Colonial Korea – Archaeology in Korea

Introduction

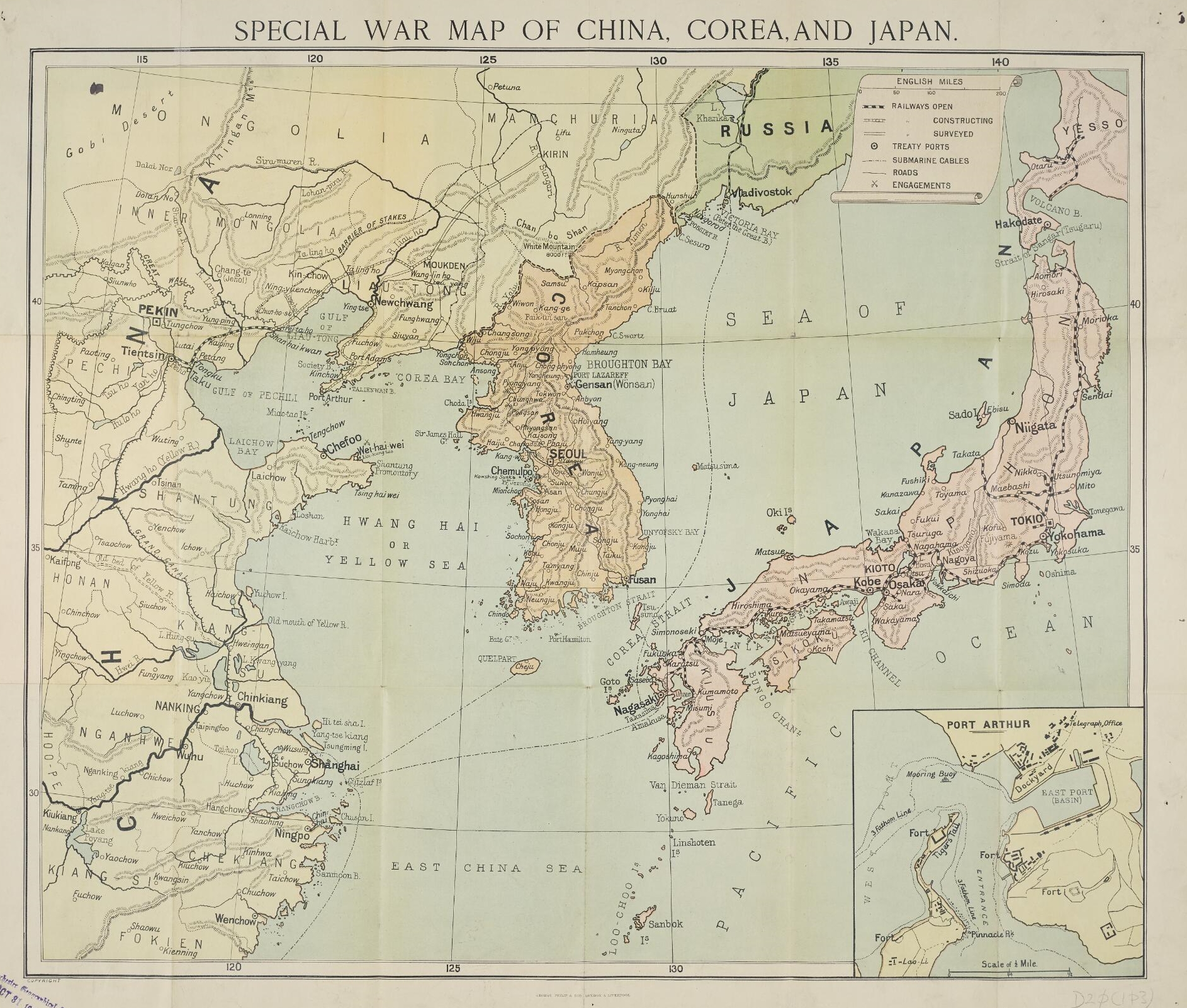

Before Japan even occupied the Korean Peninsula, they took preliminary steps towards the colonization of Korea. One of these steps by Japanese scholars was to survey the customs, products, and cultural assets of Korea. Even at this time, it’s completely plausible that the Japanese already had the goal in mind of expropriating Korean cultural assets back to Japan. But before doing this, they needed to map the Korean Peninsula to fully appreciate what awaited them in their conquest. With all of this in mind, the Japanese thoroughly investigated, charted, and mapped Korea’s historical assets and sites. And because of Japan’s shared religious and cultural heritage found in the form of Buddhism, the Japanese did an exhaustive search of the future colony.

There were numerous reasons as to why the Japanese would do this. One of these reasons for all of this archaeological work was to portray the Korean colony as inferior to Japan. Another reason was to justify the annexation of Korea through tourism and conservation that had previously been overlooked by the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). And finally, the other link that the Japanese attempted to form through these archaeological endeavors was to form a bond that united the two people through a form of pan-Asian Buddhism to help combat Western and Christian influences. And through decades of work, Japanese scholars, governmental agencies, and archaeologists attempted to make this a reality.

The Examination of Korean Historical Relics and Sites

After the annexation of Korea in 1910, the Japanese set about systemically organizing and investigating various cultural assets and sites throughout the Korean Peninsula. The Japanese had used this same investigative approach on their own ancient temples and temple sites between 1888 and 1897. By continuing the same methodology, but this time on Korean temples and temple sites, Japan was attempting to demonstrate the continuity found between Korean and Japanese cultures and their pasts. And that this connection stretched all the way back to “time immemorial.”

It was through Japan’s own surveying experiences of their own national cultural assets that gave its leaders confidence in investigating the cultural assets of the future colony of Korea. And while the motivation behind the surveying of the two nations were different, the Japanese applied their own classification methods to examine the cultural assets of Korea. What’s interesting about this methodology is that Japan assigned a previously unused approach to the functions and roles of the cultural assets. Instead of being oriented through the prism of religious importance and significance, these Korean cultural assets were now considered as “art” and “relics” from Korea’s past.

One of the central figures to this exploitive exploration of Korean historical relics and sites was Yagi Sozaburo (1866-1942) of the Tokyo Imperial University. Yagi Sozaburo was sent to Korea from the Department of Anthropological Studies at Tokyo Imperial University. This department had been first established during the Meiji era (1868-1912). Specifically, Sozaburo’s fieldwork was based in Gyeonggi-do Province between 1893 and 1910, where he surveyed the dolmens from ancient Korea and the tombs that dated back to the Three Kingdom through to Unified Silla (so approximately 300 to 935 A.D.).

Following Sozaburo was Sekino Tadashi (1867-1935), Torii Ryuzo (1870-1953), and Kuroita Katsumi (1874-1946). All three continued the surveys under the direction of the Japanese Government General of Chosen (Korea) and different Japanese prefectural offices. It’s important to note all of these surveys because they were the very first surveys of Korea’s cultural assets and historical relics.

Sekino, Torii, and Kuroita Katsumi specifically surveyed and ranked various structures and historical sites. They also classified ancient Korean tombs under the jurisdiction of the Japanese provincial government offices of the Government General of Korea. In turn, the Government General issued the “Korean Temple Ordinance.” This would help manage the merging of temples, the transferring of a temple’s cultural assets, as well the various assets of temples like land.

In 1916, the Government General published the “Regulations on the Preservation of Ancient Tombs and Relics.” This was the first guideline that would help instruct people on the preservation of historical relics. This total framework allowed the Japanese to manage and supervise temples and their assets. It also allowed for the surveying and preservation of historic sites. And the Japanese would also manage museums on the Korean Peninsula. According to the Japanese historian Fujita Ryosaku (1892-1960), Japan regarded these archaeological undertakings as its proudest legacy in Korea.

By 1921, and through the discovery and excavation of the Tomb of the Golden Crown, or “Geumgwanchong” in Korean, in Gyeongju, the control over the preservation of ancient temples and historic buildings was transferred to the Department of Archaeological Research of the National Archives Bureau, which was under the Japanese Government General.

With these organizational efforts, the Japanese colonial government was able to more thoroughly, as well as professionally, research historic sites in colonial Korea. It was viewed by the Japanese that the restoration, repair, and preservation of the Korean Buddhist temples, after they had been fully investigated, formed part of the social enlightening of the Korean masses by the Japanese imperialists and their ideology. This was all done under the guise of “cultural politics.” By being able to weaponize Korea’s past, they could use it as an instrument to control and influence modern Koreans and their culture.

The History of Korean Buddhist Artifacts

Before Japan had colonized Korea and converted Korea’s Buddhist artifacts into pieces of “art,” Korean Buddhism endured a lot throughout the Joseon Dynasty. Historically, Korea endured two devastating wars during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). The first of these two wars was the extremely destructive Imjin War (1592-1598). The second of these two wars was the Qing Invasion of Joseon (1636-1637). Because of these two wars, Buddhist rituals for the dead were actively conducted in Korea despite the Joseon governmental persecution of Buddhism. Both native governmental policies and foreign led wars on the Korean Peninsula destroyed Buddhist temples and their properties like statues and paintings throughout the peninsula. But without temples, Koreans, who didn’t rely on Confucianism for memorial service; but instead, relied heavily on Buddhism with the afterlife, couldn’t hold proper memorial services for the dead through such services as the Water-Land Ceremony, which is known as “Suryuk-jae” in Korean.

With all of this in mind, and with the ending of hostilities, temples were rebuilt and new statues and paintings were enshrined in the newly built temple shrine halls. In fact, during the first half of the 17th century, recent research has revealed that over 200 statues were produced at this time using various materials and sculpting techniques. These temple rebuilds and production of temple statues and paintings lasted up until the 18th century. After this productive period, most renovation efforts were curtailed and focused more on repair like the re-colouring of Buddha and Bodhisattva statues. Yet despite the downturn of renovations, the demand for memorial services continued to increase at temples.

In a twisted sort of way, and because of the marginalization of Buddhism during the Joseon Dynasty, Buddhism started to regain their popularity in society as the main religion of the people because of the suffering inflicted by the two late 16th and mid-17th century wars. Because Buddhism was capable of healing the trauma caused by the wars through ceremonies, and because of the defence of the nation by the Righteous Army, the dominance of the pro-Confucian government started to gradually weaken. And in its place, Buddhism started to reassert itself from the margins of Joseon society.

It was to this that Koreans started to imbue these Buddhist objects of worship and the ceremonies that surrounded them with hope. As a result, these objects of worship took on an elevated meaning of good fortune for the future. And it was these religious artifacts that the Japanese would predominantly encounter with their annexation efforts that centred around Buddhism and the religious past that they held in common with Korea.

Korean Religious Artifacts Become Japanese “Art”

Following the Japanese annexation of Korea, Korean Buddhist art was quickly incorporated into the category of “Korean art history” through the surveys conducted on temples, pagodas, and artifacts throughout Korea. The reason for this change is that Japan was following the model set forth by Western nations and their colonizing efforts. As such, and as part of this effort, art history was a field of Western scholarship that the Japanese learned and employed during their occupation of Korea. One way that the Japanese did this was by surveying the material cultural heritage of Korea and then organizing these items into a chronological order.

After these organizing efforts, Japanese scholars gave lectures on Korean art history not only to the Japanese but to Korean, as well, to help separate the religious from the items. In turn, the religious meanings were extricated from these Buddhist items so as to stand alone as a piece of “art.” The term “Korean art history” was first coined in a report entitled “Research on Korean Art” by Sekino Tadashi in 1910. This newly used term “art” for these items first emerged in German-to-Japanese translations in Japan in 1872 to describe Japan’s cultural assets. This concept of “art” was then applied retroactively to all forms of material cultural assets in Japan. This term used on Japanese material cultural assets were then transferred onto Korea’s material cultural assets by the Japanese. And the term “art” was applied to any item that was deemed suitable enough to be considered as “art.” There was simply no definitive definition for what qualified as “art.” As such, Buddhist cultural assets, whether they were Japanese or Korea, were included in this new category and the separation that was to form between the religious and the aesthetic were made.

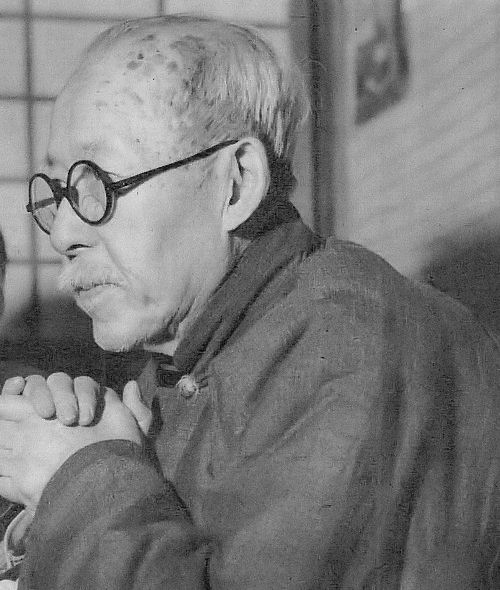

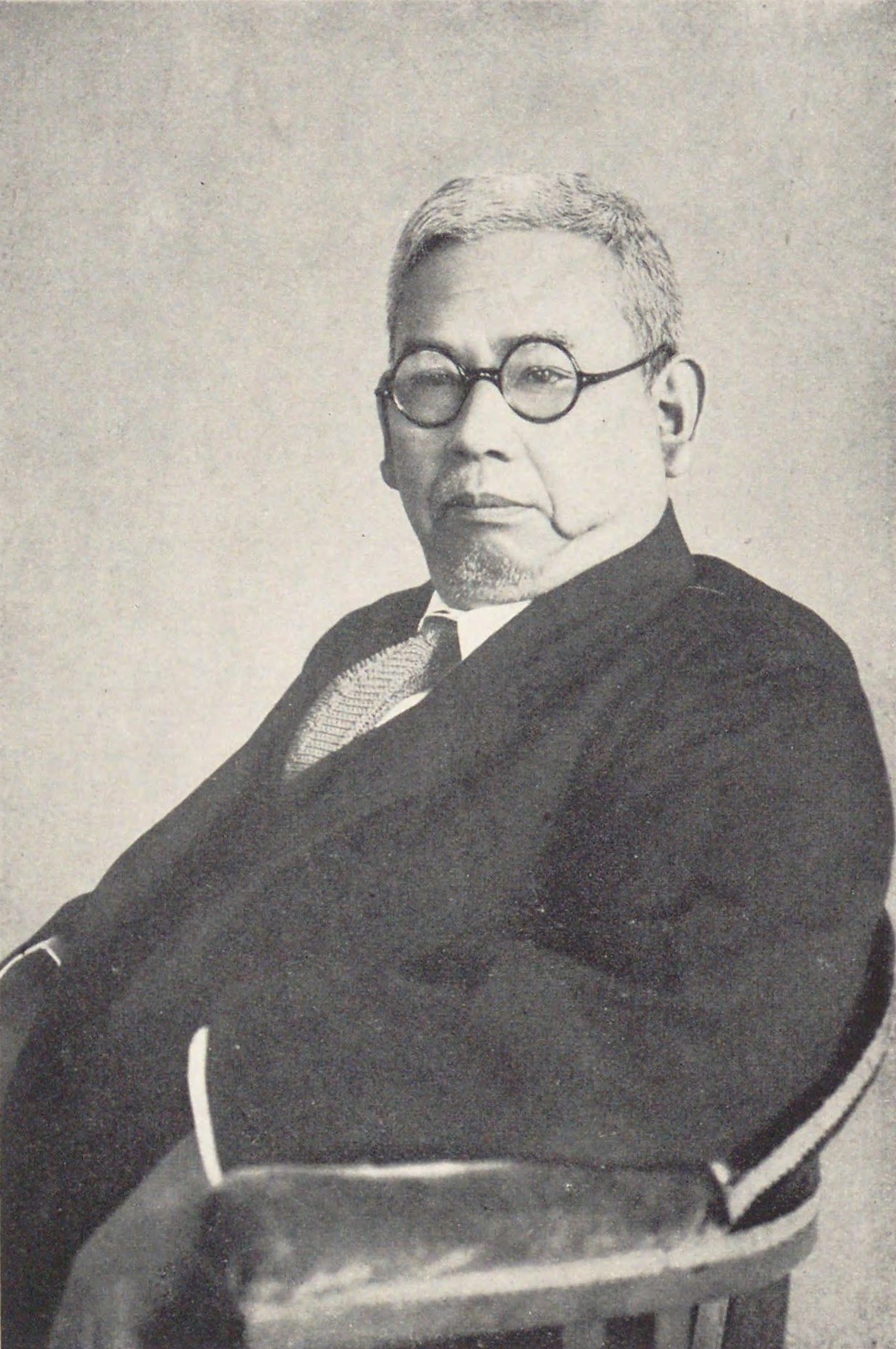

Starting in 1902, Sekino Tadashi, who was a professor in the Department of Building Houses at Tokyo Imperial University, first surveyed the cultural assets of Korea. He examined both ancient buildings and the relics of the Joseon Dynasty. Afterward, Sekino published his findings in the “Brief Report on the Investigation of Korean Architecture” in 1904. In this report, each of Korea’s provinces was surveyed. And while these provinces were examined regionally, the Korean cultural assets were organized in historical order. This system followed a system already established by Japanese art history; and more specifically, by Okakura Tenshin (1863-1913) and Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908). This type of system helped outline the rise and fall of a dynasty and based a dynasty’s artifacts according to this time period.

After Sekino published his report, he then gave a lecture on the topic entitled, “On the Transitions of Korean Art,” which was given in 1909 at the Gwangtonggwan Building in Seoul. This lecture was published under the title, “Red Autumnal Leaves of Korea.” And it was the first official publication on the subject of Korean art history. This work included several cultural assets of Korea including those from Unified Silla like the three small bronze Buddha statues, the Stone Brick Pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple in Gyeongju, Dabotap Pagoda of Bulguksa Temple, the stone lantern of Bulguksa Temple, and the Gilt-Bronze Standing Bhaisajyaguru Buddha of Baengnyulsa Temple. Also included in this work were assets from the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), as well, like the thirteen-story pagoda of Bohyeonsa Temple on Mt. Myohyangsan, the incense burner from Cheondeungsa Temple, and the portable shrine from Yeongmyeongsa Temple. There were only a few items of Buddhist art from the Joseon Dynasty in this book. One of these assets was the thirteen-story marble pagoda in Gyeongseong, the Buddha statue inside the main hall at Bohyeonsa Temple on Mt. Myohyangsan, and the Buddha statue from inside the Eungjin-jeon Hall at Seongbulsa Temple on Mt. Cheongbangsan.

The Korean “art” that Sekino mentioned in this book consisted mainly of various forms of Buddhist art from bells to pagodas, to statues and incense burners. Although the book is primarily a list of names of objects, the text does describe how Buddhist cultural assets were newly included as pieces of “art,” shedding their religious meaning. Until this time, no one had yet to regard these Buddhist cultural assets as objects of aesthetic appreciation as “art.” While Koreans during the Joseon Dynasty definitely appreciated the aesthetic like in landscapes and poetry, oftentimes from Buddhist temples, they didn’t define or even attempt to define them as anything outside their functionality as a Buddhist object. As such, Sekino’s lectures and books were the first attempts at creating space between the origin of their Buddhist functionality towards a more aesthetic item. Buddhist temples used these items for rituals and ceremonies. Sekino and the Japanese wanted to appreciate these items in a whole new light. It was from this moment in time that people came to appreciate these Buddhist cultural assets as objects of “art.” A new context and narrative had been formed. The Buddhist objects now existed on two plains: one of worship and one of aesthetics. And for the Japanese, they were moving away from the religious so as to possess them in their own terms. These new terms and the redefining of these objects as “art” gave these objects a different value. As such, these objects of faith and worship now had a previously unintended meaning from their original construction. This re-centering was brought forth by a new political climate. Due to Sekino’s writings and lecturing, Korean Buddhist material now acquired the stature of being “art,” and these items no longer held the Buddhist foundation that they formerly had when they were first created. The religious was separated from the religious object to create an object of “art.”

With this as orienting point of departure, the history of Korean “art” gradually expanded through the further surveying and excavation of temples and Buddhist sites throughout Korea from Sekino’s efforts. In 1923, more than ten years after the publication of “Red Autumnal Leaves of Korea,” Sekino launched a series of lectures on the topic of Korean art history at the request of the “Korean Historical Society.” Ten years after this, Sekino would publish “Korean Art History.” The series “Illustrations of Korean Antiquities” was published between 1915 and 1935, and it played a central role in Sekino’s writing “Korean Art History.” “The Illustrations of Korean Antiquities” introduced the material cultural assets and artifacts from Korea’s prehistoric period up to the Joseon Dynasty, arranging all of these artifacts in chronological order.

The Restoration of Buddhist Art by Japanese Scholars

After investigating Buddhist temples and their art, which were classified as “cultural facilities” by the Japanese, the Japanese scholars then attempted to restore and preserve these assets. The restoration of these cultural assets by the Japanese during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945) was motivated by political calculations. This was different than previous restoration efforts on these Buddhist assets. While Koreans had previously restored these temples and their art for religious reasons like accruing good karma, the restoration work conducted by Japanese authorities was far more practical. Instead of being religiously oriented, the efforts to restore these items was done to justify Japanese colonialism. The religion of the Korean people was secondary to the Japanese authorities’ efforts and how they defined these efforts.

To put things in context, starting in 1876 following the Meiji era, Japan carried out a large-scale survey of their own ancient temples. This was done to push for a separation between Shintoism and Buddhism; which, until that time, had been fused together as one religious entity throughout the course of Japanese history. Unconcerned with the separation of these previously inseparable religions, the Meiji government went ahead with it anyways. As a result, the Meiji government classified the related religious assets as forms of Japanese art in the name of modernizing the religions. No longer were these religious items categorized under their original religious meanings. Instead, they were now Japanese cultural assets and not Buddhist or Shinto. It was with this same rubric that Korea’s Buddhist cultural assets fell under, as well, eventually.

The surveying and changes in restoration goals in Korea would lead to the restoration of Korean Buddhist cultural assets. Initially, the Japanese government hadn’t planned to restore Korean artifacts when they were surveyed. However, at the time of Sekino’s initial surveys starting in 1909 such items as the Stone Pagoda at Mireuksa Temple Site in Iksan, Jeollabuk-do; the Haetalmun Gate of Dogapsa Temple in Yeongam, Jeollanam-do; and the Five-Story Stone Pagoda at Seonggeosa Temple Site in Gwangju had already been classified as “artifacts requiring urgent repair work.” So it was with this initial momentum that the Japanese would continue their efforts through the proceeding years.

The Reason for Japanese Archaeological Efforts

Most of Japan’s restoration work took place in the 1920s before the entire world would erupt in war. The Japanese imperial government put forth a significant effort through the concentration of resources to repair and restore Korea’s more prominent Buddhist cultural assets like Seokguram Hermitage in Gyeongju. The cost of the first round of repairs on Seokguram Hermitage that were performed on the site up until 1915 totaled some 22,726 won (or about 450 million won/400,000 USD in 1998; which as of 2023 is some $727,000 USD).

Specifically, the reason why the Japanese invested so much in the repair of Seokguram Hermitage in 1913 was for propaganda purposes. This work was conducted by the Department of Civil Engineering within the Ministry of Internal Affairs. This was not only so that the Japanese could distort and misrepresent history for colonial purposes, but the Japanese also did this to help justify the annexation of Korea in 1910. By repairing Seokguram Hermitage and its famed grotto, Japan could point to something tangible that could highlight the successful efforts of colonial rule on the Korean Peninsula. More plainly stated, Japan could point to Seokguram Hermitage and indicate that their efforts were not only helping to secure Korea’s tangible past but that Japan was also helping Korea modernize, as well.

These repairs and restorative work were then carried out on artifacts across various regions in Korea. However, among these efforts, most of this work was concentrated on Silla Buddhist artifacts and sites in the Gyeongju area. Another reason that the Japanese focused their attention on these Buddhist monuments and artifacts from Gyeongju is that they believed that these works were similar to those found in Kyoto. This similarity, in the eyes of the Japanese, would help to develop and drive tourism in Korea; and more specifically, in Gyeongju.

The reason for this is that these restorative acts on Buddhist artifacts and sites were in line with the Japanese thought that “Buddhism was the core of the Eastern Spirit,” which was an idea pursued by the Japanese since the Meiji era (Jan 25, 1868 – Jul 30, 1912). Additionally, it was the cultural assets of Korea that the Japanese placed the greatest value upon, which were created before the Joseon Dynasty. The reason for this is that the Japanese were attempting to evoke in the minds of Koreans the memory of cultural achievements founded during the “Buddhist era” that predated the Joseon Dynasty. Japan needed to point to a pre-modern era that predated the “ruin” of Korea. This “ruin” had been brought on by the rulers of Joseon. The glory of Korea lay in its distant past that had flourished when Buddhism was at the very heart of its society and its successes. So it made sense to attack Joseon rule, while elevating what came before it. It fed into the narrative that Japan had to promote Buddhism which linked the two people together.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Governor General of Korea took great pride in Japan’s achievements in colonial Korea. As such, they presented copies of the “Illustrations of Korean antiquities” to visiting foreigners. Inside this text, it was common to present two side-by-side photos of the “old” (bad) Korea with the “new” (good) Korea under Japanese Colonial rule. This was an old tried and true method conducted by several colonial powers on the colonized to help justify colonization.

What should be noted at this point is that it’s impossible to determine whether the new form of these Buddhist cultural assets retained the original configuration and composition of these works after Japanese scholars, archaeologists, and technicians had completed their work. There are simply no resources that one can look at to confirm or consult the original appearance or layout of these cultural assets. As such, there is no way to know if the Japanese were in fact restoring these assets of material culture to their original form or simply a Japanese interpretation of what they should have looked like.

It should also be noted at this point, as well, that prior to Japanese occupation, the Joseon government had yet to conduct a national survey of the cultural assets of the nation. Instead, it was during the Japanese occupation of Korea that acted as a catalyst for the acceleration of the surveying, restoration, and maintenance of these Korean Buddhist cultural assets. Part of this is due to the anti-Buddhist policies of the Joseon Dynasty and the other is cost. In a strange way, the Buddhist cultural assets that have come to embody Korea’s cultural heritage today are based upon the data collected during these surveys and restorative efforts by the Japanese.

Conclusion

The “re-discovery” of the significance and importance of these Korean Buddhist cultural assets was promulgated by the Japanese themselves through lectures and publications. And one of the reasons that the Japanese made such claims was to put Buddhist cultural assets at the very centre of Korea’s cultural heritage. By doing this, they hoped to link the idea that Buddhism was at the very core of the Asian spirit. This was done for a number of reasons by the Japanese, but the primary reason, arguably, was to combat the growing influence of Western thought and Christianity. Japan hoped that by elevating not just Korean Buddhism, but all Asian nations that fell under its sphere of influence, that Japan could create a pan-Buddhism that could and would resist outside influences in the form of Western thought and Christianity. It also didn’t hurt that it would help justify and subsidize the war efforts in other parts of Asian. This was done in numerous way; but arguably the most effected was tourism and both the revenue it produced and the cultural bond it formed through Buddhism.

One of the core arguments that the Japanese emphasized at this time was that Korean Buddhist art was excellent. And the reason for the Joseon Dynasty’s collapse was the rejection of Buddhism. As a result, the Joseon Dynasty was in decline. Though Baekje, Goguryeo, Silla, and Goryeo had produced fine pieces of Buddhist art that were cultural assets, they had been reduced to rubble over the past 500 years of Joseon Dynasty rule. And so the argument goes, it took the Japanese, through their colonial powers, to help resurrect these cultural assets that had long since been neglected. And through these repairs and renovations, the Japanese colonial government in Korea had resuscitated the Buddhist cultural assets and elevated them to piece of “art” in contemporary Korea that could be enjoyed in the present. With this change, Korean Buddhist assets were assigned a new role. And with this new role, a greater number of people, whether they were Korean or Japanese, could appreciate these “re-discovered” pieces of “art.”