Colonial Korea – Buddha’s Birthday

Introduction

At the end of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), and with the growing influence of Japan and Japanese Buddhism on the Korean Peninsula, Korean Buddhist faced the double threat of the continuation of centuries of persecution and marginalization by their own government and having their own tradition hijacked and supplanted by a foreign tradition. It was to this that Korean Buddhists were faced with the choice of either modernizing or simply being replaced. It was to this dynamic relationship that would help modernize Korean Buddhism. As such, the re-traditionalization of Buddha’s Birthday, similar to the modernization of Christmas in the West, was a highly complex negotiation in and among Korean Buddhists about what their tradition meant, while also plying their way through the turmoil that faced both the final days of the Joseon court and the interference and influence that both Japan and Japanese Buddhism hoped to have over the Korean Peninsula. It was a tumultuous time of competing ideologies, both religiously and politically, which would partially find an outlet in the form of Korea’s Buddha’s Birthday Festival. This post will focus on Korean Buddhists ability to re-traditionalize a key facet of Korean Buddhism through the celebration of Buddha’s Birthday both before, during, and after Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945).

The History of Buddha’s Birthday in Korea

In Korea, Buddha’s Birthday was traditionally the highlight of the annual Buddhist ceremonial calendar. It was celebrated with lighting lanterns, reading sutras, and inviting both monks and lay-people for meals at temples. The Buddha’s Birthday was just one of several festivals held by Korean Buddhists in a year. And of these festivals, three were lanterns festivals.

These widespread Buddhist festivals started during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) and evolved over time. They were state-sponsored affairs aimed at unifying the country behind the king and his family so prayers for their welfare were made at these festivals and ceremonies. While the dates of various Buddhist festivals differed year to year because the state festivals were determined by the state, the Buddha’s Birthday was always on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month. The Buddha’s Birthday celebrations and festival in Korea would emerge near the end of the Goryeo Dynasty and be affixed to a specific date during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).

Because of the anti-Buddhist polices of the Joseon Dynasty, in favour of Neo-Confucian ideology, all but the Buddha’s Birthday festivals survived of all the various festivals that Korean Buddhist formerly held. However, while the birth of Buddha was at the very heart of this celebration during the Goryeo Dynasty and the earlier years of the Joseon Dynasty, the Neo-Confucian policies of the state quickly eroded the centrality of Buddha in Buddha’s Birthday celebrations. Instead of being the celebration of Buddha’s Birthday, the April 8th lantern festival would essentially become a holiday for children.

During these April 8th celebrations during the Joseon Dynasty, instead of celebrating the Buddha’s Birthday, they were transformed into public festivals both in major cities like Seoul, Pyongyang, and Kaesong. Lanterns were still lit and people would pray for the well-being of their families. They would also spend money to enjoy themselves in the commercial districts of these cities. Throngs of people would fill the streets, and the holiday would become a major shopping day; thus, further distancing itself from the original meaning of the April 8th festival. Toys would be bought for children and lanterns were bought to decorate homes. In a way, a quasi-Buddhist festival formed around this date during the majority of the Joseon Dynasty’s duration.

This would start to change, however, by late Joseon, with the increasing contact that Korean monks would have with other monks from various countries throughout the world. This would help Korean monks better understand their own position in their own country through the governmental policies of other countries towards international Buddhism. This comparison was especially heightened with the presence of Japanese Buddhist missionaries through the deepening involvement that Japan had in Korean affairs from the early 1900s onward.

This pre-colonial period, which saw an erosion of the dominance of Joseon Neo-Confucian policies, saw the Joseon government adopt a more tolerant policy towards Korean Buddhism. As quoted in the Korea Review newspaper from 1902, the Joseon government’s policy towards Korean Buddhism was “favourable to this cult [Buddhism].” And as such, Buddha’s Birthday at this time “was observed with considerable show,” which was an obvious nod to the encroachment and acceptance of Japanese policies and religion in Korea and the Buddhist ideology that was closely linked to Japanese nationalism.

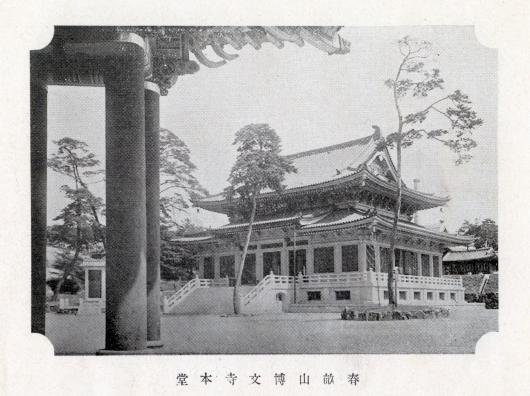

This 1902 ceremony referenced above by the Korea Review newspaper was confined to the temple complex of Wonheungsa Temple, which would come to be known as Gakhwangsa Temple; which, in turn, would come to be known as Jogyesa Temple in central Seoul. However, while it was restricted in Korea, Korea’s participation in this ceremony was part of an international attempt to place Buddha back at the centre of Buddha’s Birthday celebrations. This would be part of the rise of pan-Asian Buddhism that would help link Japan to Korea through the Japanese colonial government (1910-1945).

By 1913, this celebration had grown so popular at Gakhwangsa Temple that tickets needed to be issued to limit those that could attend. Also at this time, similar ceremonies were being conducted outside of Seoul, as well, that were also popular. In fact, a Christian missionary reported in 1907 that some eight thousand Buddhists visited temples in the Mt. Kumgangsan region (modern-day North Korea) of Korea to celebrate the birth of Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha).

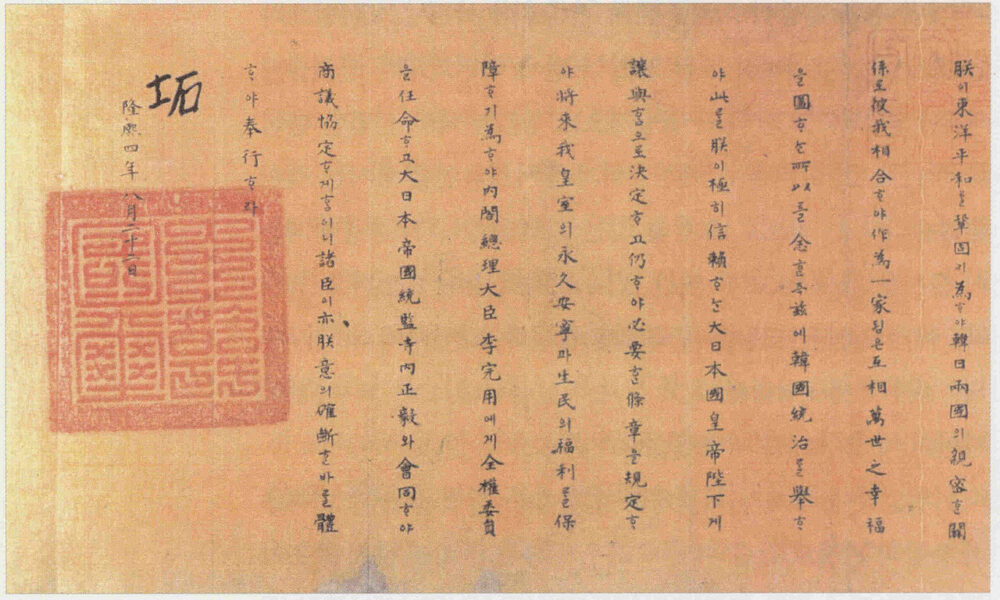

All of this was a prelude to Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945). With the growing acceptance of Korean Buddhism by the Joseon government, as pushed and promoted by the Japanese government to create a common link between the two countries, the acceptance of Buddhism that was once marginalized during Joseon rule would continue to expand.

After the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910, with Japan seizing power on the Korean Peninsula, Korean Buddhists, temples, and cities would expand this holiday under agreement with the Japanese colonial government. Through the Japanese, new roads and mass transportation were made for those that wanted to travel to Korean Buddhist temples. Even remote temples were made easier to get to through the modernization of roadways. Another way to help encourage people to travel during Buddha’s Birthday celebrations was that the colonial government also increased the number of buses traveling at this time, as well as discounting these tickets. This helped to further the popularity of these Buddhist Birthday events.

With transportation changing in Korea, the nature of the celebration started to change, as well. Even faraway mountain temples were influenced by multi-national sources like Sri Lankan Buddhism, Japanese Buddhism, and even Korean Christianity. These new elements included Buddhist hymns (versus Buddhist chants), musical performances on the life of the Buddha, and public Buddhist lectures (instead of Dharma talks that were restricted to Buddhist temples). Even the publication, translation, and distribution of the popular novel “Siddhartha” by Herman Hesse (1877-1962) in Korea was done, as well.

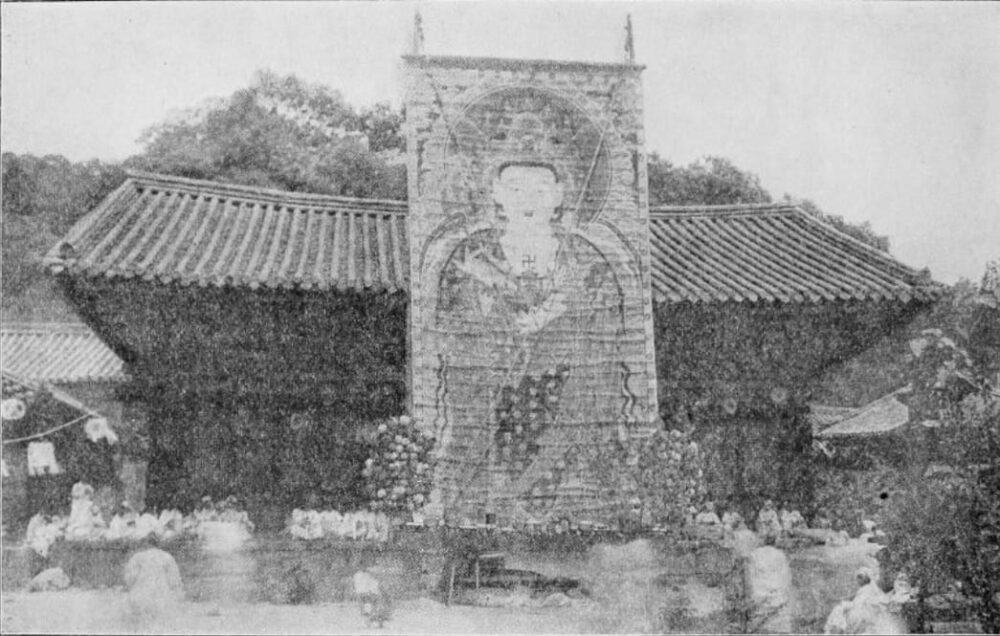

Perhaps one of the more prominent non-Koreans to explore the Korean Peninsula at this time was Frederick Starr (1858-1940), who was a professor of anthropology at the University of Chicago. Starr would visit Korea four times from 1911 to 1918. He would see first-hand the steady rise in popularity to the newest iteration of the modernizing Buddha’s Birthday celebrations in Korea. At this time, Starr would stay at different temples and interview the monks there. One of these visits was to Tongdosa Temple in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do in 1918 during Buddha’s Birthday celebrations. Here is a quote from his 1918 book entitled “Korean Buddhism”: “We were at Tongdosa on Buddha’s Birthday. It is one of the great monasteries of the South. They knew we were coming and therefore we found a place to sleep. When we were within three or four miles of it we found ourselves in a crowd of persons going up to the celebration. The nearest railway station is about ten miles away. Most of the people, however, had walked from their homes. It is a mountain district, sparsely settled; there are surely only two or three towns of any size within fifteen miles of the place. When we reached the monastery we found one of the liveliest scenes we ever witnessed in Korea. The head-priest told us that ten thousand people slept on the grounds of the temple that night. The majority of them were women…We were two nights there. On the full day that we spent with them a wonderful crowd of people was present; there were a few Japanese – a teacher and one or two officials – but apart from these the multitude was Korean. Probably fifteen thousand people were there that day. We found that one of the events of that evening was a moving-picture show in one of the monastery buildings. The life of Buddha was to be represented in moving pictures. All this does not look much like death! It is said that at the other head monasteries there were proportionately equal crowds.”

As Korean Buddhism entered the 1920s, and with the increased focus of Buddha now being the centre of Buddha’s Birthday celebrations, the Lantern Festival, or “Yeondeunghoe – 연등회” in Korean, gradually started to incorporate the Buddha back into the holiday. So it was by the 1920s that Korea’s native version of Buddha’s Birthday was back in place and celebrated nationally. And it was with this ongoing modernization of not only Buddha’s Birthday, but Korean Buddhism as a whole, that Japanese Buddhist turned their attention to attempting to alter the Korean Buddha’s Birthday celebrations with their own version: Hana Matsuri. This would be a challenge for the Japanese, especially since the modern Buddha’s Birthday celebrations had grown to be so popular, but it would be a challenge that the Japanese Buddhist would attempt to overcome.

Buddha’s Birthday in Japan – Hana Matsuri

Although Japan wasn’t under colonial rule in the late nineteenth-century, Japanese Buddhism suffered under the newly adopted and strongly anti-Buddhist policies that saw a new form of pure Shintoism freed from Buddhist influences. As such, this form of Shintoism, which sought the return of the pure Japanese spirit free of corrupting external influences (namely Buddhism), was promoted as the new state religion at the start of the Meiji era (1868-1931). In Japan, this state policy was known as shinbutsu bunri (separating Buddhism from Shinto). All of this religious nationalism was done to help combat the fear of Western imperialism and Christianity.

Initially, the Meiji government didn’t see Buddhism as a useful tool in helping to create a strong military and a robust economy in a modern Japanese society. At this time in Japan’s history, Buddhism was viewed as being archaic and superstitious, which was the opposite of what the Meiji government was intending. As such, the Meiji government adopted policies that intended to eradicate Buddhism and elevate Shintoism as the state religion. In turn, Japanese authorities attempted to modernize what was left of Japanese Buddhism by decriminalizing clerical marriage and the eating of meat. In the face of this adversity, Japanese Buddhist reformers attempted to modernize their religion and make it more compatible in an ever changing modern Japan. And one way they attempted to do this was through the celebration of Buddha’s Birthday.

In pre-modern Japan, Buddha’s Birthday was traditionally celebrated annually at temples just like it had been in Sri Lanka, China, and Korea. However, with the Meiji government in power, there were numerous changes that happened to this celebration including the very date of the Buddha’s Birthday. Due to Japan adopting the Gregorian calendar in 1872, the old lunar calendar date of April 8th was replaced. Instead of having a roving holiday, the new Japanese Gregorian calendar affixed the date of the Buddha’s Birthday to April 8th.

One of the first modern forms of the Buddha’s Birthday festival was organized by the “Young Men’s Buddhist Associations” (Shin Bukkyō seinenkai in Japanese, or YMBA for short) in 1892. During these early years of the festival, Buddhist groups were unable to unify their efforts to hold one large festival; instead, different university campuses and private institutes held their own separate events. In fact, in Tokyo alone, there were different festivals taking place at the same time but in different locations. And while some Buddhist priests did participate in these early festivals, these events were largely organized by youth groups without the backing of institutional Japanese Buddhism.

In an effort to help make the holiday more international and trans-sectarian, in 1902 the Japanese Buddhist youth groups invited non-Japanese Buddhist to these festivals like Indian students studying in Japan. By 1903, however, the efforts of these youth groups that were without the backing of official Buddhist organizations came to an end after eleven years.

In 1915, the Buddha’s Birthday festival resumed. At this time, Buddhist groups attempted to secure governmental funding and administrative support, but the Japanese government declined to participate. Because of this governmental cold shoulder, the festival’s organizers were far more assertive in their celebrations in 1916. This time, Buddhist priests from different sects joined together with various youth groups. Finally drawing together various youth groups and various traditional Buddhist sects, this newly formed group established the “Association of Hana Matsuri of the Tokyo Alliance.”

As for the name and adoption of Hana Matsuri for the new Buddha’s Birthday Festival in Japan, it dates back to 1901 in Berlin, Germany. There, the Japanese residents led by Anesaki Masaharu (1873–1949) and Chikatsumi Jōkan (1870–1941) organized an event for Buddha’s Birthday. According to Chikatsumi memoirs, the April 8th date for Buddha’s Birthday coincided with Easter (Ostern), which was April 7th in 1901. And because in Germany Easter is also called Blumenfest, or Flower Festival in English, Chikatsumi wrote, “The celebration dates for the two great religions of West and East happened to meet each other.” Chikatsumi, and a group of eighteen other Japanese that included scholars, diplomats, and army officials, dedicated to organize a special Buddhist Birthday festival and named it Blumenfest. And in Japanese Blumenfest translates as “Hana Matsuri.” When Anesaki returned to Japan, the new name for the festival spread quickly among Buddhists. So it’s in 1916 that the name for the Buddha’s Birthday Festival came to be known as Hana Matsuri, and it would come to be known as such, or “Hwaje” in Korean, when Japan decided to first introduce this festival to the Korean Peninsula in 1928.

With the advent of the newly galvanized Hana Matsuri in 1916, it brought about many modern traits to help celebrate the momentous occasion. Arguably the most modern of these activities was the air show in the morning. The airplane was flown by pilot Art Smith (1890-1926), who flew an American plane on behalf of the event. Also added to the activities was the international Sri Lankan-style altar for bathing the baby Buddha, which also just so happened to be designed by Sri Lanka students studying in Japan at the time. Further activities included all participants wearing carnations in their coats, as well as military and children’s bands playing Buddhist music. And finally at the end of the festivities, the name of the emperor was called out three times. The first Hana Matsuri also had a distinct international flavor to it with Buddhist clergy from around the world including from India, Mongolia, and other Asian countries in attendance. This trans-sectarian festival drew the attention of the Japanese government, which allowed the Japanese to become more involved.

With the first Hana Matsuri being a resounding success, and with it being one of the largest public festivals in modern Tokyo, all Japanese Buddhist sects agreed that the festival should continue to be celebrated annually. In fact according to a newspaper at the time, they wrote “It [the festival] appears to encompass all Buddhist customs of the East.”

By 1919, colonial Taiwan (1895-1945) held its own Hana Matsuri in Taipei in a style similar to the one in Tokyo, which would be a harbinger of things to come for Korea; and Seoul in particular, by 1928.

Over time, Hana Matsuri would continue to grow in both size and scope in Japan. By 1924, the festivities and events associated with Hana Matsuri would require a larger venue. This venue would be Tokyo’s Hibiya Park. Also, the event would be centred on a long parade that began in Asakusa and ended in Hibiya Park. This parade included ornamental floats, dancing, and singing. Tens of thousands of people lined the parade route. Fireworks went off and flower petals were thrown along the parade path. In addition to the festivities, store owners also saw an up-tick in sales with shops and department stores offering various bargains and sales.

In 1925, the first airplane owned by Japan “scattered innumerable petals of colored paper lotus flowers.” By this point, Hana Matsuri became Tokyo’s signature festival. Soon afterwards, other major Japanese cities put on their own Hana Matsuri festival.

It was at this point that Japanese Buddhist took the initiative and decided to export Hana Matsuri to other Asian Buddhist countries, which happened at the second “East Asian Buddhist Conference in Tokyo” in November, 1925. In attendance were Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, and Western Buddhists delegates. The multi-national delegates created a manifesto for pan-Asian cooperation, which would attempt to create a “Buddha-ization of the world” to supplant Christianity as a religious unifier in the West. These delegates declared in writing, “At the day of the birthday of the great saint Śākyamuni [Seokgamoni-bul], all Buddhists shall hold the Buddha’s Birthday festival in unison and make it a custom of the world.” And with the resounding success of Hana Matsuri in Japan, the Japanese Buddhist delegates lobbied to have other Asian countries adopt their version of it. By doing this, Japanese Buddhists’ were attempting to counter the influence of the West and Christianity with an Eastern Buddhist international influence.

While most delegates of the conference were onboard in principle with the idea, they disagreed over the details like which date to hold the festival. While the Japanese now followed the Gregorian calendar, other nations like the Koreans and Chinese still followed the lunar calendar. So the Chinese Buddhist reformer Taixu (1890–1947) advocated for the traditional lunar date as followed by the Chinese and Korean Buddhists. Eventually, Taixu suggested the compromise of both dates being celebrated according to the customs of the given country. However, this would have major repercussions in Korea at a future date with the celebration of Hana Matsuri inside colonial Korea.

However, and with all this success, Japanese Buddhism was still beholden to the policies of their own government. Seeking to emulate Sri Lankan Buddhists’ success in being able to achieve a national holiday for Vesak, Japanese Buddhists also attempted to make April 8th a public holiday in Japan. And even with all this nationalistic momentum that Hana Matsuri and Japanese Buddhism had been garnering both religiously and for the nation, it still failed. However, this momentum points to the footing and confidence that Japanese Buddhist now felt they had to put forth such a proposal.

And while Japanese government rejected Japanese Buddhists call for a national holiday for Buddha’s Birthday, the governmental authorities recognized the importance of Buddhism and the role it would play in imperial Japan. With this in mind, Japan’s national and municipal governments fully embraced Hana Matsuri as a device and tool that would help further the image of Japan as the leader of the East politically, economically, and religiously.

1928 Buddha’s Birthday Festival in Seoul

Japan attempted to co-opt the growing popularity of the modern Buddha’s Birthday celebrations in Korea by introducing a re-interpretation of the festival for Korean consumption and enjoyment as seen through the lense of the colonizer on the colonized. In Japanese, this festival would be known as Hana Matsuri, which was known as Hwaje in Korean, or the Flower Festival in English, for this form of the Buddha’s Birthday Festival. This colonial government sponsored festival, the Hana Matsuri, which was a joint venture by Japanese and Korean Buddhist authorities, first started in 1928 and continued until the end of Japanese Colonial rule in 1945. Both Korean and Japanese Buddhists were attempting to manufacture a modern Buddhist festival in Korea that would help consolidate two people into one identity, while also combating aggressive Christian missionaries on the Korean Peninsula, as well. And it’s to the very first, the 1928 celebration, that we turn our attention to now.

The first ever Hana Matsuri Festival in Korea started on the morning of May 26th, 1928 (following the traditional Korean lunar calendar) at eight o’clock. The festivities began with five rounds of fireworks being shot from Mt. Namsan in Seoul. Two hours later, a celebratory airplane flew over the Seoul city population of some 300,000 souls. The airplane showered the city of Seoul with some one million blue and red petals and thirty thousand additional flyers promoting the ensuing festival.

In total, three different locations were selected in Seoul, which differed from the festivities in Tokyo that took place in one location at Hibiya Park. In addition to these three different locations, three different times of the day would divide the inaugural festival, as well. The first public event took place at the square in front of the Bank of Chosen at 11:00 a.m. with the Japanese Buddhist organization officiating it. At this first venue, fireworks and an airplane flight followed the event. By 1:00 p.m., the “Korean Buddhist Central Administrative Institution” took charge. The location of this early afternoon event took place in front of the Dong-a Ilbo (East Asia Daily) building. This was then followed by the last event of the very first Hana Matsui Festival at 3:00 p.m. in Jangchungdan Park, which was presided over by the “Association of the Celebration of Hana Matsuri.” There is no doubt that while the festival was religious, it was also political in nature, as well.

More specifically, the Korean Buddhist contribution to Hana Matsuri began with traditional rituals being performed at Gakhwangsa Temple (modern-day Jogyesa Temple) in the morning. The first Hana Matsuri festival was both a private and public celebration; and as such, as soon as the rituals were complete at Gakhwangsa Temple, the parade continued on away from the temple complex at Gakhwangsa Temple. A sculpture of a white elephant was led by thousands of both Korean and Japanese students, and they were all accompanied by Buddhists with lanterns and dozens of monks riding in five cars. Additionally, colourful flowers and floats were part of the procession. The procession then turned onto Jong-no Street, which drew a large turnout by the Korean population. As soon as the event was completed at the square in front of the Dong-a Ilbo (East Asia Daily) building, the procession continued on toward Jangchungdan Park, which was then joined by Japanese Buddhists and government officials. It was here that a state ceremony was conducted by the Japanese over the birth of the Buddha. This then completed the day’s official activities. In total, there were tens of thousands of people including children and some five hundred dignitaries, including the governor general and mayor of Seoul, who all participated in the inaugural celebrations. The municipal government of Seoul added buses and streetcars to help accommodate the influx of people to the city from the suburbs. As the Maeil Sinbo newspaper wrote on May 27th, 1928, about the inaugural festival “a rare spectacle, [not seen] in recent years” For the Japanese, as a whole, what this festival meant symbolically is the continued assimilation of Koreans into the Japanese Empire through Buddhism and Buddhist rituals.

What’s perhaps the most interesting aspect to the division of the Hana Matsuri festival into three parts, times, and places on May 26th, 1928, is that it highlighted the colonial separation that encompassed the city of Seoul at this time. In general terms, the central part of Seoul was divided into northern and southern halves with the northern half being largely occupied by the Korean population and the southern half being occupied by the Japanese population.

The reason for the location of these festivities is that the central office of Korean Buddhism was located in the northern half, while the temples of the Japanese Buddhist sects were located in the southern half of Seoul. Additionally, and economically, the Korean stores were congregated in Jongno, while the Japanese businesses were mainly congregated in the south on Main Street. So not only did the organizers have a symbolic meaning behind the festival, but they also had a strategic practical economic reason, as well. As for the third location, it seems to have been chosen as a symbolically significant location that was meant to reconcile the division found between the colonizer and the colonized.

And yet, despite the colonial government’s efforts to reconcile and assimilate the two people, economic disparities continued between the two communities. And this disparity would continue as colonial rule continued. In fact, numerous Korean stores in Jongno lost their businesses to Japanese entrepreneurs. In a way, organizers hoped that Hana Matsuri would help off-set some of the financial hardships that Korean businesses were suffering through. In fact, during the first Hana Matsuri, stores in Jongno lavishly decorated their windows and offered discounts to buyers. And as a result, and according to the Maeil Sinbo newspaper on May 26th, 1928, the day resulted in “very good” sales. Also, and rather obviously, it should be noted that by having one of the three locations being in the southern part of the city, the festival also benefited Japanese stores and businesses, as well. So it should come as no surprise that organizers deliberately planned to have the lantern parade route for Hana Matsuri pass through shopping areas like Jongno and Main Street in southern Seoul. Commercialism, just like it had been for the modern Korean Buddha’s Birthday celebrations before Hana Matsui, played a large part in the special day’s activities. Pleased with the success of the festival and their participation in it, the Korean Buddhist institution affirmed that it would continue to participate in the annual Hana Matsuri Festival. In fact, so successful was the 1928 Hana Matsuri that it spread from Seoul to other major Korean cities much as it had in Japan in years past.

By participating in the inaugural Hana Matsuri Festival in 1928, and continuing to do so until the fall of the Japanese in 1945, Korean Buddhists made the most of their situation. While previously oppressed and persecuted during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) for centuries with varying degrees of suppression, Korean Buddhists found a lifeline through the Japanese colonizers and the bond found between the two religiously. With Japan attempting to create a bond through pan-Asian Buddhism to combat western economic, cultural, and Christian religious influences, and with Korean Buddhists finally having a small chair at the table, Korean Buddhists made the most of events like the Hana Matsuri Festival and its popularity. Korean Buddhists did this through media coverage, which included radio, in hopes of attempting to reassert their relevance in Korean culture and society. Korean Buddhists filled public spaces through public discourse and engagement through the admissibility of Japanese colonial authorities. Once forbidden for centuries, it was now open a crack with a whole host of contingencies: but it was still open. Through their involvement with Japanese authorities, Korean Buddhists had prepared a modern festival for a modern Buddhism, when and if the time came, which it did in 1945. All of this groundwork was laid and continued to be laid through the very first Hana Matsuri Festival in 1928.

As a bit of an interesting aside, following Korean independence, Korean Buddhists continued to make the festival their own; so much so, that they further re-invented parts of its history. In 2008, the Jogye-jong Order, which is the largest Buddhist Order in Korea, published a book on the one hundred year history of the Lantern Festival entitled “A Century of the April Eighth Ceremony” to help provide a history to the “the identity of the Lantern Festival.” The only problem with this collection, which included news articles and pictures from the one hundred year history of the festival is that it excluded the entire colonial period. In this book, the editors posed the question, “Does the Lantern Festival of today have any connection to the Hana Matsuri of the colonial period?” In asking this, the editors definitively answered with a resounding no with the present-day form of the festival only dating back to 1955. Although the editors provide a longer history of the festival, including its pre-modern forms, the book does not mention the Hana Matsuri celebrations in colonial Korea and moves quickly into detailing the post-colonial version of the Lantern Festival.

Total War and Post-Colonial Buddha’s Birthday

Total War Buddha’s Birthday

By the late 1930s, Hana Matsuri in Korea was downsized. There are two distinct reasons for this. The first is that Japan had re-directed most of its resources and efforts towards their expansion into Manchuria, which would become the Second Sino-Japanese War (July, 1937 – Sept, 1945). And the second reason for the downsizing of Hana Matsuri at this time is that Japanese Buddhist faced an internal challenge. Japanese Buddhists in colonial Korea were becoming upset that they had to continue to follow the Korean lunar calendar for which date the Buddha’s Birthday was celebrated unlike in Japan which followed the Gregorian calendar.

Such irritation can be found in a Japanese Soto priest in 1933, when he states, “Do we really have to use the lunar calendar [for Hana Matsuri]? The country [the colonial government] is spending a huge amount of money. Next year, we should hold it according to the Gregorian calendar.”

So in 1937, and as a response to the Japanese Buddhists’ complaints, the colonial government attempted to further integrate Korea into Japan. As part of the national policy, which was first enacted in 1936, the colonial authorities decided that all Buddhists under their purview would follow the Gregorian calendar. So the 1937 celebration of Hana Matsuri on the lunar calendar would be its last. All subsequent festivals would follow the Japanese homeland that followed the Gregorian calendar. This would have a response that the Japanese didn’t expect.

What’s interesting about this change is that the Korean government had adopted the Gregorian calendar as early as 1895; however, this change failed to replace the old calendar. Instead, it seemed as both calendars co-existed. So the request didn’t seem outlandish, but it was yet another way that Koreans could passively resist their colonizer. Korean intellectuals had opposed such change, but this opinion didn’t gain any currency until the 1936 national policy changes enforced by Japan on colonial Korea. It was through this that the change was yet another vehicle for resistance.

What’s even more interesting, but not surprising, is that no Korean Buddhists were consulted about this change. Instead, it was Japanese Buddhists in cooperation with colonial authorities that unilaterally enacted this change. What would happen in practice is that while the thirty-one head temples in Korea and the central office of Korean Buddhism in Seoul, which fell under the direct jurisdiction of the colonial government, followed the new April 8th Gregorian calendar change, the colonial government didn’t fully enforce this change. This could most noticeably be seen in rural parts of the country that still continued to follow the lunar calendar. In fact, there was very little that Japanese authorities could do. This would reflect the resistance that was occurring at the grassroots of Korean Buddhism. This type of resistance, just like the head temples forced participation, would continue until the end of the war.

An even greater problem for the Japanese, outside the lack of rural participation in Korea, is that as a whole a vast number of Koreans lost enthusiasm for the Hana Matsuri festival. While the reason might seem inconsequential today, most Koreans at this time viewed the lunar calendar as part of their cultural and national identity. So when this aspect of the Hana Matsuri was stripped away, Koreans believed that part of their cultural identity and linkage to the festival had been stripped away, which only further alienated Koreans.

As Yun Chiho (1864-1945), who was an important political activist and thinker during the late 1800s and early 1900s in Joseon Korea, wrote in his diary in January, 1930, “The Korean population has come to ignore the fact that the Gregorian calendar is the calendar of the country. The people almost unconsciously do this as a form of silent protest against Japanese domination.”

In addition to the disagreement over the lunar versus Gregorian calendar, there was also disagreement over finances for the festival, as well. The colonial city government of Seoul had been giving 2,500 yen (or 1,647,500 yen today, which is about 12,100 USD) annually to businesses directly involved with Hana Matsuri. This amount would later be increased to 7,000 yen (or 4,613,000 yen today, which is about 33,864,000 USD). But the problem with this was the prioritization of the funds which exclusively went to the “Association of Japanese Businesses.” As a result, the “Association of Korean Businesses” complained that not a “single yen [was given] to the Korean Association.”

Despite these difficulties and ensuing problems, the 1937 Hana Matsuri, the last of which followed the lunar calendar of the April 8th date, was largely successful. All the locations of the Hana Matsuri had high attendance. The reason that the festival continued to be so successful throughout the country is that the festival continued to be a distinctly Buddhist festival in Korea at a time when so much of Korean culture was being suppressed.

However, with Japan being fully immersed in World War 2 by 1941, the colonial powers in Korea changed the format and structure of the Hana Matsuri festival. One change was deciding to have the festival at one location instead of three with the hope for greater unity. And by 1943, with Japan now having limited resources because of a losing war, the Hana Matsuri festival was scaled back. The festival was far more regimented and held indoors.

Post-Colonial Buddha’s Birthday

As soon a Korea gained independence from Japan in 1945, Korean Buddhists and Buddhism quickly annulled the Japanese colonial government’s rules and regulations. In turn, Korean Buddhists created their own infrastructure and by-laws. One such major bone of contention between Korean Buddhists and Japanese Buddhist was the lunar date to celebrate Buddha’s Birthday. Korean Buddhist’s reverted to the lunar calendar date to celebrate Buddha’s Birthday starting in 1945. Another change was that Korean Buddhists stopped calling the festival Hana Matsuri; instead, they replaced the celebration with the name the Lantern Festival, or “Yeonggotchukjae – 연꽃축제” in Korean.

Other than these few changes, the format and structure of Hana Matsuri carried over to the Korean Lantern Festival. An organized procession, both pre and post-parade events, carnations, floats, and Japanese-style lanterns continued to be at the very heart of the newly interpreted celebration of the Lantern Festival. As such, the Hana Matsuri of colonial Korea played an integral role in the modernization of Buddhism.

In addition to the continuation of the overall structure of the celebrations, Korean Buddhists also continued to use the same phraseology of other Asian Buddhists that was used since the 19th century. Ideas of making Korean Buddhist more international, popular and more socially acceptable in Korea were all new hallmarks to the re-branding of Korean Buddhism. With this in mind, post-colonial Korean Buddhism continued to present the Lantern Festival, and Buddhism as a whole, as a broad-based and national event; that at its very core, was the embodiment of Korea’s national cultural heritage and identity.

Currently in Korea, municipal governments work in partnership with Buddhists and Buddhist organizations to present the Lantern Festival in combined cultural, national, and modern terms. Generous financial support is provided, as the festival is recognized as an official cultural event. While state involvement in the festival is less noticeable than colonial years, Korean authorities are still quite involved in the festival to maximize the national sense of pride that the Lantern Festival embodies.

Rather interestingly, Korean Buddhism took a backseat to the growth of Korean Christianity in post-colonial Korea when U.S. occupation forces took control of administrating part of the peninsula. The government shifted from a pro-Buddhist to pro-Christian stance for obvious reasons. One indication of this shift was that the U.S. military government designated Christmas as a national holiday in 1945, which was continued and adopted by the subsequent pro-American Korean governments. It wouldn’t be until 1975, after decades of legal wrangling, that the Korean government finally decided to declare the Buddha’s Birthday a national holiday.

In Japan, on the other hand, Hana Matsuri suffered a different fate. Despite Japanese Buddhists attempts from the late 1920s to make Buddha’s Birthday a national holiday, it would never happen (and still hasn’t happened). Once so powerful in attempting to disseminate and promulgate the modern Japanese version and brand of Buddhism, Hana Matsuri is now only a ceremony confined and conducted at individual Japanese temples. Instead of being national in Japanese, it’s localized. There are arguably many reasons for such a decline; but perhaps the best is that pre-war Japanese Buddhism was infused with the rise of Japanese nationalism as both a colonial and imperial power. In this way, Japanese Buddhism, at least during the colonial period, can be viewed as an institution that adapted itself to a new social situation in which they could gain political influence and power.

Conclusion

Facing the very real situation of increased marginalization and perhaps eventual demise, Korean Buddhism pivoted through the auspices of Japanese governmental rule on the Korean Peninsula during Japanese Colonial Rule. Already facing the need to modernize so as to stay relevant in a rapidly changing country, Korean Buddhism looked for ways that they could succeed. And one of these avenues was through the re-interpretation and modernization of Buddha’s Birthday, which was the most important festival and celebration of the Korean Buddhist calendar year. While already on their way towards modernizing, Korean Buddhism was co-opted by Japanese Buddhism to further their own goals in the very real opportunities of a shifting governmental power struggle in colonial Korea. Japanese Buddhism hoped to gain favour both at home and in Korea with authorities by placating to their needs. As such, Japanese Buddhism was weaponized in a form of Japanese Buddhist nationalism to fill the ongoing needs of their government. And while Japanese Buddhism was doing this, Korean Buddhism used these newly opened opportunities in Korean society, through the acceptance of both the waning Joseon government and the newly formed colonial government, to create opportunistic avenues of their own. Using Japanese Buddhism as a vehicle, and Hana Matsuri as a tool, Korean Buddhism attempted to further modernize and gain favour with the Korean population as a whole. And when Japan lost the war, Korean Buddhism continued to use what they had learned during Japanese Colonial Rule to further their own goals which helped take root in colonial Hana Matsuri and future post-colonial Lantern Festivals. As such, Hana Matsuri wasn’t so much an imposition of the colonizer on the colonized, but it was more of a dynamic feature used by Korean Buddhists to help modernize Korean Buddhism in a Japanese colonial context.