Colonial Korea – Tourism in Korea

Introduction

During the Japanese Colonial Rule in Korea (1910-1945), tourism in Korea was an expanding and expansive trade. In fact, in 1936 alone, the number of Japanese inbound tourists to Korea numbered 42,586 individuals. In total, these people spent a total of 107,688,000 yen (per person, this equals 2,529 yen). And even though it only represented a small fraction, just 4 percent, of Japan’s overall trade (including imports and exports), it was a welcomed influx of capital. And the reason that Korea became such a popular destination for the Japanese was that it helped to justify the annexation of Korea. It did this through a number of ways including through tourist slogans and propaganda that helped promote the notion of a “return” and reunion of the Japanese and Korean people.

Furthermore, the Japanese Imperial government increased investments in Korea, whether it be through infrastructure or transportation, by convincing rich Japanese businessmen that the Korean Peninsula was ripe with endless investment opportunities including tourism. As such, the Japanese government through the JTB (The Japanese Tourism Bureau) and the CGK (Colonial Government-General of Korea) promoted Korea to the Japanese population as the most picturesque and historically “authentic” location in the Japanese empire that was filled with decaying ruins, old customs, beautiful women, and luxury accommodations (that could and would be built by the Japanese). In doing this, and through the guise of both business opportunities and tourism, the Japanese government created an image of imperialism, while also promoting a sense of nostalgia. In the end, Japan was able to curate an effective business plan that modernized Korean infrastructure like rail and roads, while also earning additional money through spending and taxation through tourism on the Korean Peninsula during Japanese Colonial Rule to help support their aggressive expansionist military campaigns.

Reasons for Japan’s Growth as an East Asian Empire (1894-1912)

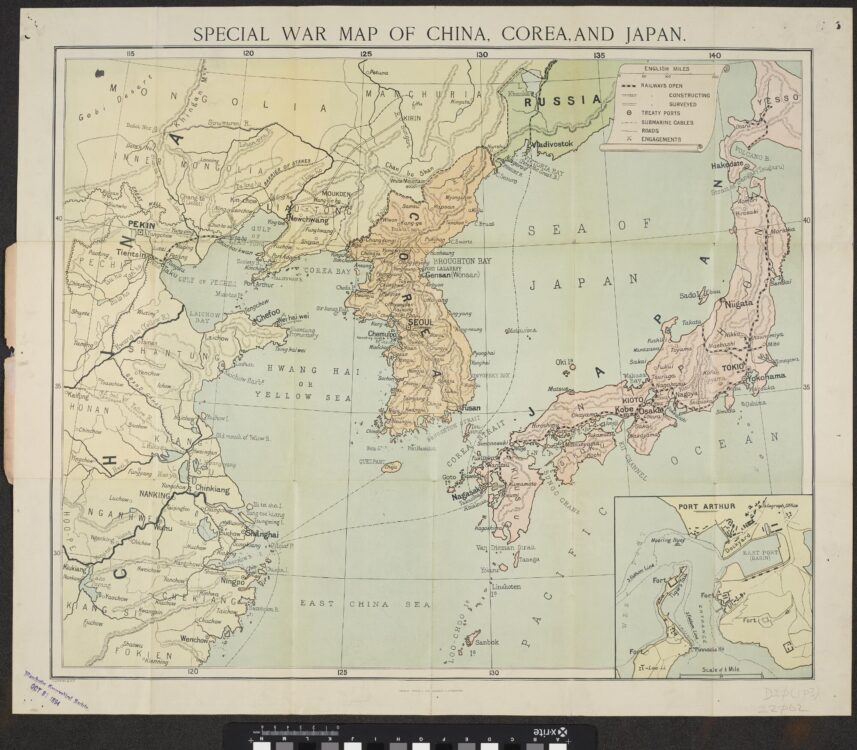

As a nation, Japan started to appear as an imperial power following two military campaigns. The first of these victories took place during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). With these two key victories, Japan emerged as a nation ready to enter the world stage as a dominant force. As such, Japan took their first steps to become a regional colonial power. Soon Japan attempted to find opportunities for eager businesses in new colonies through Japanese goods. With this in mind, colonial administrators spearheaded opportunities through industrial development and tourism by searching for new resources and customers. Japan would go on to develop colonial opportunities in Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, as well as territories in Siberia and the South Pacific. But of all these colonies and territories, it was the opportunities found in Korea that excited the imagination of Japan’s citizens and governmental officials the most. There were several reasons for this.

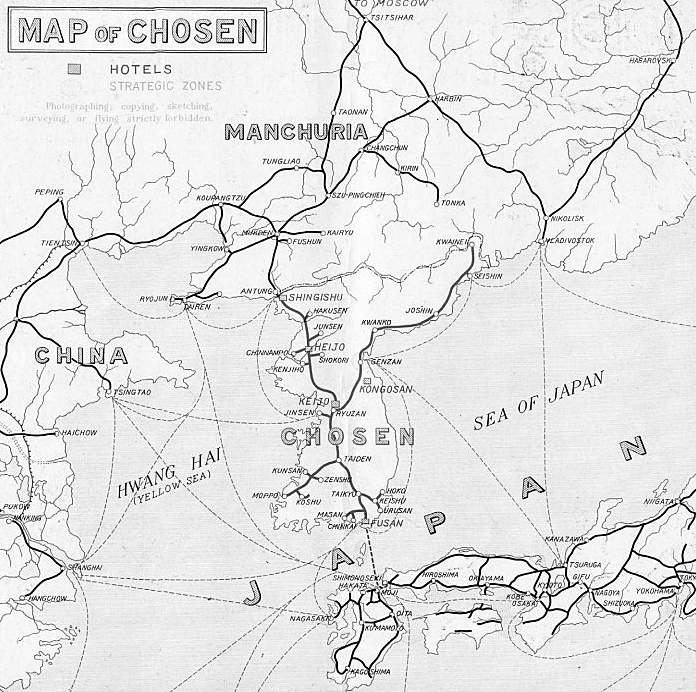

The first of these reasons was the close geographically proximity found between the two nations. Also, and because of its location between Japan and China, the Korean Peninsula acted as a key strategic location, as well. For this reason, Korea was a prime target for intensive and extensive infrastructure and industrial investment by the Japanese. It was in their best interest. In fact, and as early as the 1890s, colonial administrators, companies, and the military were all involved in developing extensive transportation systems, as well as producing communication links and military facilities. This was done by building harbors, bridges, railways, road, and urban tram systems. Furthermore, major banks and companies like the Bank of Chosen, Mitsui Heavy Industries, Ogura Mining Company, the Japan Mail Steamship Company (Nippon Yusen Kaisha, or NYK for short), and the Japan Mail Steamship Company (or SMR for short), to name but a few, meticulously calculated import versus export costs and the profit margin found in this enterprise. Such things as the import and export of agricultural products (rice and cotton), the import of military supplies and weapons, and the mobilization of troops to help reinforce the Manchurian front were all key factors.

One example of this meticulous calculation can be found with the signing of the Portsmouth Treaty in 1905, which saw the Korean branch of the Japanese Imperial Railways, and which was also known as the Colonial Government Railways Company (or CGR for short), had opened-up the main north-south railway lines, the Keifu (Gyeongbu-seon) railway and the Jinsen (Incheon) line. These major railway arteries connected the major cities of the Korean Peninsula directly to the ports of Fusan (Busan), Keijo (Seoul), and Incheon. Not only did this railway system help connect and transfer daily freight and mail from the port of Shimonoseki in Japan to the ports of Korea, but it also helped transport hundreds of thousands of Japanese settlers to various destinations throughout the Korean Peninsula and beyond.

In fact, and according to statistics published by the CGK, the number of passengers increased on the state railways tenfold from 2,024,000 to 20,058,000 individuals in a span of sixteen years from 1911 to 1927. Additionally, freight increased in the same time period from 888,000 tons to 5,570,000 tons. It should come as no surprise then that the Japanese extended the mileage of tracks from 1084.7 km (674 miles) to 2341.6 km (1455 miles). All of this resulted in the growth of revenue nine-fold from 4,095,000 yen to 36,364,000 yen in 1929 according to the CGK.

The second reason that the Japanese government was excited about potential opportunities in Korea is Korea’s strategic location in connection to transportation and as a potential commercial hub for the expansion of the Japanese Empire. More specifically, major corporations and ambitious politicians invested heavily in developing tourism and cultural destinations in Korea like historical parks, museums, zoos, botanical gardens, hot springs, hotels, and mountain resorts. Tourism was a gateway for many Japanese entrepreneurs to help profit off the newly acquired colony.

And the third reason for such interest in Korea by the Japanese was that the Korean Peninsula was the only colony where the Colonial Government-General of Korea (1910-1945) sponsored more than four decades of continuous archaeological and historical surveys in order to help maximize the collection of documents, register artifacts, and excavate buried objects; which, in turn, would act as a major historical destination for Japanese tourists. This was particularly the case with Korean Buddhist temples and temple sites. Because of the two nation’s shared religious ancestry, Japanese tourists flocked to historic cities like Gyeongju to immerse themselves in Korea’s religious past. It’s also another reason why the Colonial Government-General of Korea invested so heavily in repairing and maintaining Korea’s Buddhist temples. As a result, the Imperial University in Japan had archaeologists that were willing and eager to conduct surveys and research in Korea, especially since they were prevented from doing so in Japan according to the Imperial Household Agency.

State Sponsored Tourism (1912-1945)

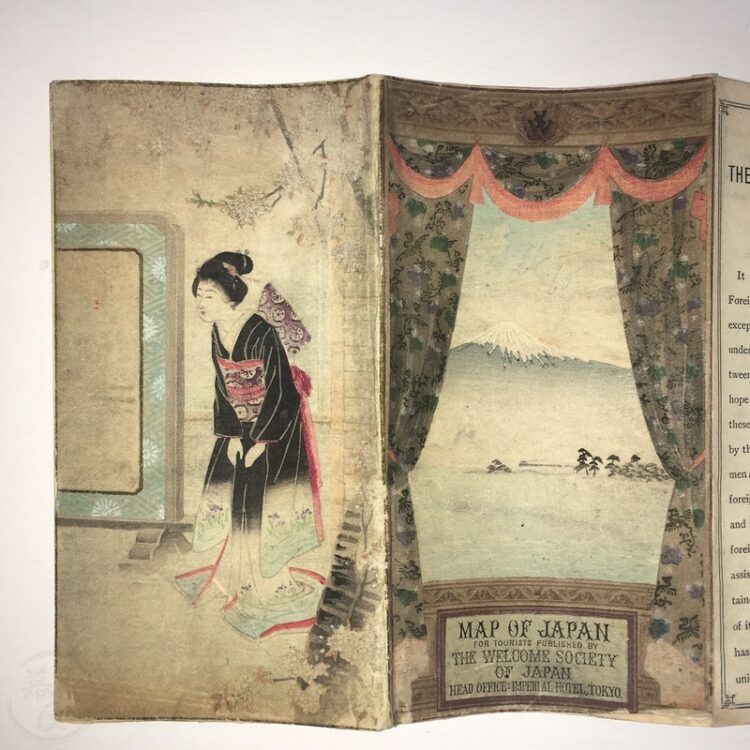

From the beginning of the Japanese Colonization of Korea, and even before, Japan’s tourism policy was directed at promoting international trade and commerce. The “Welcome Society of Japan,” or the “Kihinkai” (Society of VIPs) in Japanese, was Japan’s very first tourist board. It was founded in 1893. The board was sanctioned by the Imperial Household, and its board members included such individuals as high-ranking foreign ambassadors, dignitaries, aristocrats, and leading entrepreneurs who operated the society from the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce. The aims of the society, according to the preface to their 1908 edition of the “Guidebook for Tourists” was “bringing within reach of tourists the means of accurately observing the features of the country, and the characteristics of the people; aiding them to visit places of scenic beauty; enabling them to view objects of art and enter into social or commercial relations with the people; in short, according them all facilities and conveniences toward the accomplishment of their several aims, their indirectly promoting, in however small a degree, the cause of international intercourse and trade.”

Also around this time was the development of the much larger corporate entity, the “Japan Tourist Bureau,” or JTB for short, which was established in 1912 at the Japan Imperial Railways Corporate Headquarters (or JIR for short). Through their connections, JTB was able to convince shipping magnates, department stores, and the Tokyo Imperial Hotel management, to name but a few, who were asked to join in the venture that aimed at transforming and transporting Japan.

And the immediate financial goal of the JTB, which focused on various tourist projects, was to help secure new foreign revenue to help alleviate Japan’s severe economic crunch that was happening because of the drain caused by expensive military equipment and expansionist campaigns. And the other goal of JTB, which seemed a bit more diplomatic, was to find a way to help promote a more modern and civilized image of Japan to the world. The reason for this is that Japan’s reputation had taken a beating, especially after the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905).

In total, JTB opened colonial outposts in Taiwan, Manchuria, and Korea in 1912. This was the very same year that the organization was founded in Tokyo. The goals of the JTB Chosen Branches in Korea, and the Colonial Government Railways Company, was the same as their parent company. As such, their goal was to attract as many passengers as possible to Colonial Korea, so that the Japanese government and their leading companies could recoup some of their enormous financial investments made while building infrastructure on the Korean Peninsula which had and would continue to help facilitate Japanese efforts in East Asia through transportation and communications.

By 1914, various colonial branches of the JTB were distributing some 3,000 maps printed in English. Not only were they covering Japan, but they also included Seoul (Keijo), Dairen (Dalian, China), and Taipei (Taihoku). At the end of World War I, and with Europe ravaged by economic inflation and crisis, the JTB found it difficult to attract foreign travelers to East Asia. Europeans simply weren’t buying travel coupons; so instead, the JTB created an alternate business plan in 1918. This new business plan saw JTB starting to sell packaged tours to the colonies for domestic Japanese consumption. As a result, JTB started to provide Japanese language advertising that involved printing and distributing travel brochures, maps, and postcards of seasonal attractions. Also produced were various travel magazines.

With the rise of domestic ticket sales in Japan, the JTB persuaded major department stores to sell these tourist packages. And the peak of outbound tourism from Japan peaked from 1925-1935 in the pre-war years. These tourists included a wide range of classes and occupations. Some tourists were teachers, while others were students, soldiers, and businessmen. These tourists were typically of the educated class that were hungry for history and Japan’s old and new place in it. Tourism, in time, would become Japan’s fourth most important source of foreign revenue behind only cotton, raw silk, and silk products.

Because of the purposeful destruction of documentation, it’s hard to get a complete and accurate accounting of just how many tourists not only traveled to Korea but to other Japanese colonies, as well. The nearest we can get is from the JTB in Manchuria in 1940. In total, the JTB conducted a total of 9,108 guided tours to both Manchuria and Korea. Of these tours, which comprised of some 398,299 tour group members, they included Manchurians, Japanese, and foreigners participants. These figures are but a glimpse into the vibrant tourism industry conducted by the Japanese state in the late 1930s and early 1940s before its complete collapse in 1943.

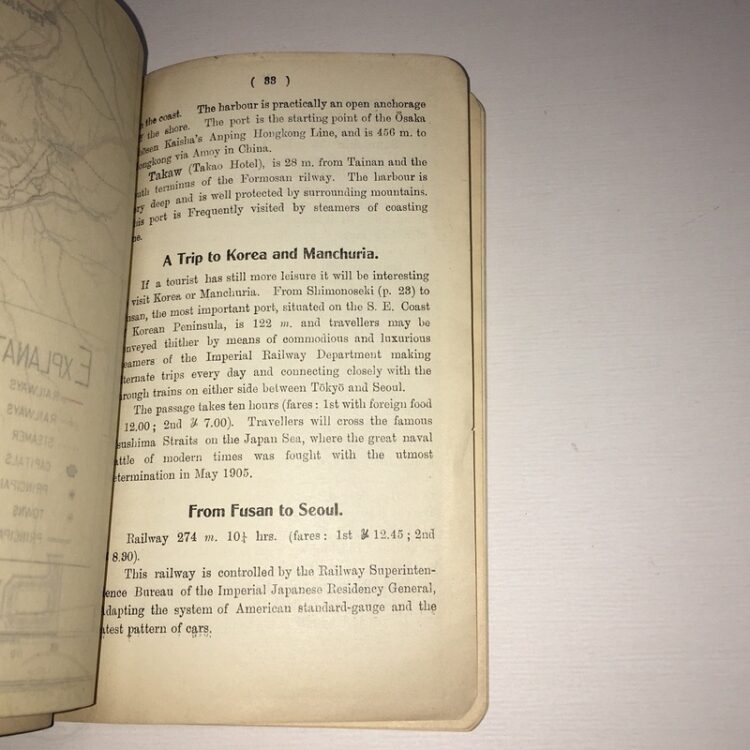

The Organization of Tourism Information through Guidebooks

The very first documented tour group of private citizens to visit Korea and Manchuria took place in 1906. The tour was organized by Japan’s leading daily newspaper, the Asahi Newspaper Company. With an eye on selling more newspaper subscriptions, the Asahi Newspaper Company ran an advertisement for a cruise to the great battle sites in Korea and Manchuria that had previously been featured in best-selling postcards, silk prints, and photos. The first announcement recruiting passengers for the “Cruise Touring Manchuria and Korea” appeared in the Asahi June 22, 1906 edition of the newspaper. And just three days after making this advertisement in their newspaper, the company had sold out all three classes of cabin tickets. In total, some eighty passengers were booked for the trip.

Following the success of this tour in 1906, subsequent discount tours were sold out in large numbers. This initial event gave birth to education packaged tours from Japan to Korea.

By the late 1910s, there was a growing demand by the millions of customers and potential customers to know more information about Korea. Japanese transportation companies like the Colonial Government Railways Company (CGR) joined forces with JTB to produce and distribute large numbers of detailed guidebooks, maps, train schedules, and picture postcards that captured scenic destinations, Korean people, and Korean customs. These items were sold at ticket offices at major piers, railway stations, and department stores in various cities like Tokyo, Seoul, Jijong, and Taiwan.

Most of this tourist information and items, even though they were produced using various publishers, were generally pretty uniform. Overall, this material tended to be modeled on an earlier generation of Victorian-era handbooks for Japan penned by foreign advisers, educators, and experts that were hired by the Meiji government. Typically, the first chapter of any guidebook from this time period covered what was considered essential travel information such as a JTB office, hotels, transportation links, fares, banking, customs, and post offices. An introduction would also include an overview of the land such as topography, population, history, and climate.

Also included in the guidebook would be a map insert, schedules for ships, trains, and transfer information. And since most passengers arrived by ship docking in Fusan (Busan) from either Osaka, Kobe, or Shimonoseki, the first place that was recommended on any itinerary from Fusan (Busan) was Taikyu (Daegu) along the Keifusen Railway Line (Seoul/Keijo to Busan/Fusan).

As for the main section of the guidebooks, they would typically cover major scenic, cultural, and business destinations for Japanese travelers found at major cities in Korea along the Colonial Government Railways Company (CGR) lines, as well as side trips to various destinations along the seaside, hot springs, and resorts that were linked by buses or shuttle services. More specifically, city tours like those in Seoul (Keijo) were planned as half-day excursions beginning at the Chosen Jingu (Main Shinto Shrine in Seoul on Mt. Namsan) and included Namdaemun (South Gate), the Botanical Garden and Zoo, the Chosen Sotokufu headquarters building (CGK), and the CGK Museum that was located at Gyeongbokgung Palace, as well as the Fine Arts Museum at Deoksugung Palace.

As for the appendix of several guidebooks from Japan, it was largely represented by major advertisers. Since businesses like tram and taxi companies, inns and hotels, pharmacies and resorts were largely owned and operated by the Japanese in Korea, it made sense that they would also attempt to advertise their own business directly to the consumer; namely, Japanese tourists.

Tourism Guidebook Photography and Illustrations

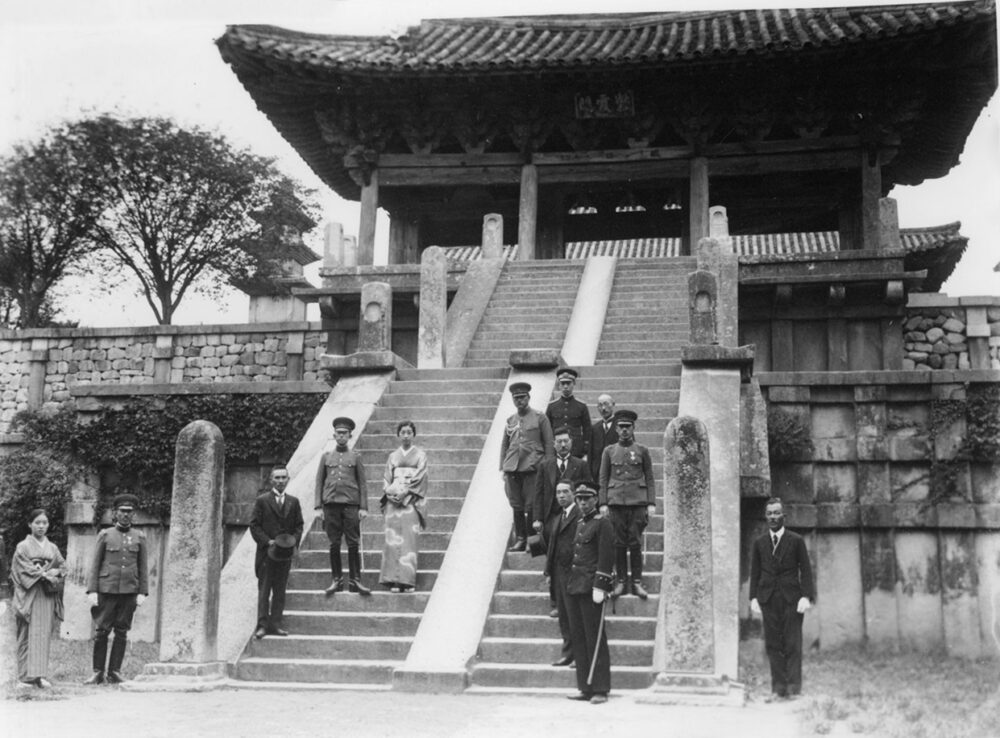

A typical layout of tourist photos and illustrations in guidebooks, postcards, and photo albums juxtaposed images of “old Korea” with “now” images of Korea. The former category identified the old Korea with old customs and traditions through grainy black-and-white photos. In these “old Korea” photos, you’d find Korean women engaged in everyday chores like washing clothes in the river, ironing at home, or carrying jars on their heads or children on their backs. And Korean men were seldom portrayed in these “old Korean” photos. However, if they were, they were typically street vendors, rickshaw drivers, or old yangban noblemen relaxing or smoking in their distinctive black traditional hats.

These “old Korea” images were contrasted with “new” Korea images featuring recently constructed modern colonial structures built by the Japanese. Examples of these can be seen in public works buildings, the CGK headquarters, banks, post offices, museums, train stations, schools, and hospital. This was also the case for archaeological or temple work that contrasted the dilapidated former structure with the recently renovated or rebuilt Japanese efforts on the old Korean structures contrasting Japan’s efforts with the way that Korea had long neglected their most treasured of structures and/or sites.

An example of Bulguksa Temple before and after Japanese efforts. The picture on the left is of Bulguksa Temple in 1914, and the picture on the right is from 1935. (Both pictures courtesy of the National Museum of Korea).

This visual methodology was a tried and true method of contrasting the old (bad) with the new (good). This strategy was employed in a variety of manners by the Japanese beyond guidebooks like in CGK controlled media, daily newspapers, and school textbooks. All of this was done to show the success of Japan’s “civilizing mission” on the rest of the world and especially on the Korean Peninsula. Furthering this visual propaganda was supplemental material that explained the inseparable nature found between Koreans and the Japanese from the beginning of time. Here’s an example found in print from the CGR during the 1930s:

“From the time of Empress Jingu’s conquest [ca. 3rd century] of the Three Han (Sankan), Chosen is the country that has had the closest relationship with our nation, a tie that can never be severed. On a clear day, one can see the mountains of Fusan in the country of Chosen across the sea. It is now only an eight-hour trip across the ocean from Shimonoseki on a boat that leaves morning and night. From there, one can transfer onto a train. In olden times, Kangoku [Korea] was formerly an independent nation, but in August 1910 it was incorporated into the empire. Since then the Chosenjin have become our brethren for all time to come. Since our races have merged again just as in ancient times, the future prosperity and happiness of our respective countries depends on forging very close ties, just as in olden times [mukashi] when Mimana [the ancient Gaya Confederation] was our colony. . . . Now anyone can travel in Korea and experience the same beauty and level of convenient service as we do in Naichi [Japan proper], since there is now no difference between Korea and Japan. This is the way it should be, since we are now one with many of our citizens. For students joining group tours, we wanted them to see in one glance what a warm and peaceful nation the land and people of Chosen are. Though there has been some misunderstanding in the past, in fact we are now one and the same people, as proven by the many research investigations that have been carried out by our scholars. Our nation is very concerned about the future destiny of the Chosen people, and we believe that the development of Chosen is also our happiness. So our great mission is to bring future happiness to Chosen as well as the eternal prosperity of the whole empire.”

To further reinforce this point, the archaeological “rediscovery” of Japan’s antiquity in the form of excavated sites of beautifully restored Silla temples and tombs found in Japanese photography was the most tangible evidence for the supposed common ancestry both racially and culturally. As such, the colonial travel industry played a large part in promoting this “nostalgic” image of Korea as a lost and poor country, whose shared cultural and ethnic past, was being restored to prominence once more through the superior Japanese and their “enlightened” government.

Popular Destinations for Japanese Tourists

By the late 1930s, JTB operated out of Minaki, which was the largest department store chain in Korea. In total, JTB had seven outlets in the cities of Seoul (Keijo), Busan (Fusan), Daegu (Taikyu), Daejeon, Pyongyang (Heijo), Hamhung, and Wonsan. JTB had two additional outlets at Hwashin department store (formerly at Jongno First Street) and Mitsukoshi (now Shinsegye), which was located in Myeong-dong across from the Bank of Chosen. Placing these ticketing outlets at major department stores was completely strategic. JTB was attempting to cater to the upper-class (both Japanese and Korean), who visited these shopping locations and presumably had money to spend.

As for popular destinations for these tourists, the southeast corridor of the Korean Peninsula was especially popular including Gyeongju (Keishu), Busan (Fusan), and Daegu (Taikyu). These three cities were prominently displayed in several tourist guidebooks and pamphlets. For example, both Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Hermitage were the two largest multi-year architectural reconstruction projects conducted by the Japanese and supervise by Sekino Tadashi (more on him later in future posts), who was a professor in the Tokyo University Architecture Department. He would supervise the Chosen government’s construction engineers between 1912 and 1930. And by the 1930s, the restored ruins of the ancient capital of Silla, Gyeongju (Keishu), and the newly built Gyeongju (Keishu) museum in central Gyeongju alongside Silla royal tombs, became the favourite destination for photography by Japanese tourists, foreign dignitaries, and amateur archaeologists.

Another popular destination for Japanese tourists was Pyongyang and Kaesong in the northwest corridor of the country. Typically an itinerary to this area included Kija’s Tomb, Manwoldae (Goryeo-era palace remains), and the Great Tomb of Gangseo painted tombs. Also of particular interest was the Nangnang Tombs (Rakuro). These were the restored tombs of the Han Dynasty, and they were touted as especially significant as the earliest “scientifically” excavated tombs in Asia, since no intact tombs dating back to the Han Dynasty (2nd century B.C. to 2nd century A.D.) had yet to be identified in China.

Yet another popular tourist destination in Korea was the southwest corridor. It was here that the Baekje Kingdom (Kudara) capitals of Buyeo and Gongju were located. And with Baekje archaeological discoveries of tombs, pagodas, and temples in the 1930s, this area became popular with both tourists and amateur and professional archaeologists.

The only tourist area that was far away from any commercial cities and sites was the historic Mt. Geumgangsan (Kongosan), which are known as the “Diamond Mountains” in English. The mountains have long been a popular destination for Koreans throughout history, and they are also known as a place that houses numerous historic Buddhist temples, as well. According to one Japanese tourist, the mountains were “the most spectacular natural beauty under the heavens.” As a result, the mountains were featured on CGR posters and magazines. Images of Mt. Geumgangsan were also heavily illustrated in magazines written in German and English for European consumption. From this promotion, and the mountain’s long history of being a desirable destination for hiking and religious retreats, the CGR built two mountain resorts. One was built at the Onjong-ri Station in 1915, and the other was built near Jangansa Temple in 1924 deep in the mountains as a hunting lodge and hot springs resort. It should come as no surprise then that during the 1930s that mountain climbing was the most widely advertised leisure activity. And the way that it was promoted was as a way to train one’s mind and body.

Other than Mt. Geumgangsan, other mountainous destinations that were popular in Korea for the Japanese, and especially for hikers, was Mt. Baekdusan and Mt. Jirisan. These regions were also popular for hunters looking for large game that were unavailable in Japan like tigers, bears, and wild boar.

As for nightlife in Korea’s major cities, the most often recommended choice for entertainment was hiring either Korean or Japanese female entertainers like geisha, or gisaeng in Korean, to “dance and sing for you.” In the JIR’s 1926 guidebook, it was written that “Geisha may be hired at anytime, anywhere, the charge of the dance depending upon the reputation and number of dances.” There was a high demand for these types of entertainers. In fact, it led to the establishment of a “School for Gisaeng” (Gisaeng Hakgyo) in Pyongyang. This school offered a curriculum that focused on musical instrument playing, dance, and popular songs of the day that could be sung in both Japanese and Korean according to the JTB of 1939.

Conclusion

There were numerous reasons as to why Japan so heavily promoted tourism in Colonial Korea (1910-1945). Some of these reasons were based upon geography, while others focused on commerce, infrastructure, and business. Some even focused on leisure. However, all of these efforts centred on the primacy of the needs and wants of the Japanese people over any and all of their colonies including Korea. All efforts, including tourism, were an after-thought to the expansionist war efforts of the Japanese government. Tourism was successfully presented in a number of ways that affected every corner of the Korean Peninsula, which helped to fund Japan’s war efforts. One way that tourism was successfully promoted to the Japanese people was through the rebuilding and renovating of Korea’s religious and cultural past in the form of Korean Buddhism. Temples and temple sites were highly popular with the Japanese. And one of the most popular sites, for obvious reasons, was the city of Gyeongju, which is home to both Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Hermitage. At the very heart of tourism, besides money, was a nostalgic “return” and “reunion” of the Korean and Japanese people. And the Japanese bought it up through their tourist yen. However, by 1943, the tourism industry in Colonial Korea collapsed; and just two years later, Imperial Japan would fall, as well.