Gamno-do – The Sweet Dew Mural: 감로도

Introduction

One of the more difficult Buddhist murals to find at a Korean temple is the Gamno-do, or “Sweet Dew Mural” in English. In fact, I’ve only ever seen this mural at a handful of temples and hermitages in all of my travels. So what is a Gamno-do? What does it look like? And what is it supposed to mean?

The Buddhist Afterlife

Before we can better understand the Gamno-do, we must first better understand the Buddhist afterlife, for the afterlife is central to better understanding the symbolism found in the Sweet Dew Mural.

In Buddhism, death doesn’t mean the end; instead, death is but a part in the process of reaching another life. So in Buddhism, death is an illusion. With this being the case, almost all sentient beings, outside of those that have attained Nirvana, progress either through life in this world or in the underworld. And while people pass through the underworld, they reflect upon the actions they have committed since their beginning. Afterward, sentient beings are reborn into the Six Paths, which are heavenly beings, humans, asura, animals, hungry ghosts, and residence of hell. And until a sentient being achieves Nirvana, they go through this cyclical process of reincarnation through the Six Paths.

During this process of transmigration between the Six Paths, there are four stages of existence. They are “basic existence” in this world or “bonuyu” in Korean; “death existence,” or “sayu” in Korean; an “intermediate existence” between death and rebirth, which is known as “jungyu” in Korean; and “rebirth existence,” which is known as “saengyu” in Korean.

The Gamno-do, or “Sweet Dew Mural” depicts the “intermediate existence” found between death and rebirth. And the imagery captured in this mural depicts this journey. Even though Buddhism was severely suppressed during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), for a Confucian-first policy, Buddhism was still able to develop the formal rituals required for those that had died. This was especially true during the 16th and 17th centuries. This was in large part because of the wars and natural disasters that took place on the Korean Peninsula during this time. Because of this social unrest, the Buddhist community was able to help console the living through these difficult times through funerary rituals that helped calm the souls of the dead; and hopefully, lead the dead onto paradise through such rituals as the Water-Land Ritual.

The Water-Land Ritual

So what is the Water-Land Ritual that’s so central to the Buddhist belief system? The Water-Land Ritual is conducted to liberate the creatures of both water and land. In Korean, this ritual is known as the “Suryukjae.”

There are several ritual manuals that outline the Water-Land Ritual. Most manuals begin by explaining the motives for performing the Water-Land Ritual and the origins of the ritual. The ritual then proceeds from building the altar and purifying the surroundings to summoning messengers to open the way for the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to arrive that will assist the wandering souls. First, the low-ranking wandering souls are called followed by higher-ranking wandering souls; until eventually, the Bodhisattvas and Buddhas are invited.

Because it can be difficult for monks or nuns to call upon the wandering souls of the dead, it can take a considerable amount of time and effort to call them forth. According to the ritual manual for the Water-Land Ritual, while monks and nuns ring a Vajra bell, they repeatedly call out to the souls until late into the evening. Typically, monks and nuns will chant, “As the night sky darkens and grows serene, galactic waves sink into the mind.” While this is being said, incense and Buddhist hymns are recited, as well.

To help highlight the efforts of the monks and the nuns that conduct the Water-Land Ritual, they typically appear in the Gamno-do, as well. Traditionally a monk or nun stands apart from a group of other monks in the painting. This monk or nun holds a small bowl in their left hand in front of the altar, while raising their right arm above their shoulder. The monk or nun makes a gesture with their right hand. This hand gesture indicates the Water Wheel mudra, which symbolizes the action of bestowing sweet dew over the multitude of wandering souls, including agwi (hungry ghosts), who have been summoned to the ceremony.

And the reason that this is all done is that the Water Land Ritual is mainly conducted to placate the wandering souls of those that have died. This is especially true for those individuals that don’t have ancestors or descendants to hold a memorial service for them. As a result, these wandering souls are unable to pass through into the afterlife because they are in a state of an “intermediate existence” between death and rebirth, which is known as “”ungyu” in Korean. These souls are represented as hungry ghosts, which are known as “agwi” in Korean, or “preta” in Sanskrit. Also, those in a state of “jungyu” are known as “jungeumsin,” which means “lonely wandering souls” in Korean, or more commonly as ghosts. So it’s to this idea that the Gamno-do depicts the Water-Land Ritual and the journey of the soul through iconographic motifs. The Gamno-do was developed during the 16th and 17th century, as well. This all-new Buddhist iconographic form of art was produced nationwide with the norms of the Water-Land Ritual in mind. But how was this done?

The Gamno-do Design and Its Symbolism

A Gamno-do depicts the Ullambana sutra. Other names for this type of painting is “Gamnowang-do” or “Gamno-taenghwa.” The goal of the painting is to feed the agwi (hungry ghost), while also lessening the pain of those that are already suffering in the afterlife. The actual word, “Gamno-do” is a reference to the delicious food, food that tastes as sweet as nectar after a long drought, that’s being offered.

More specifically, the “agwi,” or hungry ghosts, are depicted in various ways which help highlight the concepts of loathing, hunger, thirst, avarice, pain, and fear. This is a central motif in the imagery of the Gamno-do. This only helps to further emphasize the negative idea that these souls have while journeying through as lonely souls, as they attempt to make their way towards salvation, rebirth, and paradise. This is done by juxtaposing simultaneously the harsh iconography of the agwi with the redemptive iconography of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

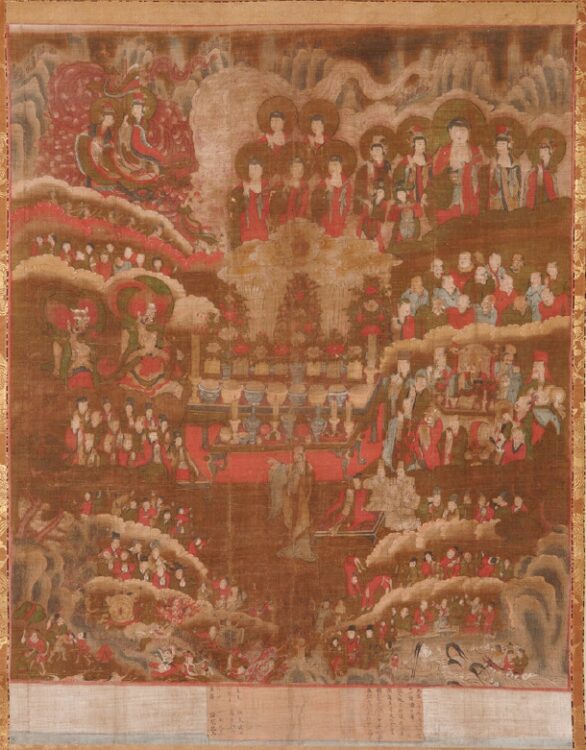

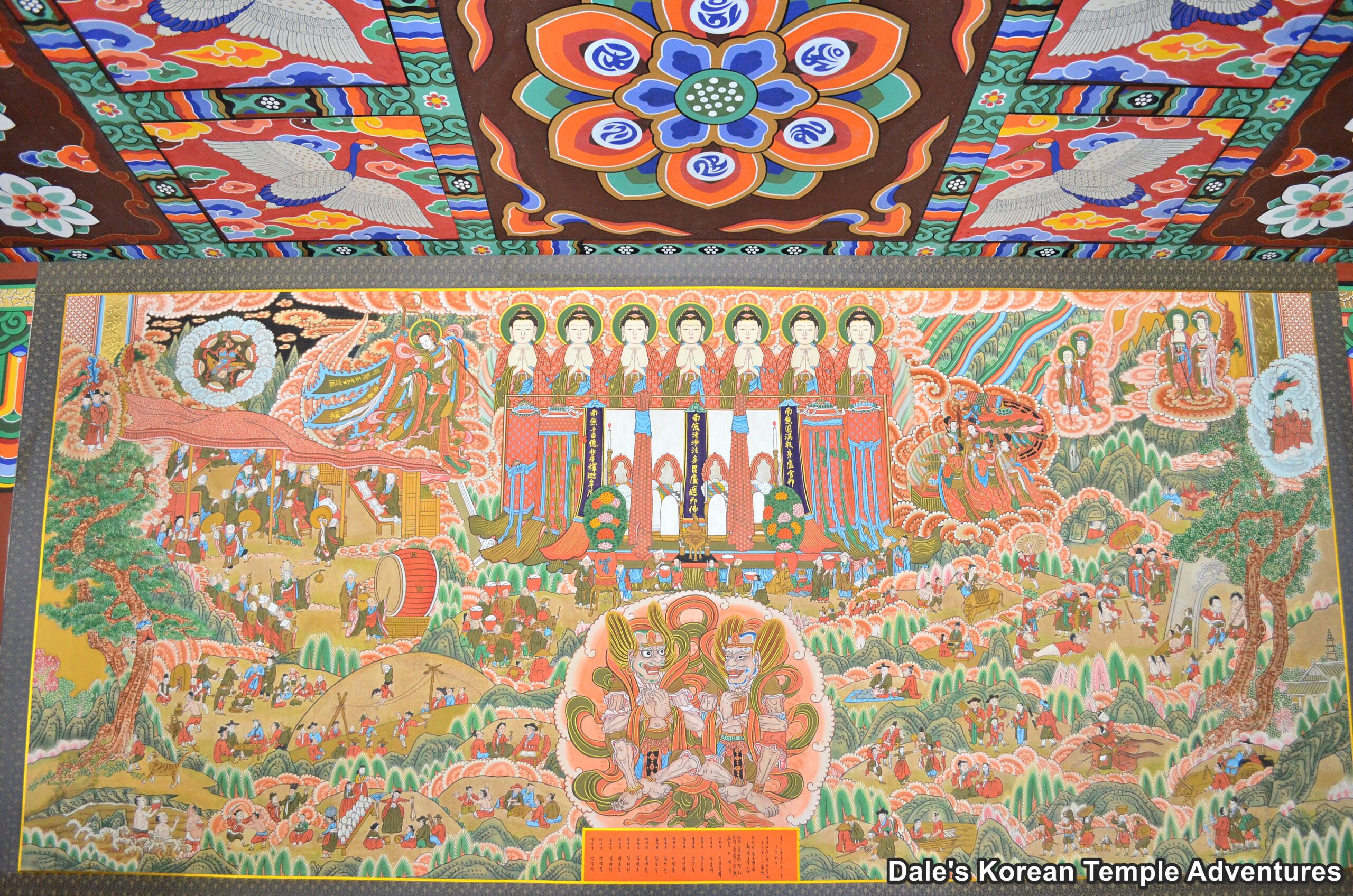

So more specifically, how is this done on the surface of a Gamno-do (Sweet Dew Mural)? Traditionally, a Gamno-do is divided into three sections: upper, middle, and lower sections. What’s important about this division is that all three sections depict different stages in the Water-Land Ritual; and therefore, are interconnected. In the upper portion of the Gamno-do, you’ll find an assortment of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that are related to salvation. Typically, there are seven Buddhas, as well as a Soul Guiding Bodhisattva, which indicates a future for the wandering souls. The lower section, on the other hand, portrays those beings that need to be saved. And the middle section with the altar and ritual scene, they symbolize the present moment that connects the past (the lower section) with the future (the upper section). Put in another way, the three sections represent the temporal progression of the ritual in pictorial space. So visually, the Gamno-do progresses from the middle section, to the lower section, and then upwards towards the upper section.

The Upper Section of the Gamno-do

Visually, the upper section of a Gamno-do consists of a centralized image of Amita-bul (The Buddha of the Western Paradise). Amita-bul is welcoming sentient beings into the Pure Land alongside six other Buddhas (for a total of seven). The Bodhisattva in the mural that stands to the side with a flagpole in their hand is leading the dead towards the Pure Land, as Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion) and/or Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife) descend from the clouds.

The Seven Buddhas that include Amita-bul appear to be descending down towards the ritual scene to bestow their “sweet dew.” This sweet dew is given to help save hungry ghosts. These hungry ghosts, in turn, absorb the sweet dew throughout their entire body; and from this process, they are released from their pain. This, in essence, is the main goal of the Gamno-do. After they have received this sweet dew and been relieved of their suffering, the agwi then head towards paradise in the upper section of the painting. They are guided by Seven Buddhas and reborn.

In total, there are Seven Buddhas that appear in the upper section of the Gamno-do. For the most part, artistically, they are indistinguishable from one another. These Buddhas are:

1. Dabo-bul – Prabhutaratna Tathagata: The Buddha of Abundant Treasures, who helps lonely souls abandon greed and stinginess and become fully equipped with the dharma.

2. Boseung-yeorae – Ratnaketu Tathagata: The Buddha of Treasure and Victory, who leads lonely souls to abandon evil and achieve the peace they seek.

3. Myosaeksin-yeorae – Surupakaya Tathagata: Known as the Buddha of the Fine Form Body, this Buddha cleans the repulsive forms of the lonely souls.

4. Gwangbaksin-yeorae – Vipulakaya Tathagata: The Buddha of Broad Extensive Body allows lonely souls to be freed from their bodily forms on their journey towards the Six Paths and obtain new bodies.

5. Ipowoe-yeorae – Abhayamkara Tathagata: The Buddha of Leaving Fear helps lonely souls to leave behind fear and gain Nirvana.

6. Gamnowang-yeorae – Amrtaraja Tathagata: As the Buddha of the Nectar-King, this deity opens the throats of all lonely souls, which are as thin as needles, to enable them to taste the sweet dew.

7. Amita-bul – Amitabha Tathagata: Called the Buddha of Infinite Light, or the Buddha of the Western Paradise, this deity causes lonely souls to transcend life and be reborn in the Western Paradise.

Each of the Seven Buddhas have unique supernatural powers. During the Water-Land Ritual, the monk conducting the ceremony invokes the name of all seven Buddhas in order: 1. Dabo-bul, 2. Boseung-yeorae, 3. Myosaeksin-yeorae, 4. Gwangbaksin-yeorae, 5. Ipowoe-yeorae, 6. Gamnowang-yeorae, and 7. Amita-bul. As each of the seven Buddhas appear in order, they erase the suffering of the lonely souls. And because all seven are called in order, they are presented in the Gamno-do together in the upper section of the mural.

More specifically, Dabo-bul attempts to erase worldly desires, which is the ultimate cause of being reborn as an agwi (hungry ghost). The second Buddha, Boseung-yeorae, he frees agwi (hungry ghosts) from the pain of their evil ways that stems from their misdeeds in their former life. In general, these first two Buddhas release individuals from their karmic bonds of being reborn as hungry ghosts.

Meanwhile, the third and fourth Buddhas, Myosaeksin-yeorae and Gwangbaksin-yeorae, focus on healing the appearance of the hungry ghosts. They are then followed by Ipowoe-yeorae, who removes fear experienced by the agwi (hungry ghosts), who have lived in their current form for an extended period of time. The sixth Buddha of the Gamno-do is Gamnowang-yeorae, who opens the hungry ghosts’ throats, which are as thin as a needle. This allows the agwi to taste the nectar of the sweet dew; and in turn, it liberates them from their hunger and thirst that is constantly tormenting them.

After being fed the nectar, the agwi are no longer hungry ghosts, so the seventh Buddha, Amita-bul, can help these souls transcend the cycle of rebirth along the Six Paths and be reborn in the Western Paradise. And the Soul-Guiding Boddhisattva that typically appears on one side of the upper section of the Gamno-do (Sweet Dew Mural) directs these souls to paradise after they have escaped being an agwi (hungry ghost) thanks to the nectar of the sweet dew.

The Middle Section of the Gamno-do

Visually, and in the middle section of the Gamno-do, you’ll traditionally find one or two agwi (hungry ghosts) with a bulging belly, constricted throat, and pin-hole mouth. They are typically fighting over food in front of an ancestral rites table. And on either side of the agwi, you’ll find monks performing the ceremony for the dead by chanting, ringing a hand bell, cymbals, or striking the Dharma Drum to help comfort the souls of the dead.

Symbolically, the middle section of the Gamno-do represents a scene of Buddhist monks conducting a ritual in front of an altar. The altar is adorned with various dishes that are required of the ritual. Included alongside the dishes are lamps and banners. This scene embodies the hopes and wishes for salvation of those souls being prayed to during this ritual. And the ritual is conducted on the behest of devotees who are attempting to accumulate merit and move the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to confer grace upon the agwi; which, in turn, will save them by breaking the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

More pressingly, the central idea found in the Gamno-do is the idea of salvation found in the essence of the hungry ghosts. It’s through them that we discover the centrality of the Water-Land Ritual and the redemption found in appeasing the wandering souls of the dead. It’s through this ultimate realization that paradise can be achieved by these wayward spirits that we realize that we are agents of change. And it’s this redemption and salvation that resides both in the Water-Land Ritual and that’s captured in the Gamno-do.

The Lower Section of the Gamno-do

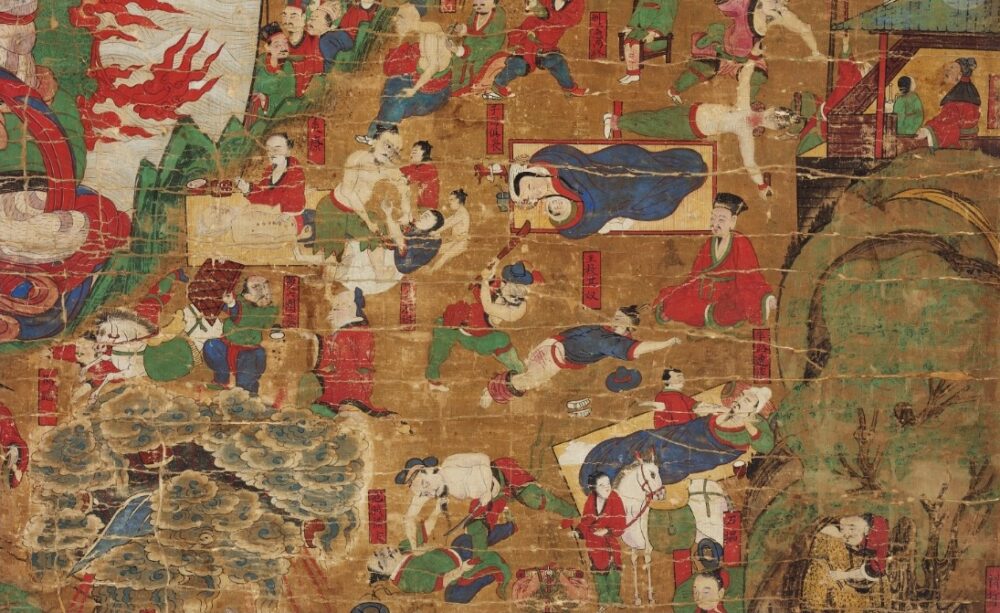

Visually, and in the lower section of the Gamno-do, you’ll find the realistic portrayal of the Six Realms of existence, which are hell, agwi, animals, humans, asura (large demons), and heavenly beings. Hell, agwi (hungry ghosts), animals, and asura, are portrayed as though they were alive in the present day. And each artwork varies depending on the mural’s artist.

Symbolically, the lower section depicts the wandering, lonely soul’s appearance in their former life. The lower section depicts a world where all sentient beings, including agwi (hungry spirits), are trapped in endless transmigration along the Sixth Paths. The past lives of the lonely souls, as depicted in the lower section of the Gamno-do, are similar to our present lives. The point is to reflect this reality back onto us. Over time, this lower section has become rather standardized typically portraying life during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).

More generally, the lower section of the Gamno-do consists of about forty scenes. In the upper portion of the lower section, and closer to the middle section’s altar, you’ll usually find the forlorn images of wandering souls like officials, generals, and soldiers who sacrificed their own lives for the sake of their countries. Other images that appear in this area include late kings and queens who favoured Buddhism and performed good deeds in their lifetimes. This area also includes the images from the Buddhist community like monks, nuns, and lay-people.

Typically, social standing is displayed in the Gamno-do. The bottom portion of the lower section includes those wandering souls of lower social status like a troupe performing out in front of a temple, wanderers who have starved to death away from home, and those that have died alone after growing old. Also included in this group are those that have died after being bitten by animals, trampled underfoot by horses, drowned, crushed to death by a collapsing house, or even consumed by wildfire. The main motif here are the causes of tragic death by the wandering souls while they were humans. There are deathbed scenes where people die while away in a foreign land. These motifs represent loneliness and regret on the part of the wandering souls. The unforeseeable is what they represent most clearly in this lower section of the Gamno-do.

The Importance of Hungry Ghosts in Gamno-do

Despite the fact that Joseon people couldn’t see ghosts or spirits (and we still can’t), they believed strongly in them. They believed in a countless number of spirits that included those that had deep seeded regrets; and in turn, were thought to interfere with human lives. In Korean, these spirits are known as “gohon.” An especially bitter spirit is known as “mujugohon.” These are spirits that have died while they were away from home. They died unexpectedly in a disaster or accident. The reason for such bitterness is that they were unable to receive memorial rites. And nationally, during the 16th century, over a 150 year period, there were severe climate changes that resulted in bad harvests. This, in turn, resulted in famines, epidemics, and war. And during the Joseon Dynasty, attempts were made to overcome these disasters through Confucianism, which was the national religion at this time; however, Confucianism came up short in attempting to mollify the citizenry. Unable to do this, Korean Confucians turned to the Buddhist Water-Land Ritual. As a result, the Joseon court attempted to create social stability through the marginalized Buddhist practices.

The concept of hungry ghosts comes from the traditional Indian idea of “preta,” who are spirits of dead parents. This concept, in turn, was modified and combined with the Chinese notion of “gui – 鬼.” In China, this concept was related to the loss of ancestors and their memorial services. It was through the Chinese that these spirits came to have a grotesque-looking appearance that were made that way through hunger and thirst. Thus, the focus had changed from the loss of parents in India to memorial services being conducted in China. And this would then be changed, once more, to encapsulate not only the idea of ancestors and memorial services, but they would also come to represent those souls that had been trapped in a world of ignorance and desire. And one of the main reasons for their karma is that of miserliness. Of the seven kinds of suffering that agwi experience, and that the Seven Buddhas alleviate, it’s miserliness that gives the most cause for agony. It’s also the first quality to be eliminated, as well. This is where the central idea of desire comes from. Furthermore, hungry ghosts are considered to be even lower than animals on the Six Paths of Rebirth. So, in its totality, hungry ghosts came to represent the idea of salvation that was needed to be achieved through the Water-Land Ritual.

Visually, a hungry ghost is traditionally depicted as having a large body, since it represents a group of agwi. It also integrates the physical pain of the soul through the expression on its face. For this reason, it’s also called a “Burning-Face Ghost King.” This hungry ghost is also known in a Gamno-do as a Bijeung-bosal (A Bodhisattva Known for Extraordinary Compassion). According to ritual manuals of the Water-Land Ritual, a hungry ghost is a Bodhisattva who saves sentient beings on evil paths. And while hungry ghosts are depicted as being ghastly and scary, contorted and distorted by the actions and choices made in their former lives, they are also an incarnation of one that wishes for mercy. Another name for hungry ghosts is a “Burning-Face Great Being.” They are depicted in their grotesque form in order to seek companionship with other hungry ghosts in a state of intermediate existence. In essence, these hungry ghosts are a manifestation of the transformation of Bijeung-bosal that takes place during the Water-Land Ritual. Bijeung-bosal takes the form of a hungry ghost so as to save these spirits.

The very word “Bijeung” emphasizes the practice of compassion found in the intrinsic nature of a Bodhisattva. Depending on the methods of the Water-Land Ritual, and who is conducting it, Bijeung-bosal is sometimes described as either Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife) or Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion). But regardless of who the Bodhisattva might be, Bijeung-bosal suffers the same torment and hunger pain as the hungry ghosts. And it’s through this common act of suffering that Bijeung-bosal better understands these hungry ghosts and can better save them. So Bijeung-bosal has a dual purpose in the Gamno-do painting: first, Bijeung-bosal is the one that needs saving; and secondly, he’s the one that does the saving.

In the late 16th century, as the Gamno-do iconography was developing and evolving, there was only a single image of a hungry ghost. However, over time, and during the mid-17th century and onward, two hungry ghosts began to appear in Gamno-do. And by the 18th century, two hungry ghosts became a staple of the Gamno-do iconography. What’s interesting about this is that in 16th century Gamno-do there was only the sufferer; namely, the hungry ghost. However, as time passed, both a hungry ghost and a manifestation of Bijeung-bosal appeared in Gamno-do. This co-existence and inter-dependence highlights one of the central notions contained within a Gamno-do.

Finally, with the stability found in 18th century Joseon, there was no longer the pressing need for the Water-Land Ritual. However, the Water-Land Ritual continued. It continued for a few reasons. First, there was still the need to placate and console the souls of deceased ancestors by helping to send them off to paradise. And in return, those people participating in the Water-Land Ritual hoped for some form of financial compensation. The faith found in this ritual for the living was further accentuated by the increased grotesque appearance of hungry ghosts found in 18th century Gamno-do. By highlighting the horror and anguish of the hungry ghosts, there was greater need to help save those hungry ghosts that were living in a world of anguish. And by helping their ancestors, they hoped for an even greater reward as compensation in their present life.

Examples of the Gamno-do

In total, there are seven Gamno-do that are Korean Treasures. They include ones from Seonamsa Temple in Suncheon, Jeollanam-do (Joseon-era); Namjangsa Temple in Sangju, Gyeongsangbuk-do (1701); Ssanggyesa Temple in Hadong, Gyeongsangnam-do (1728); Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do (1723); Beopinsa Temple in Hamyang, Gyeongsangnam-do (1726); Seongjusa Temple in Changwon, Gyeongsangnam-do (1729); and Daegoksa Temple in Iksan, Jeollabuk-do (1764).

As for my own travels, I’ve only seen about ten to twelve of these ceremonial paintings. These temples and paintings include Unheungsa Temple in Goseong, Gyeongsangnam-do; Yeongsanjeongsa Temple in Miryang, Gyeongsangnam-do; Boseongsa Temple near Tongdosa Temple in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do; Anjeongsa Temple in Tongyeong, Gyeongsangnam-do; Naewonam Hermitage in Busan, Samhwasa Temple in Donghae, Gangwon-do; Sutasa Temple in Hongcheon, Gangwon-do; Bohyeonsa Temple in Gangneung, Gangwon-do; Geonbongsa Temple near the DMZ in Goseong, Gangwon-do; and Guryongsa Temple in Wonju, Gangwon-do.

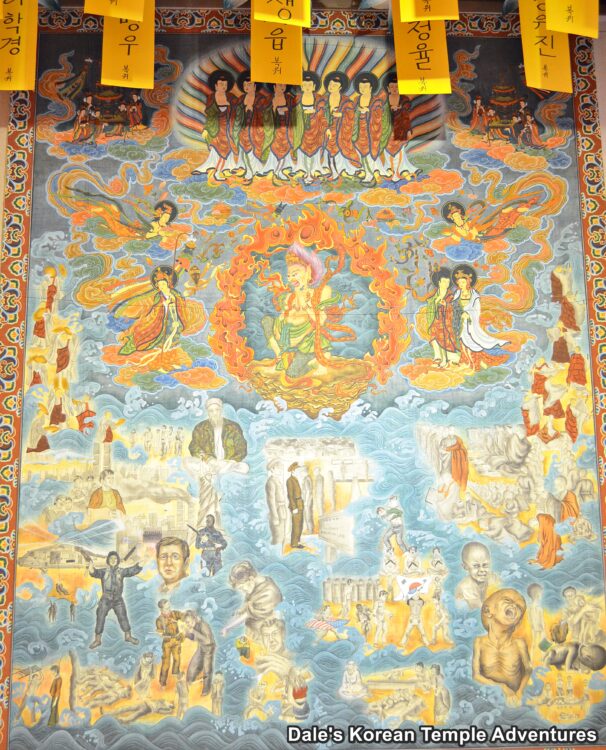

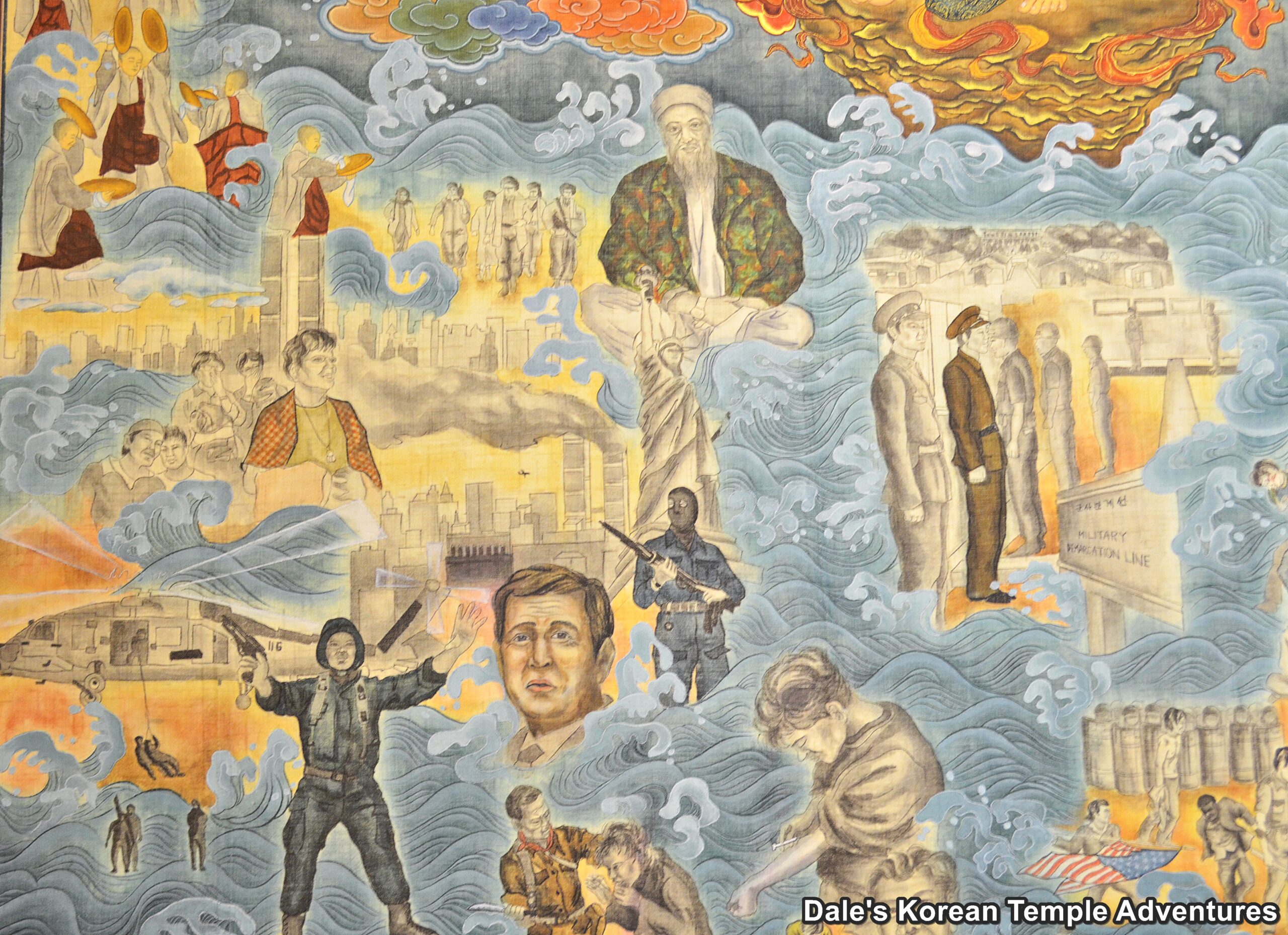

More specifically, and rather interestingly, Seongdeokam Hermitage in Masan, Gyeongsangnam-do has a modern twist on the classic design of a Gamno-do. The Gamno-do at Seongdeokam Hermitage follows the traditional form of a Gamno-do: it has three sections. The upper and middle sections follow the traditional standards of the genre with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in the upper section and with an agwi (hungry ghost) in the middle section. However, where the Gamno-do at Seongdeokam Hermitage diverges is in the bottom portion of the painting. Instead of realistically portraying the Six Realms of existence in some ancient or mythical scenario, the Gamno-do at Seongdeokam Hermitage is firmly rooted in the past fifty years of world history. More precisely, instead of having people that might look like they inhabit a world around a Goryeo or Joseon Dynasty time frame, we see images of those people that have shaped our world in the present. In the mural, rather remarkably, you’ll see painted images of Osama Bin Laden, George W. Bush, 9/11, the DMZ, the Vietnam War in the form of the famous picture of the national police chief of South Vietnam executing a Vietcong fighter, the Gwangju Uprising from May 18th to 27th, 1980, and the 1983-1985 famine in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

Overall, the Gamno-do has a dual purpose. The first is to console the spirits of the dead in the afterlife and free them from the pain that’s being inflicted on them by agwi. The second purpose of the mural is a warning for those that are still alive and the misdeeds they might be committing in their present life. And hopefully, the mural will act as a deterrent and help change people’s present ways.

In a world filled with disorder and chaos, it’s no wonder that the Gamno-do, or “Sweet Dew Mural” in English, attempts to illustrate the uncertainty surrounding death and the afterlife. It does this through the structure found in the division of the mural into three parts: the upper, middle, and lower sections. And while these three sections may appear independent of each other, they are all interconnected. These images depict the events that occur at each stage of the Water-Land Ritual. What can be confusing is the chronological order found within the painting and the multiple time periods captured within the mural. However, while the Gamno-do has a past, present, and future captured in the painting, they are all concurrently taking place. The bottom illustrates how the agwi is suffering in the afterlife. And the central image is in fact the agwi suffering in the present. While the upper portion of the painting depicts the salvation of the agwi through the Water-Land Ritual. Also of importance is the blending of the beautiful with the ugly. And through this, redemption and salvation can be achieved for anything and anyone. This is the very essence of the Gamno-do: salvation.