Hojak-do – Tiger and Magpie Painting: 호작도

Introduction

The “Magpie and Tiger” is a prominent genre of Minhwa in Korean folk art known as “Hojak-do – 호작도.” This painting is also known as a “Kkachi Horangi Minhwa – 까치호랑이 민화” in Korean. In this painting, the tiger is purposely given a ridiculous appearance, while the magpie looks more dignified and noble. So why are these two animals depicted this way? What is a Minhwa? And why do they appear at a Korean Buddhist temple?

Minhwa

The term “Minhwa” literally means “painting of the people” or “popular painting” and were originally from the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). The present form that we know of today in Minhwa art dates back to around the 17th century. As for the term “Minhwa,” it was first coined by Yanagi Muneyoshi (1889-1961), when referring to this style of painting at an art exhibition held in Kyoto, Japan in March, 1929. Later, in “Craft Painting” from 1937, Yanagi describes Minhwa as “paintings born by the people and drawn by the people.” Yanagi’s theory was first introduced to Korea in the Dong-A Ilbo newspaper, when he wrote an article entitled “The Surroundings of Korean Crafts” in October, 1939. And while this form of art was broadly introduced to the public at this time, it wasn’t until the late 1960s that the general public started to take notice.

Minhwa refers to Korean folk art that was traditionally created by unknown artists that were without formal training. These artists produced pieces of art that attempted to imitate contemporary trends in fine art whose origins were typically found in the palaces of royal courts for the purpose of everyday consumption. The artists that produced these Minhwa wandered around to festivals and created these pieces of art on paper or canvas for a fee on the spot for locals.

A Minhwa’s composition is both simple and bright, and it uses colours to convey its overall essence of daily life through symbolism. This symbolism conveys humour, wit, freedom, and unity as characteristics of Korean culture as a whole. And the way that this was done was through folk tales and legends.

Styles of Minhwa

In total, there are numerous genres of Minhwa folk art. They are:

1. Chaekgeori: stationary objects like books

2. Chochung-do: flowers and insects

3. Eohae-do: fish – meant to represent fertility and the warding off of evil in a bride’s room

4. Hojak-do: tigers, magpies, and pine trees

5. Hwajo-do: flowers and butterflies – meant to symbolize hope for love and harmony in a marriage as well as balance within a family

6. Ilwolbusang-do: the sun and moon over trees – symbolizes royal protection

7. Morando: peonies – associated with ceremonies, marriages, royal events and symbolizes honour and wealth

8. Munja-do: Chinese characters (hanja)

9. Sipjangsaeng-do: the ten symbols of longevity

10. Yongho-do: powerful animals like tigers and dragons – symbolizes protection from bad luck

11. Yunhwa-do: lotuses – symbolize noble characteristics along with fish, birds and insects. If a duck appears with lotus flowers, it’s meant to represent family happiness and marital love

Tigers and Magpies in Korea

Korea was once known as “the land of tigers.” However, tigers are now completely extinct in South Korea. Before, however, they could be found in the numerous mountains that dot the Korean Peninsula. Also, these tigers often came down from these mountains to villages, where they harmed people and their livestock. But while tigers were feared in Korea, they were also respected. That’s why tigers were often given the name of “prince of the mountain.”

The tiger also has a lot of historical and symbolic meaning in China and Korea. One belief in China has the tiger operate as one of the four directional guardians during the Spring-Autumn Period (770 – 481 B.C.) and the Warring States Period (475–221 B.C). As for Korea, the tiger is closely linked to Korea’s foundational myth and Dangun.

Magpies, on the other hand, are known as “joy bringing magpies” in Korea. The reason for this is that they are thought to bring good news and/or the arrival of a guest. In China, on the other hand, magpies are a sign of marital bliss. In the 4th century “Book of the Gods and Strange Things – Shenyi Jing,” the author, Dongfang Shuo (160 B.C. – c. 93 B.C.) narrates a story about the emergence of magpie mirrors during the Han Dynasty (202 B.C. – 9 A.D., 25–220 A.D.). In this story, a married couple is separated. They break a mirror and give each other one half of the broken mirror. According to this story, if the wife gives into temptation and has relations with another men, her half of the mirror would change into a magpie and fly back to her husband. That’s why mirrors were originally decorated with magpies in China. Additionally, twelve magpies denotes twelve heartfelt wishes, as well.

There is another tale related to magpies and the Qing Dynasty (1636–1912). The founding father of the Qing Dynasty, Hong Taiji (1592-1643), was fleeing from his enemies when a magpie perched atop his head. Since then, the magpie became a sacred bird to the Manchus.

Hojak-do Minhwa

Of the eleven genres of Minhwa, it’s the Hojak-do that this post will focus on. The name “Hojak-do” is a reference to the subjects in the painting: Ho/tiger, jak/magpie, and do/painting. And in this painting, a magpie sits on a pine tree branch, while the tiger typically looks up at it. The tiger has a ridiculously stupid appearance. The tiger is meant to symbolize authority and the aristocratic yangban class. The tiger appears in the centre of the painting, while the magpie is typically situated in the corner. The magpie is dignified and knowing in appearance. And there’s a Korean folktale that helps put this painting into context:

There once was a tiger that wandered into a big puddle in the forest. Incapable of freeing himself, the tiger anxiously awaited for someone to rescue him. He endured days without a meal before a good-natured woodcutter happened to pass by the muddy puddle and the tiger. The tiger begged the man to save his life. When the woodcutter obliged, the ungrateful tiger attempted to eat the woodcutter. Startled by this sudden turn of events, the woodcutter asked an ox and a pine tree to fairly judge the situation. But the pair sided with the tiger, urging the tiger to eat the woodcutter.

In desperation, the woodcutter turned to a magpie for its opinion and final judgment. The magpie asked the woodcutter and the tiger to re-enact the story so that he could make a proper judgment. The foolish tiger returned to the puddle and got stuck, once more. The woodcutter was freed.

What this folktale and painting are meant to symbolize is a satirical look at the strict social hierarchy and norms at that time during the Joseon Dynasty. The tiger is meant to represent aristocratic officials who often mistreated commoners (subjects). The magpie, on the other hand, looks down on the tiger from its pine tree perch. The magpie is mocking the tiger.

The relationship found between tigers and magpies was first established when Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) tiger paintings migrated eastward to Korea. In the 17th century, Ming Dynasty tiger paintings would sometimes have magpies appear in the background. At this time, there was no significant role given to the magpie. With that being said, most of these Ming Dynasty tiger paintings were set against a magpie and a pine tree. The Joseon Dynasty’s artist Kim Hong-do (1745-1806?) re-interpreted the tiger. Kim would present the Ming Dynasty’s dominant realism with that of a Korean reinterpretation of social class.

Examples of Hojak-do Minhwa

There are numerous examples of the Hojak-do Minhwa. One of the better known is the “Songhamaengho-do – Tiger under the Pine Tree” by Kim Hong-do (1745-1806?). In this painting, the tiger’s tail is raised, and its face is turned. The tiger’s eyes are yellow, and it looks as though it’s about to pounce. However, the magpie is absent in this painting. Unlike Ming paintings of this genre, the background is simplified. It’s also worth noting that it’s in the 19th century that the presence of the magpie becomes more popular in this genre of paintings.

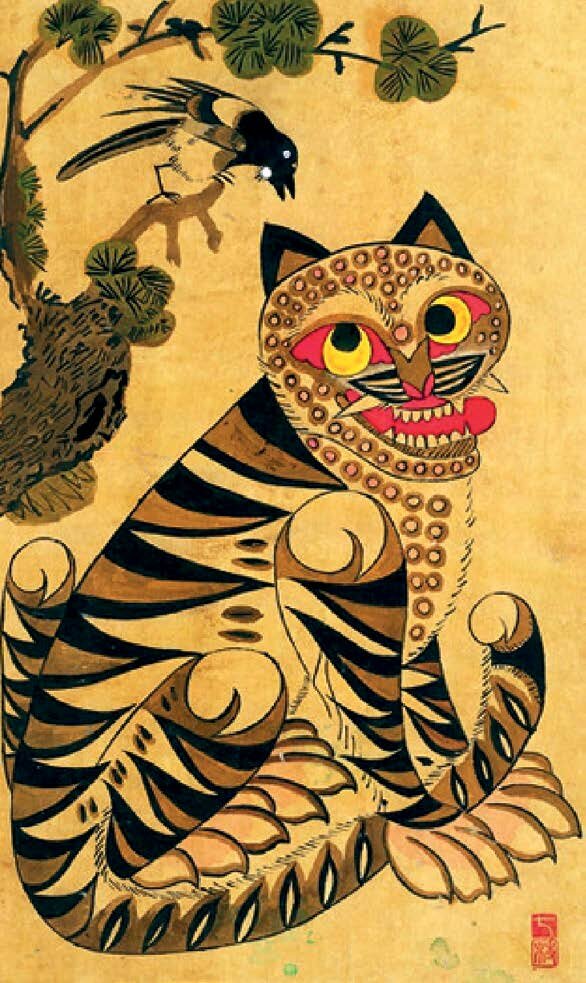

Another renowned painting is the “Tiger and Magpie” Minhwa drawn by an anonymous artist during the Joseon Dynasty. In this Minhwa, the tiger has shining yellow eyes, and the tiger’s mouth is open threatening the magpie on the neighbouring branch. The magpie stands high in the pine tree with its tail upright in defiance of the tiger. It almost looks as though if the tiger jumps the magpie will simply fly away.

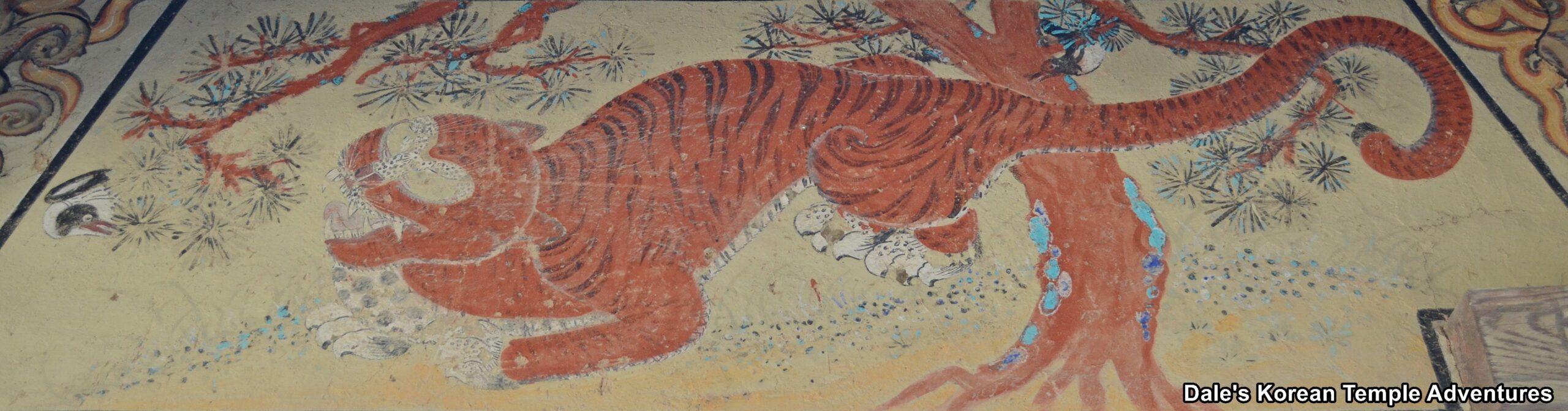

And while these Minhwa are well-known throughout Korea, they are not as easy to find at Korean temples. There are exceptions, however. One of these examples can be found at Tongdosa Temple on the right exterior wall of the Haejangbo-gak Hall. In this painting, the tiger, once again, takes a central position in the painting. But unlike other traditional paintings, there are in fact two magpies. There is one at the head of the tiger and one at its tail. Both are perched in the same pine tree. The one near the tiger’s head looks like it’s ready to take flight from its precarious branch, and the tiger looks ready to lunge. As for the magpie that stands securely in the pine tree by the tiger’s tail, it looks ready to distract the tiger from its ultimate goal.

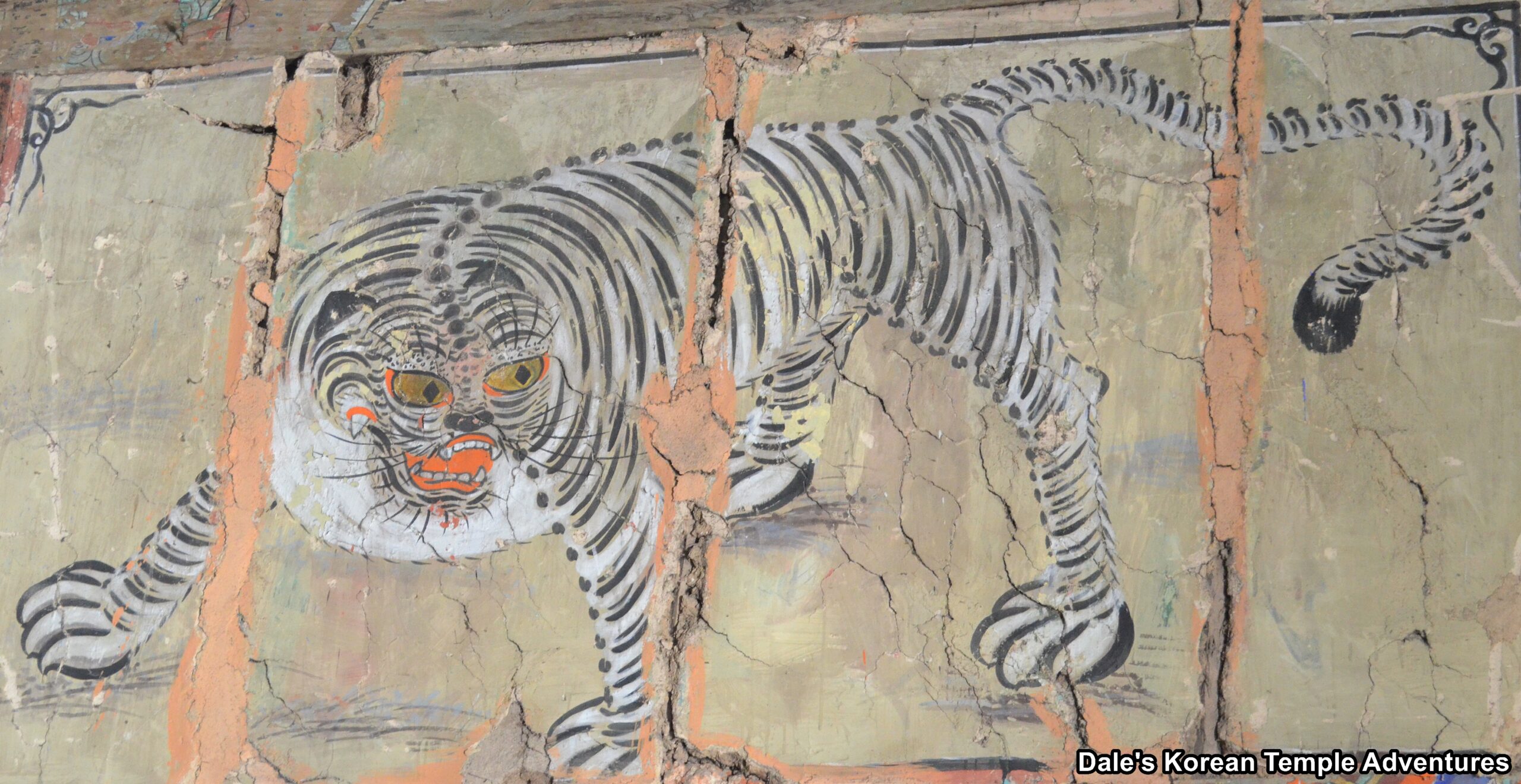

Another example of this genre can be found inside the Myeongbu-jeon Hall also at Tongdosa Temple. In this painting, the tiger is white and is, once again, placed in the centre of the painting. To the right of the tiger is a pine tree with two twisting trucks to two separate pine trees that are now intertwined. And above the white tiger’s head are a pair of magpies that look down on the unsuspecting tiger that’s looking away from the two magpies in the wrong direction.

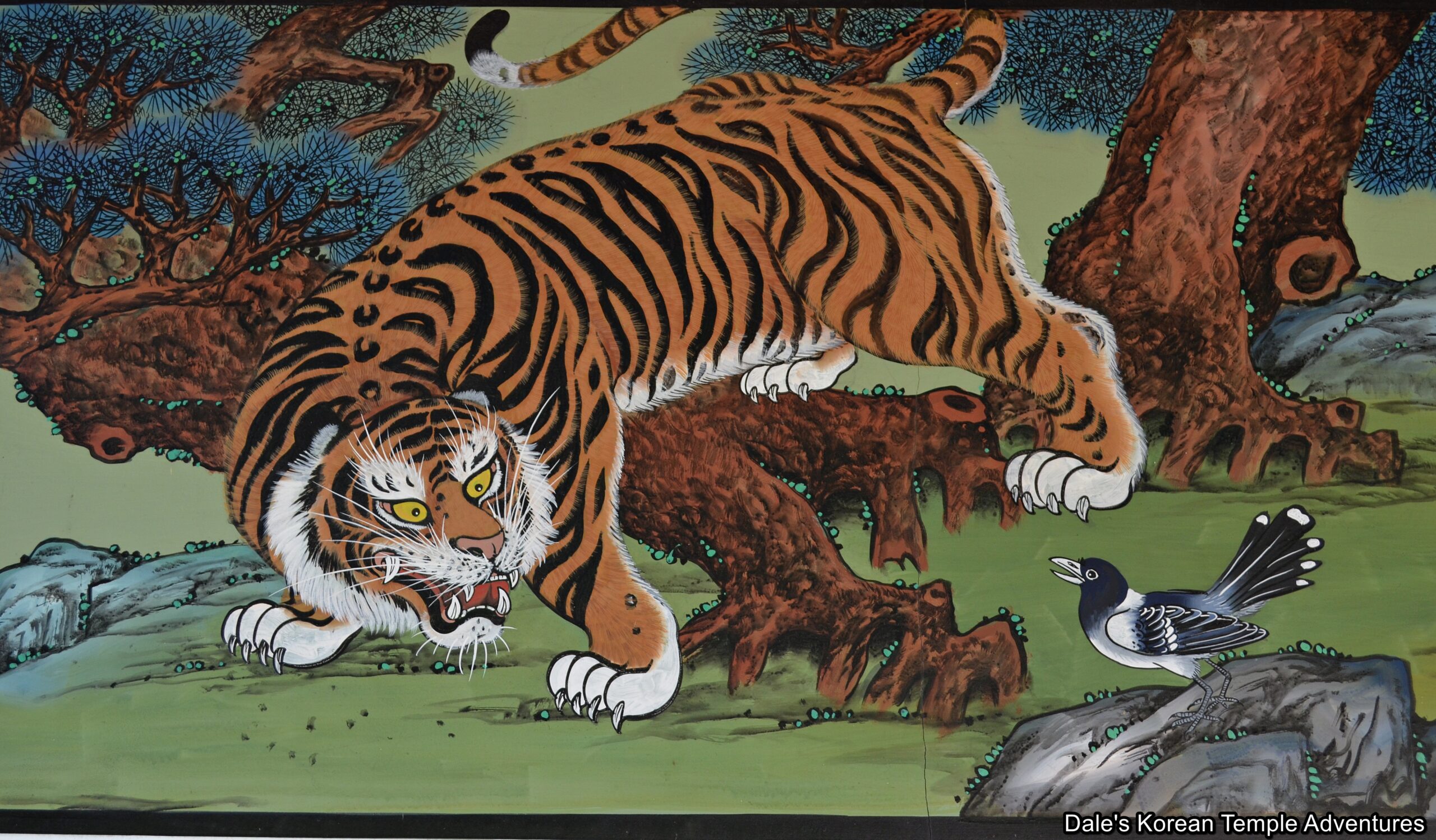

Yet another example can be found on the right exterior wall of the Samseong-gak Hall at Talgolam Hermitage on the Beopjusa Temple. Once more, the rather fierce-looking tiger takes up the central position in the painting. The tiger steps over the trunk of the pine tree with it right hind leg. And instead of being up in the safety of the pine tree, the magpie appears ready for a chat with the tiger with its mouth wide open on a neighbouring rock.

One further example, and a play upon the original at Sinwonsa Temple, is the male-female Sanshin (Mountain Spirit) at Geumryongam Hermitage on the Sinwonsa Temple grounds. In this painting, the spotted tiger looks up quizzically at the magpie perched above its head on a pine tree. Perhaps because of the female Sanshin in front of it, the tiger looks more sedate and more tolerant of the magpie than it usually would be. The magpie looks in the opposite direction of the tiger as though it’s not all that concerned with the feline’s presence.

Conclusion

The Minhwa folk art tradition is a beautiful style of painting that is quite diverse in its subjects and symbolism. At the very heart of this tradition is the ever popular “Tiger and Magpie” painting. While extremely popular throughout the centuries, it’s harder to find at a Korean Buddhist temple. But its presence at a temple makes sense, especially if one considers the popularity of Buddhism with commoners during the Confucian-oriented policies of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), when these Minhwa paintings grew in popularity. Buddhist temples helped satiate the growing spiritual needs of the Korean people during this tumultuous time in Korea’s past. So it’s no wonder that the “Tiger and Magpie” paintings would start to appear at Korean temples during the Joseon Dynasty to help support commoners, while poking fun at the alleged misguided policies of the ruling class.