Excess, Invasion and the Tripitaka – The Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392)

Early Goryeo – 918-1000

At the end of the Unified Silla Dynasty (668-935 A.D.), there was a lot of political turmoil and chaos. As a result of this political instability, the Silla Dynasty was highly weakened and vulnerable. Specifically, the loss of control over local lords at the end of the 9th century led the nation into civil war. Under the rebellious leadership of Gung Ye (869 – 918 A.D.) and Gyeon Hwon (867 – 936 A.D.), they formed two independent states. Gyeon Hwon formed Hubaekje (meaning Later Baekje), while Gung Ye established Hugoguryeo (meaning Later Goguryeo). It was under these tumultuous conditions that Wang Geon, a subject of Gung Ye, overthrew his Hugoguryeo leader. In doing this, Wang Geon established the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) in the former Baekje and Goguryeo territories in 918 A.D.. With this, Wang Geon ascended the Goryeo throne and became known as King Taejo of Goryeo (r. 918-943 A.D.). In 935 A.D., King Gyeongsun of Silla, who reigned from 927-935 A.D., surrendered to King Taejo of Goryeo. Then, in 936 A.D., King Taejo of Goryeo destroyed the last rebellious vestiges of Hubaekje. With this, Goryeo reigned over an entirely unified Korean peninsula.

As a devout Buddhist, King Taejo of Goryeo continued to promote Buddhism. Not only this, but Buddhism continued to prosper as the national religion. King Taejo of Goryeo believed that the formation of the Goryeo nation was made possible because of Buddhist laws and teachings. As a result, King Taejo of Goryeo fully encouraged the construction of temples and pagodas throughout the Korean peninsula, especially around the Goryeo capital of Kaeseong. However, not only was Korean Buddhism believed to be a nation builder, but it was also believed to be a state-protector and a guide in how to rule over the Goryeo nation. Specifically, these guiding principles can be observed in the Mahayana sutra of “Inwang Hoguk Banya Gyeong,” or “The Humane King Sutra” in English, when it states, “If the people are threatened by disasters such as invasion, disease, drought, or flood, the king should keep and read this sutra and open practicing places to make offerings, praising the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and holy statues. If this is done, then Buddhas and Bodhisattvas will protect the nation, the king, and the people forever.” The state protecting nature and ruling ideology brought forth by Korean Buddhism was especially important at this time in Korean history because of repeated foreign invasion by the likes of the Khitan and Mongols all across the Korean peninsula. And it was King Taejo of Goryeo’s belief that Buddhism would help solidify the nation’s security and prosperity. This is further emphasized by the “Ten Rules” or “Hunyo-sipjo” in Korean, that the Goryeo government used to govern the nation. In the very first rule, it states, “The great task of a nation should be based on the help of Buddha. Therefore, build monasteries and let masters carry out their work.” Not only was Buddhism the state religion, but it was an integral part of the entire Goryeo nation.

Religiously, King Taejo of Goryeo allowed for the development of both Seon (meditation) and Gyo (doctrinal) sects equally. This allowed for the balanced growth of Korean Buddhist belief. And because King Taejo of Goryeo respected and believed in Buddhism, he allowed for Indian monks to visit Goryeo. This allowed for the exchange of Buddhist beliefs and culture.

The tradition that King Taejo of Goryeo established early in Goryeo rule was the establishment of Buddhist institutions like temples and hermitages. This tradition was passed on to future kings. All Goryeo kings were devout Buddhists, so they also engaged in building temples, offering food to monks, and performing various Buddhist rituals. So revered were Buddhist monks in Goryeo society, that they occupied privileged positions in court. It was King Gwangjong of Goryeo (r. 949-975 A.D.) that really promoted Buddhist services both to early Goryeo kings, as well as to his subjects. Buddhist services at this time were becoming excessive, so King Seongjong of Goryeo (r. 981-997 A.D.) ordered restrictions to be placed on these Buddhist ritual services. However, these restrictions were but a fleeting moment as King Mokjong of Goryeo (r. 997-1009) quickly reversed the restrictions on Buddhist ritual services and allowed for the excesses of these services to return, once more.

Of note, it was just prior to Goryeo rule that one of Korean Buddhism’s greatest innovation was popularized. The monk Doseon-guksa (827-898 A.D.) practiced geomancy, or “Pungsu-jiri” in Korean. Pungsu-jiri interprets the topography of the land, which then determines the fate of future events and the strength of a nation. As a result, temples and hermitages were built on land that was thought to be auspicious. Once more, the state of the Goryeo nation, good or bad, was closely linked to Buddhism, and this would be one of the most influential teachings guiding the future of Goryeo Buddhism.

Mid Goryeo – 1000-1199

Great excess and historic feats were completed during the middle period of the Goryeo Dynasty from 1000 to 1199. During the reign of King Hyeonjong of Goryeo (r. 1009-1031), the Lotus Lantern Ceremony was revived, and a number of Buddhist temples were continually being built. At this time, there was a continued belief that personal and national well-being was assured through pious acts as interpreted by Buddhist teachings. This deep respect that Goryeo had for Buddhism led to the establishment of exams for monks, which were based on the state civil service exam. King Jeongjong of Goryeo (r. 1034-1046) allowed for every one in four sons to become a monk, which was an increase from the previous one in five sons. As a result, many royal princes became monks, with the addition of aristocrats, as well. This helped increase the number of monks throughout the nation.

With the stability of the nation slowly taking shape, the ritualization of Goryeo Buddhism reached its peak. Once more, the household monk policy was lowered. Now, one in three sons could become a Buddhist monk. It is also at this time that monks received land allotments from the Goryeo government. Monks were also exempt from compulsory national labour duties, which also helped raise the national monk population. Temples also continued to increase their land through royal and aristocratic donations, commendation by peasants, and outright seizure of land. And because Buddhist land enjoyed tax exemption, Buddhism, as an organized religion, grew more and more powerful economically. They further increased their wealth by setting up Buddhist endowments, relief granaries, wine-making facilities, and the raising of livestock. And to protect all of their financial and material interests, temples trained their monks as soldiers.

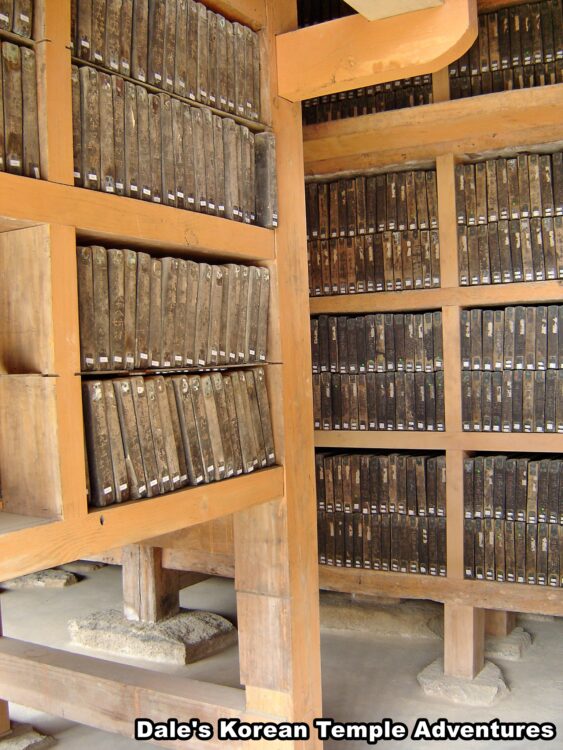

It was at this time of Buddhism excesses that several monks rose up to combat the excessiveness of wealth and ritualization found in Buddhism. For them, this excessiveness created an unhealthy and hostile environment that stunted the development of personal and collective Buddhist thought. One such monk was Uicheon (1055-1101). Uicheon was the fourth son of King Munjong of Joseon (r. 1046-1083). Uicheon collected about four thousand volumes of Buddhist texts while studying in China. It is from these texts, when he returned to the Korean peninsula, that the first set of the Tripitaka Koreana were completed in 1087. This set was comprised of the Buddhist scriptural canon in Chinese translation. Tragically, this first edition was destroyed by fire by the invading Mongol army in 1232. But in 1251, a mere nineteen years after the first set had been destroyed, was a second set of the Tripitaka Koreana completed. The white birch used to create the 81,258 blocks that comprise the Buddhist scriptural canon came from Wan-do Island in Jeollanam-do, and Geoje-do in Gyeongsangnam-do. The head office for the carving of these blocks was at Seonwonsa Temple in Ganghwa-do Island, and the branch office was in the Namhae area of Gyeongsangnam-do. Presently, the second edition of the Tripitaka Koreana is housed at Haeinsa Temple near Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do. The Haeinsa Temple Tripitaka Koreana collection is the oldest and most accurate in the world.

In addition to this remarkable contribution to Korean, and worldwide, Buddhism, Uicheon also attempted to reconcile the national Buddhist sect divide in Goryeo. Because King Taejo allowed for both Seon (meditative) and Gyo (doctrinal) sects to develop together, they also developed an antagonism against the other. In an attempt to reconcile these differences, Uicheon mixed elements of Seon with Gyo and added in a little of the Avatamsaka teachings to produce the new Buddhist sect called Cheontae Buddhism. And while it became a force in its own right, it did little to ease the tension between the different Buddhist sects.

During the reign of King Uijong of Goryeo (r. 1146-1170), Buddhist services revolved around praying for good fortune. It is also at this time that monks started to take advantage of the royal court, and King Uijong of Goryeo in particular. Temples were now directly competing with each other to gain considerable financial favour from the royal court and aristocrats. As a result, a lot of unspeakable damage occurred both materially and socially at this time.

During the early reign of King Myeongjong of Goryeo (r. 1170-1197), there was a military rebellion headed by the Lee brothers: Junui and Uibang. They both supported the young king; however, they were drawn into the internal politics of the time. Because the national religion was Buddhism, the military wanted its support. But because Buddhism was divided into two powerful sects, the Seon and Gyo, the two sects supported the military differently. While Seon supported the military, Gyo did not. Once again, the tension between the two Buddhist sects grew. And this divide wouldn’t be reconciled for years to come.

Interestingly, it is also under King Myeongjong of Goryeo’s reign, during the fifth year of his rule, that the excesses of Buddhism were curtailed once more. This time, the king prohibited drinking and luxurious items from temples like gold and silver Buddha and Bodhisattva statues. But like his royal predecessors, King Myeongjong of Goryeo would also fail to completely curtail the excesses of Buddhism as the years to come would prove.

Late Goryeo – 1200-1392

The excesses of early to mid Buddhism during the Goryeo years would result in some wide ranging changes to the national religion both socially and economically. But those changes were still on the horizon in 1200. For the time being, excessive Buddhist ceremonies, economic power, and monk privilege still reigned in the early part of the latter stages of Goryeo rule.

With nearly thirty years of resistance, the Goryeo government, under King Gojong of Goryeo (r. 1213-1259) fell; in its place stood a Goryeo government controlled by the Mongols. It is at this time that the belief in Buddhism as a national protector weakened. Gradually, the mood to expel the excessive nature of Korean Buddhism began to grow.

During this time, there started to occur a growing acceptance of Confucianism, which brought a rational approach to the problems of human affairs. However, at this time, Confucianism didn’t reject Buddhism. It wasn’t until the later Neo-Confucianists that this rejection occurred. Instead, at this point in history, Buddhism dealt with the salvation of the immortal soul, while Confucianism focused on earthly affairs. As a result, a lot of men were well versed in both Confucianism and Buddhism.

With a growing dissatisfaction in both Confucianism and Buddhism by the new literati, Neo-Confucian doctrine started to replace both. Neo-Confucianism is a philosophical doctrine based on Confucianism, which explains the origins of humans and the universe in a metaphorical way. And with this turn came the increasing rejection of Korean Buddhism. At first, the rejection of Buddhism by the Neo-Confucians was mainly aimed at the excessive nature of Buddhist services. And the way that Neo-Confucians went about attacking Buddhism was to attack these excessive abuses, rather than attacking the Buddhist belief system. These excessive abuses, other than Buddhist services, were the wealth and power of temples, as well as the misconduct of monks.

However, at this very same time, there were still positive elements of the Buddhist faith occurring in Goryeo. One positive aspect is that some of Korea’s oldest history books appear at this time, like “Lives of Eminent Korean Monks,” or “Haedong Goseung Cheon” in Korean, which was written in 1215. Also, the Samguk Yusa, or “Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms” in English, was written at this time by the Buddhist monk Iryeon (1206-1289).

In addition to these writings, foreign Buddhist monks came to visit Goryeo. Many monks from Yuan China came, and vice versa. And in 1276, monks from Tibet arrived in Goryeo. They were called the “Teachers of the King,” as King Chungnyeol of Goryeo (r. 1274-1308) specifically asked for them to pray for the health and good fortune of his daughter, the princess. Unfortunately, and further damaging the image and reputation of Buddhism during this time, these Tibetan monks ate meat and drank alcohol. Already having a negatively viewed image in the eyes of public opinion, these Tibetan Buddhist monks certainly didn’t help the situation.

The positive attitude towards Korean Buddhism really started to change in the royal court during King Chungseon of Goryeo’s reign from 1308-1313. He made a new law that stated, “It’s a law that if one becomes a monk, then one should bow neither to a king above nor to the parents below. As such, do not appoint a monk to an official post regardless of his greatness.” This law attempted to curb Buddhism’s power in Goryeo. This was furthered by a comment made by Lee Saek, a public official, when he stated, “Monks did damage to civilians through laziness and idle life, and it shakes the nation’s power.” Already, the tides of change had started to affect Korean Buddhism. Its negative image was about to enter the Dark Ages of the Joseon Dynasty years.

In the final few years of Goryeo rule, King Gongmin of Goryeo (1351-1374) prohibited people from randomly becoming monks in 1361. And during King Gongyang of Goryeo’s reign, 1389-1392, women were no longer allowed to visit temples. The argument that opponents of Buddhism had in the waning years of Goryeo were against Buddhist doctrine. Neo-Confucians now believed that Buddhist doctrine to be worthless and vain. It was with this attitude towards Buddhism that Goryeo Dynasty ended, and the Joseon Dynasty began.