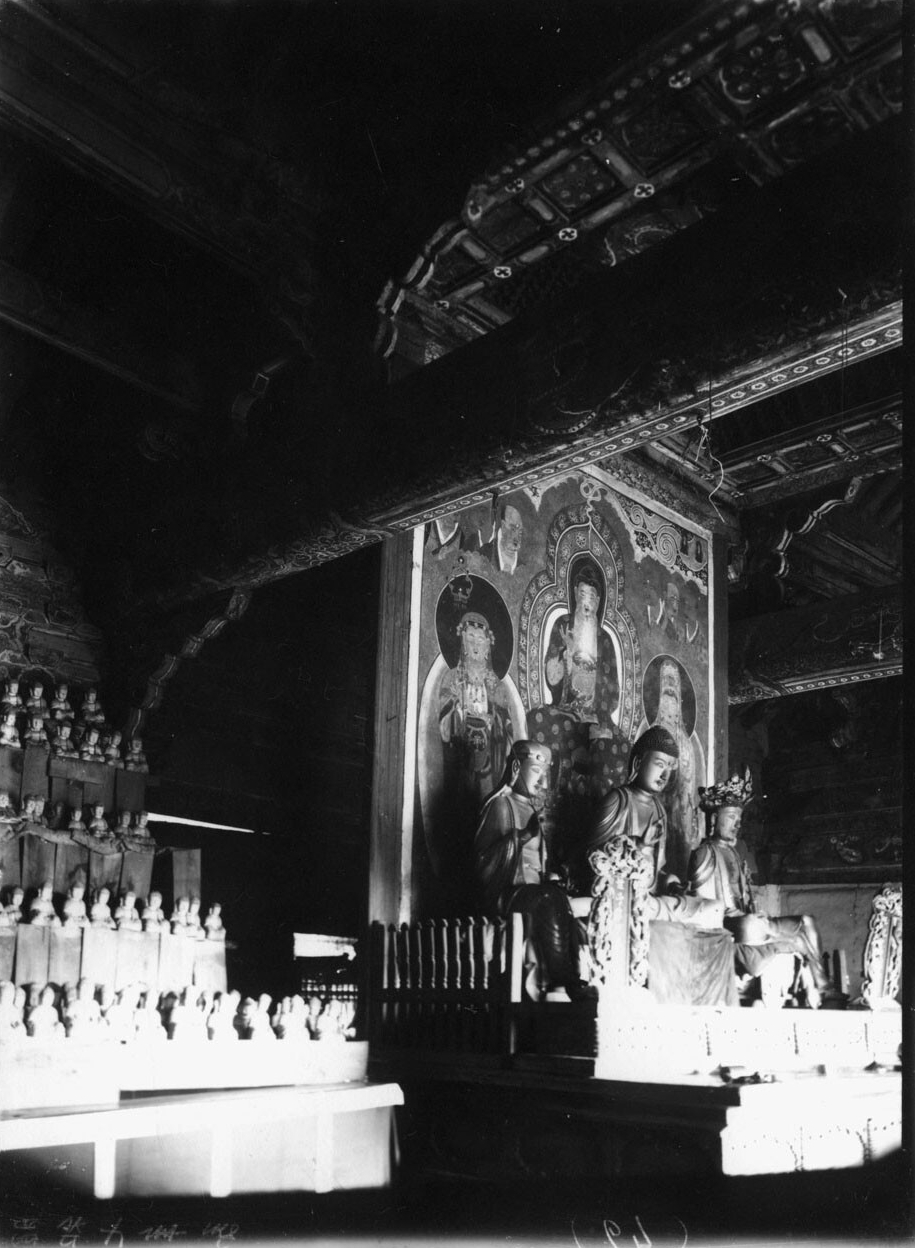

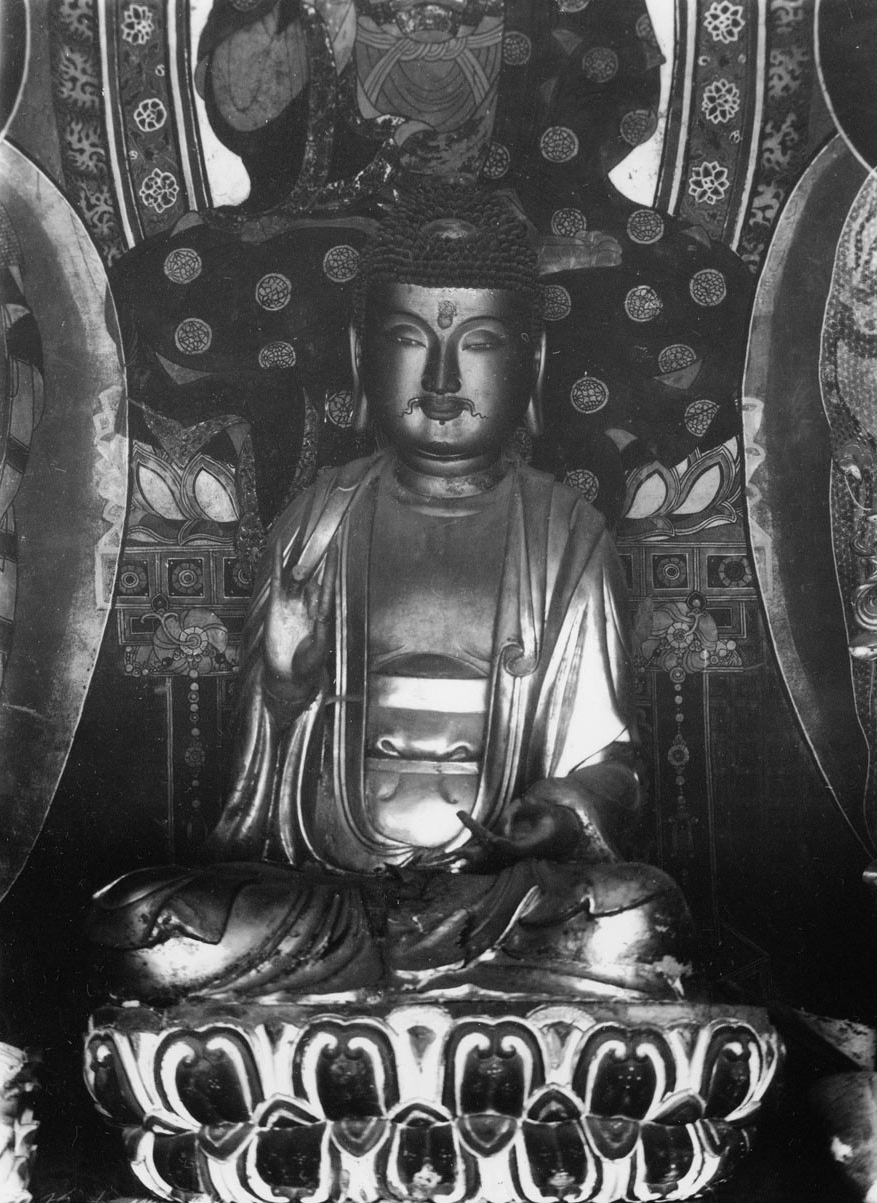

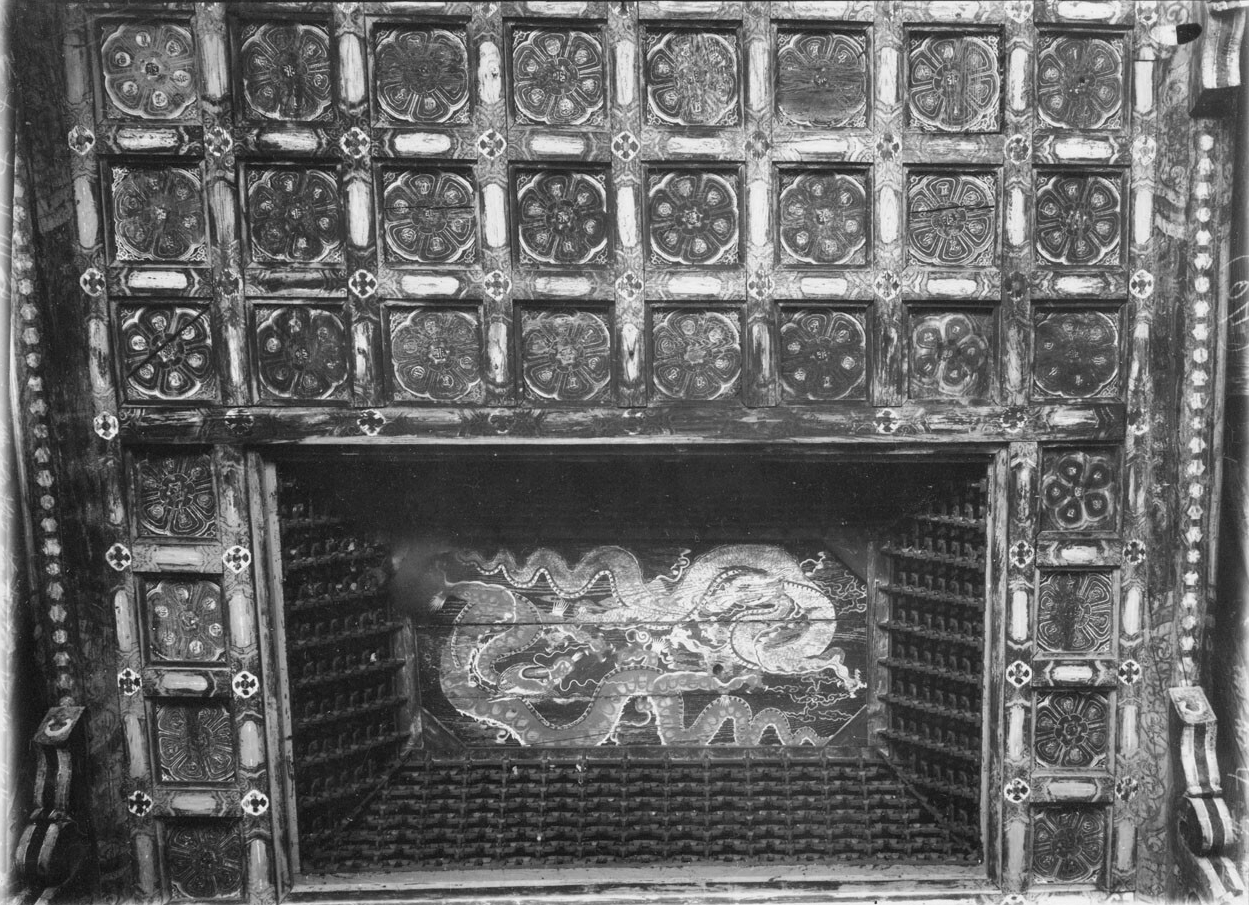

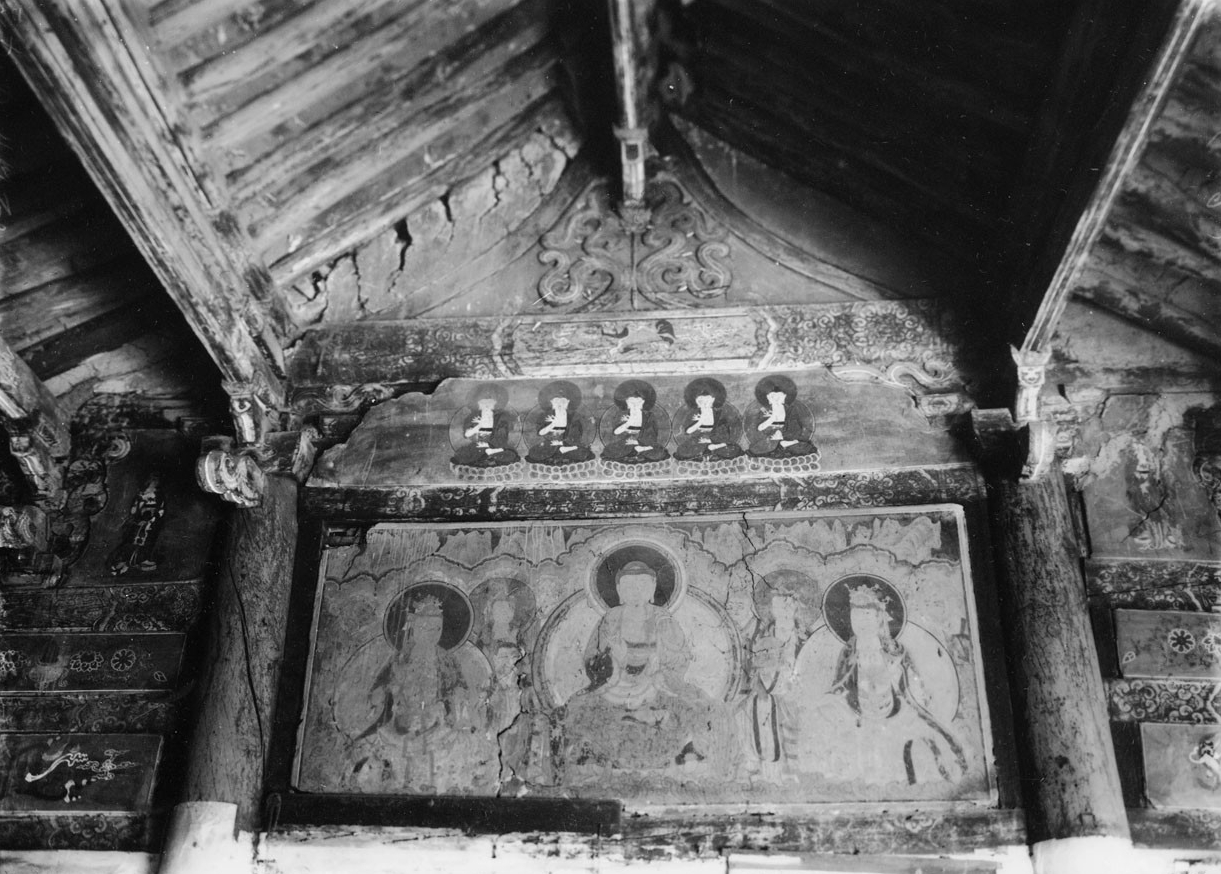

Before the 10th century, the name of the temple changed once more, this time, to Muwigapsa Temple, and it became a Seon temple. Later on, the temple would become a Cheontae temple with the growing popularity of the Cheontae teachings in the 11th century. According to the Muwisa Sajeok, or “The History of Muwisa Temple” in English, Muwisa Temple fell into disrepair and was rebuilt and renamed Suryuksa Temple, which literally means “Water Land Temple” in English. The reason for this change of name is that historians believe that the temple became a site for the ceremony for the rites of the dead known as the “Suryuk-je – 수륙재” in Korean. This is a Buddhist ritual to help console the spirits of the dead. Specifically, it was a ritual for the war dead, both friendly and foe, that couldn’t reincarnate. This helps to explain why the main hall, the Geukrakbo-jeon Hall, at Muwisa Temple is dedicated to Amita-bul (The Buddha of the Western Paradise). The present Geukrakbo-jeon Hall was built in 1430 A.D.

In 1550, during the mid-Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), the temple was rebuilt and renamed Muwisa Temple by the monk Taegam. Tragically, Muwisa Temple was destroyed, in part, by fire during the Imjin War (1592-1598). Fortunately, the Geukrakbo-jeon Hall was spared.

In 1934, the Geukrakbo-jeon Hall became National Treasure #13 during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945). And in 1974, after years of only having a handful of temple buildings, new construction took place at Muwisa Temple. In total, Muwisa Temple is home to two National Treasures and an additional four Korean Treasures.

Colonial Era Photography

It should be noted that one of the reasons that the Japanese took so many pictures of Korean Buddhist temples during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945) was to provide images for tourist photos and illustrations in guidebooks, postcards, and photo albums for Japanese consumption. They would then juxtapose these images of “old Korea” with “now” images of Korea. The former category identified the old Korea with old customs and traditions through grainy black-and-white photos.

These “old Korea” images were then contrasted with “new” Korea images featuring recently constructed modern colonial structures built by the Japanese. This was especially true for archaeological or temple work that contrasted the dilapidated former structures with the recently renovated or rebuilt Japanese efforts on the old Korean structures contrasting Japan’s efforts with the way that Korea had long neglected their most treasured of structures and/or sites.

This visual methodology was a tried and true method of contrasting the old (bad) with the new (good). All of this was done to show the success of Japan’s “civilizing mission” on the rest of the world and especially on the Korean Peninsula. Furthering this visual propaganda was supplemental material that explained the inseparable nature found between Koreans and the Japanese from the beginning of time.

To further reinforce this point, the archaeological “rediscovery” of Japan’s antiquity in the form of excavated sites of beautifully restored Silla temples and tombs found in Japanese photography was the most tangible evidence for the supposed common ancestry both racially and culturally. As such, the colonial travel industry played a large part in promoting this “nostalgic” image of Korea as a lost and poor country, whose shared cultural and ethnic past was being restored to prominence once more through the superior Japanese and their “enlightened” government. And Muwisa Temple played a part in the propagation of this propaganda, especially since it played such a prominent role in Korean Buddhist history and culture. Here are a collection of Colonial era pictures of Muwisa Temple through the years.

Pictures of Colonial Era Muwisa Temple

1932

Pictures of Colonial Era Muwisa Temple

1934

Pictures of Colonial Era Muwisa Temple

Specific Dates Unknown (1909-1945)