Shinjung Taenghwa & Dongjin-bosal – The Guardian Mural & The Bodhisattva that Protects the Buddha’s Teachings: 신중탱화 & 동진보살

Introduction

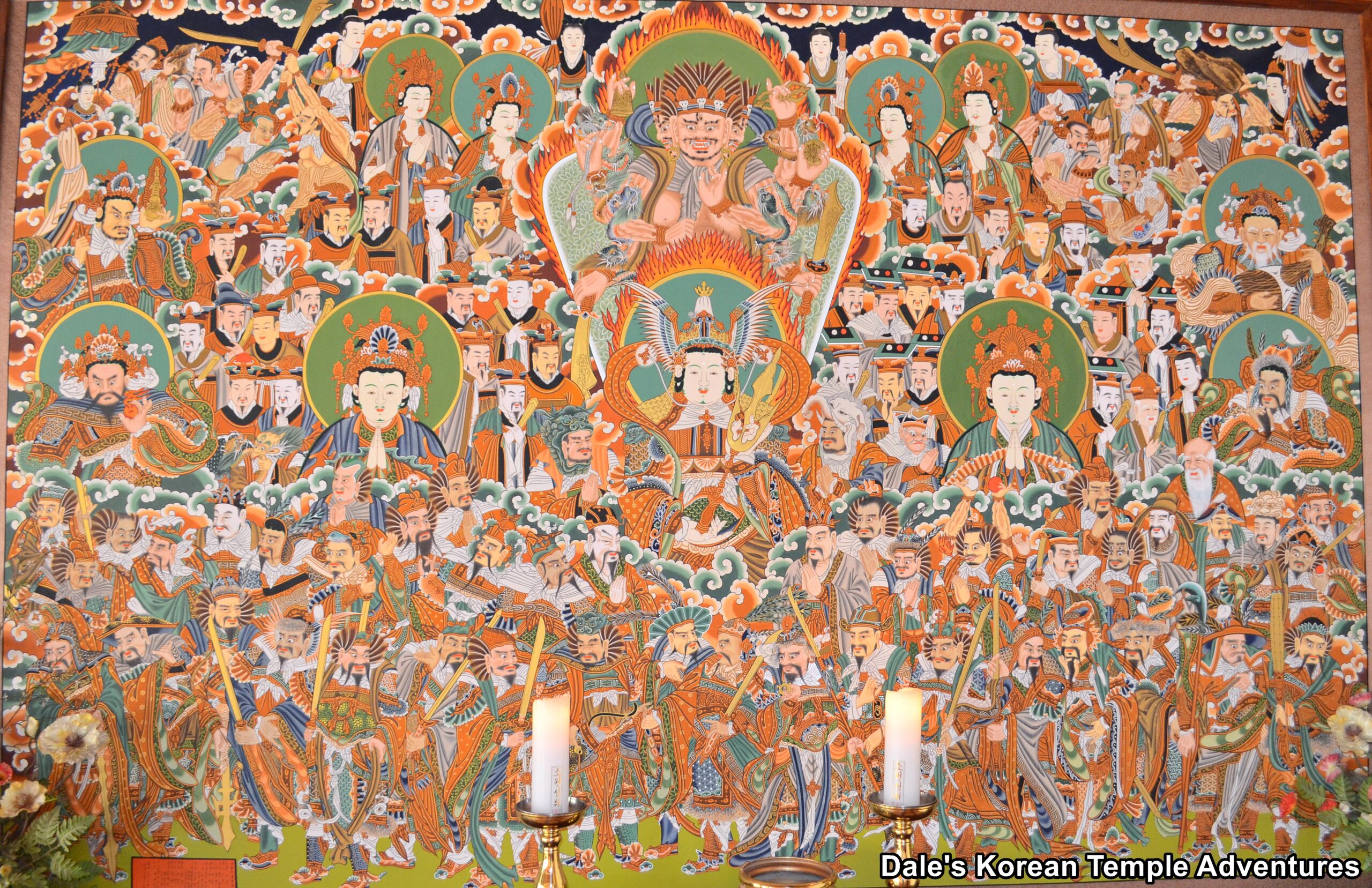

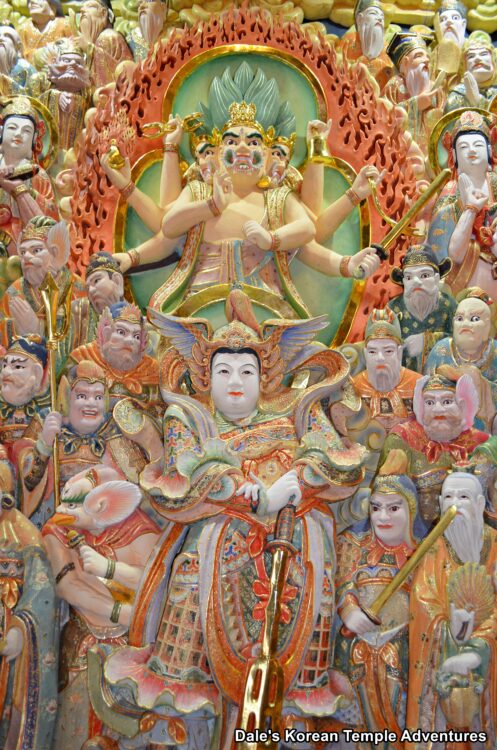

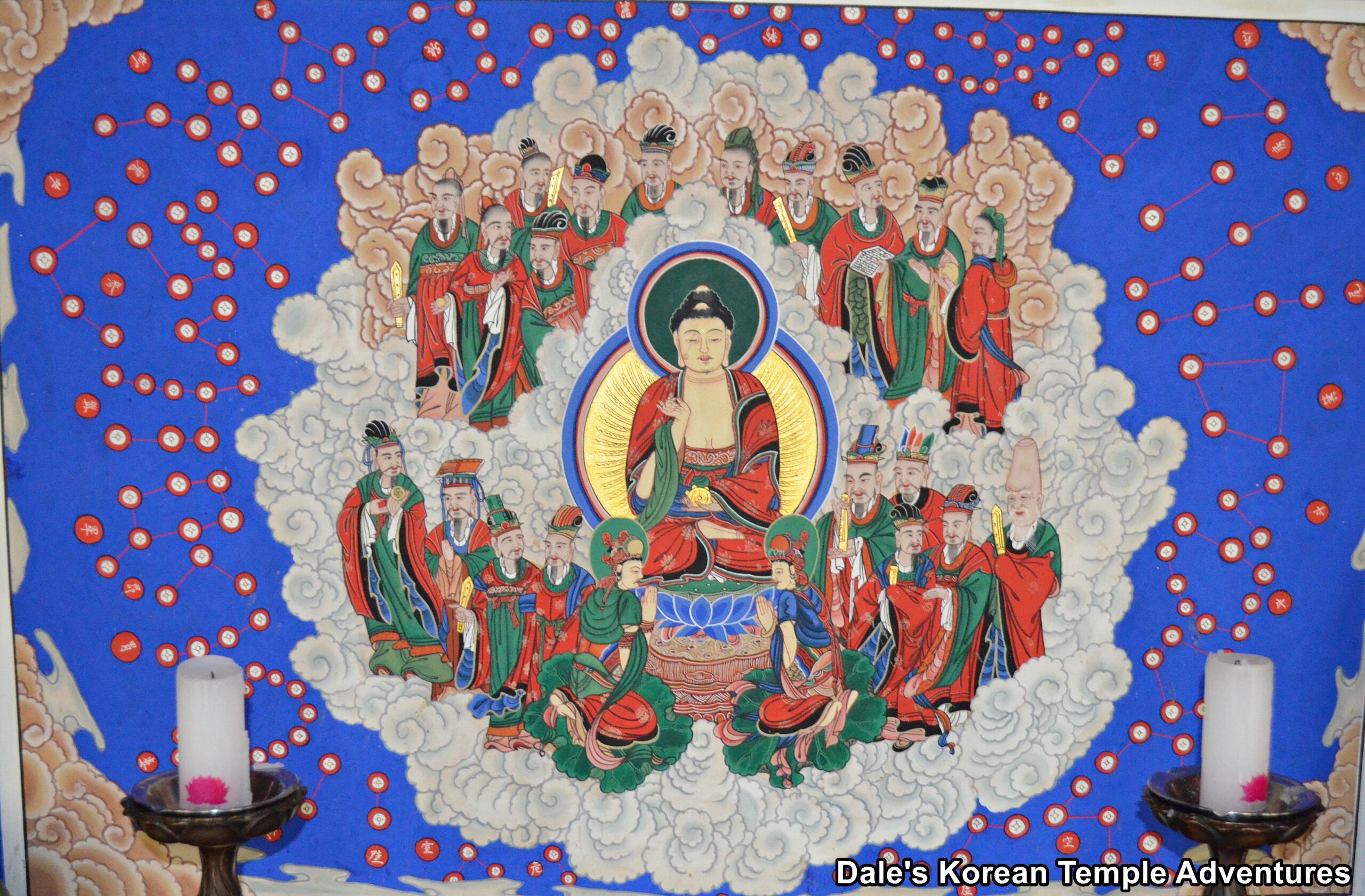

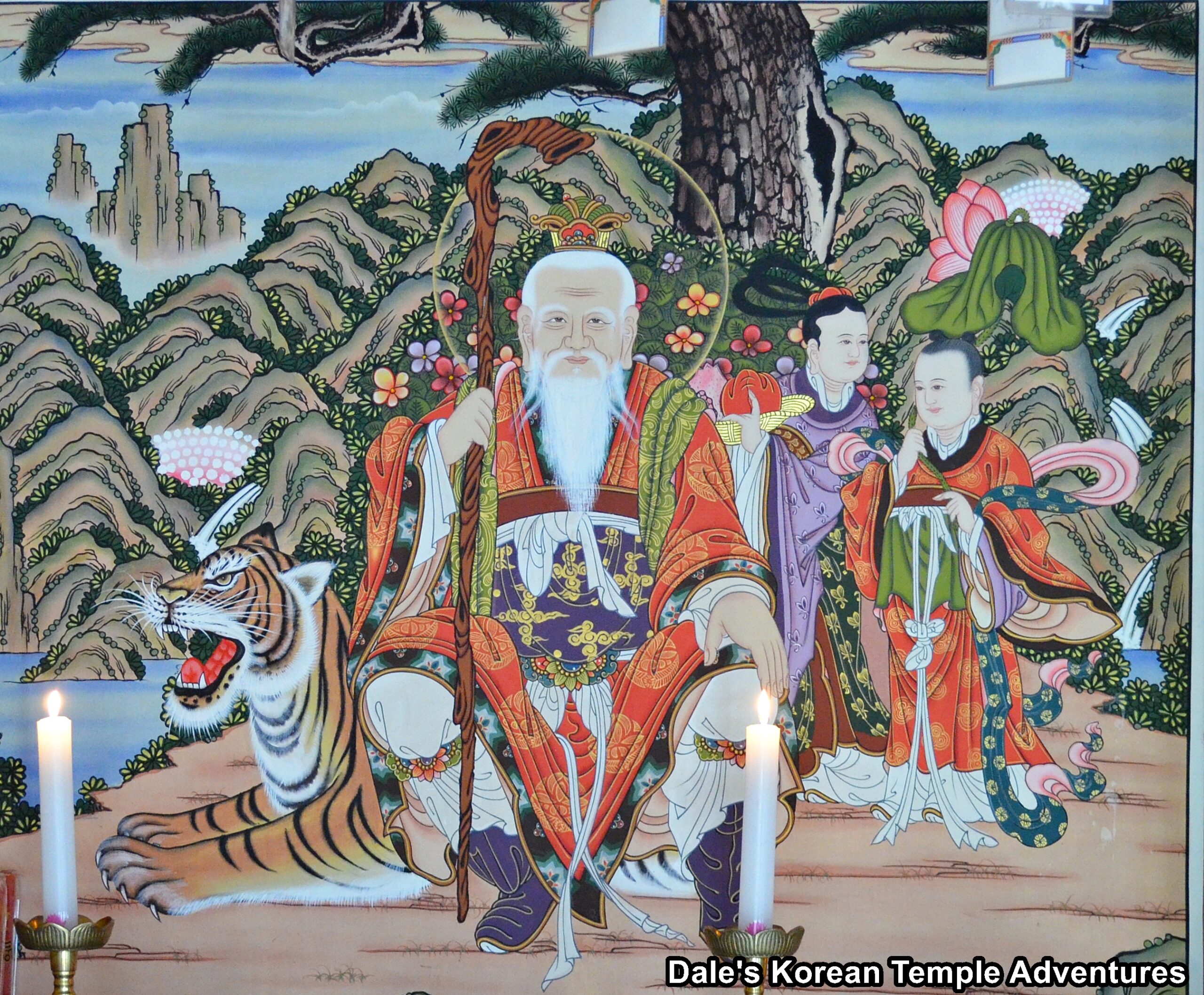

The Shinjung Taenghwa is one of the most popular murals that you’ll find at a Korean Buddhist temple. In English, the Shinjung Taenghwa means “Altar Painting of Guardian Deities,” or the “Guardian Mural” for short. This mural is highly intricate. So what exactly does a Shinjung Taenghwa look like? Where can you find it? Whose in it? And what does it all mean?

The Placement of Shinjung Taenghwa

Inside the Daeung-jeon Hall at a Korean Buddhist temple, you’ll find a Shinjung Taenghwa on the right side of the main hall. This side of the wall is called the middle altar within a division of three altars inside the Daeung-jeon Hall. The upper altar, which houses the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, is called the “sangdan” in Korean. The middle altar, where you’ll find the Shinjung Taenghwa, is called the “chungdan” in Korean, which houses other deities. And the lower altar, which is known as the “hadan” in Korean, is an altar for the dead.

This three-fold division of altars inside a Daeung-jeon Hall also helps explain the hierarchical nature found between different shrine halls at a Korean temple. For instance, those shrine halls that house non-Buddhist deities like Sanshin (The Mountain Spirit) and Chilseong (The Seven Stars) all belong to the lower section of this division, the “hadan.” This three-fold relationship within a Korean Buddhist temple and Daeung-jeon Hall first started during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).

Near the end of the Joseon Dynasty, the Shinjung Taenghwa (and the deities housed inside this mural) enjoyed a renewed surge in popularity. This may seem a bit contradictory, since this was a time when Korean Buddhism suffered doubly; first by the marginalization found in the Neo-Confucian state, as well as an increasing demand for Buddhist reforms. So what is a Shinjung Taenghwa? Which deities are depicted in it? And why is it so important? All those questions start with the central image in the Shinjung Taenghwa: Dongjin-bosal (The Bodhisattva that Protects the Buddha’s Teachings).

Indian Origins of Dongjin-bosal (The Bodhisattva that Protects the Buddha’s Teachings)

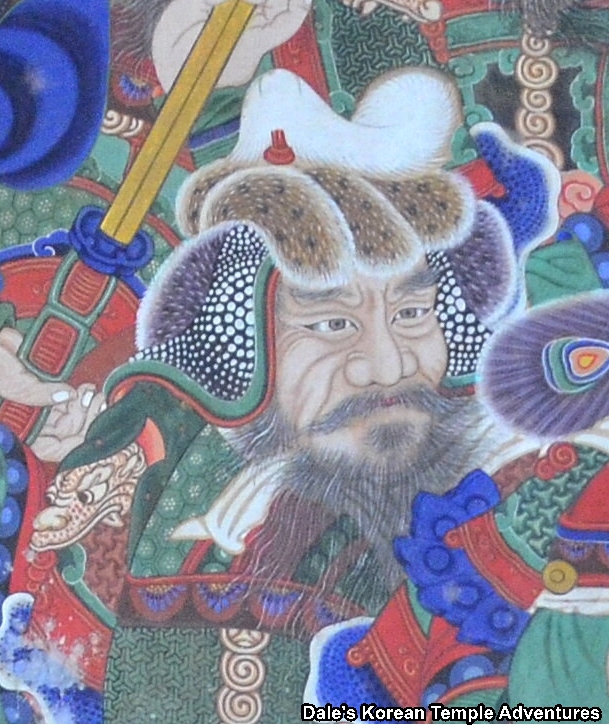

The central figure in a Shinjung Taenghwa is the winged-helmet deity known as Dongjin-bosal in Korean, or Skanda (Kartikeya in Sanskrit). So how did this deity come to appear in the middle of such an important mural in Korean Buddhism? We need to go all the way back to pre-modern India to trace Dongjin-bosal’s origins.

Because Skanda (Dongjin-bosal) has such a complex and diverse background, it’s hard to completely understand Skanda’s origins. The origin and worship of Skanda was developed around countless local variants in different regions over a long period of time. As such, it’s very difficult to construct a simple linear history of this multifaceted deity. The earliest written records on Skanda are found in the Mahābhārata (ca. 400 BCE and ca. 400 CE) and Rāmāyaṇa (ca. 400 BCE). However, both texts lack a definitive answer as to where Skanda originates. Some have argued that Skanda was first worshiped in North India, while others have argued that Skanda first originated in South Asian local yaksha (nature spirit) cults.

It appears as though the origins of Indian Skanda worship grew out of the need to guard against child-attacking/pregnant women-attacking demons known as Graha (graspers) and Matr (mothers) in northern India. In this sense, not only was Skanda a demon who attacked children and mothers, but Skanda was also the leader of the Grahas (“grabbers,” “graspers,” or “seizers”) and other malevolent spirits like the pramathas (“tormentors”), bhūtas (“evil spirits”,) and prśācas (“blood suckers”). In fact, and according to one Indian medical encyclopedia, which dates back to the 6th century, Skanda is one of the nine Grahas.

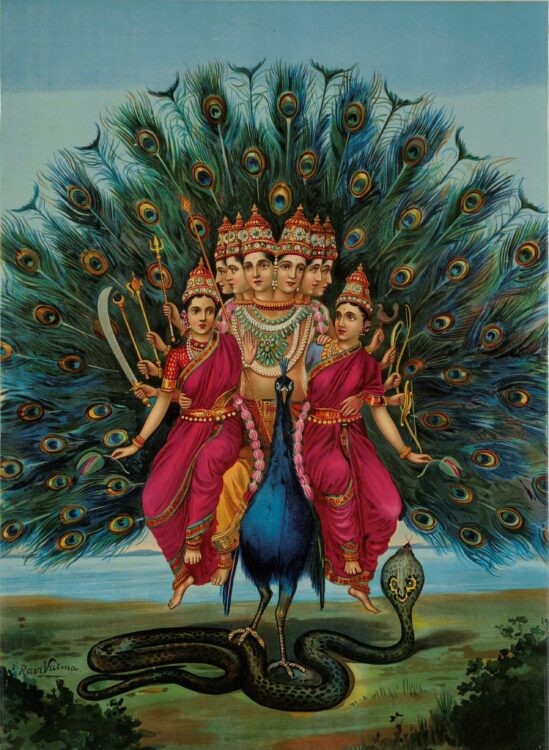

The change from this child-attacking demon was a slow process. And it should be noted at this point that the reason that Skanda (Dongjin-bosal) has a child-like face comes from these North India origins. During this process of change, Skanda would become a prominent warrior god identified as the son of Shiva/Maheśvara (or sometimes Agni) and the half-brother of Ganesha.

This process of change took over 500 years starting in the 1st century B.C. and continuing to the 4th century, when local Skanda cults were absorbed into Brahman traditions. With this being said, it shouldn’t be believed that this transformation was smooth or even linear. And it’s also from this period of time that the earliest image worship of Skanda dates back to around the third to second century B.C.

Back in North India, for instance, once Skanda had shed its demonic character, Skanda’s worship started to decline from between 500-750 A.D. But with Skanda’s decline in the north, his cult continued to spread throughout South India under the name of Murugan. In fact, a statue in the Tamil region was created as early as the 7th century. And today, in India, Skanda is mostly worshiped in the southern parts of India and less in the north.

With these cultic origins in mind, there are numerous other origin stories related to Skanda in Indian literature. For instance, in the Mahābhārata (Sanskrit epic poem) alone there are three different accounts of Skanda’s birth. The first of these accounts chronicles Skanda’s child-attacking demon origins. However, by the end of this first account, Skanda is described as the son of Shiva and Agni. Skanda is also a respected warrior deity at this point, as well. In In the Kumārasaṃbhava (“The Birth of the War God”, fifth century A.D., an epic poem by Kālidāsa), we discover more details as to how Skanda received his name. According to this poem, Skanda was born to destroy the asura demon Taraka (“he who delivers”), who could only be killed by a son of Shiva. We also get a bit of a graphic explanation as to how Skanda specifically gained his name. Skanda was born of Shiva’s sperm, which was deposited into the fire god, Agni. This is why Skanda has this name, which means “spurt of semen.” Skanda has another significant mythological connection with Agni and Ṣaṣṭhī. Svāhā (the personified invocation that accompanies any oblation to the gods) collected Agni’s seed six times in her hand and brought it to the White Mountain, covered by a forest of reeds. Skanda was born out of it with six heads that reached adult size by his sixth day of life. Skanda’s myth is further elaborated in later periods in the Purāṇa literary works such as the Shiva Purāṇa, the Brahman Purāṇa, and the Skanda Purāṇa, whose texts mostly illustrate the birth of Skanda from Shiva’s (or Agni’s) sperm and his role as a martial god.

What’s most important about these origin stories is that Skanda is the son of Shiva. Additionally, Skanda is the leader of generals, which becomes a dominant motif for this deity. Lastly, while Skanda has his origins in childhood disease and attacks as a demon; over time, this would change, where Skanda would eventually be recognized as a benevolent deity to whom people prayed to for the well-being of their children.

In addition to his patrilineal and matrilineal lines through Shiva and Agni, we also have Skanda’s half-brother Ganesha. This elephant-headed older brother shares the role as guardian of the gate with Skanda. With this coupling at a gate, Skanda came to be known as a protector, as well. And it’s with this link that Skanda later comes to be associated with Vajrapani, or “Geumgang” in Korean. It’s also from Ganesha that we get the swiftness for which Dongjin-bosal comes to be later known. In this tale, Shiva and Parvati (Shiva’s wife) tells their two sons that whoever can run around the world the fastest would get married. And while Skanda was faster in terms of sheer speed, Ganesha won the race because he ended the race with the proper ritual, which was a salute to both of his parents with seven circumambulations. This fast-running aspect and celibate nature of Skanda will become integral features of the deity’s development in Korea.

Dongjin-bosal’s Introduction to China

As for the transformation of Skanda from a purely Indian deity into a more Sino-fied form starts in the 5th century depictions of Skanda from the caves in Yungang. This is the earliest image of Skanda in China. One of the images in the Yungang caves is found in a relief on the eastern doorjamb of the entrance to Yungang Cave 8 (from the second half of the fifth century). What is fascinating about this image is that it forms a pair with Mahesvara, who appears on the western doorjamb. There is another symmetrical pairing between the father and son that appears in a relief above the doorway of Yungang Cave 10. These two pairings suggest Skanda’s popular role as the guardian of the gate. In these Yungang examples, we can see that sometimes Ganesha and Mahesvara become interchangeable as a partner to Skanda, while Skanda is firmly identified as the deity of the gate.

As to the exact time that Skanda was first introduced to China is unclear. However, by the Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.), Skanda is known in Chinese Buddhism. However, it isn’t until the Song Dynasty (960-1279) that Skanda becomes fully integrated and incorporated into the Chinese Buddhist tradition. And because Skanda had numerous names in India like Kartikeya, Subrahmanya, Shanmukha, and Murugan, it gave rise to a variety of Chinese translations to this deity with the most common being Weituo, or General Wei (Ch. Weijiangjun).

Initially, when Skanda was first introduced to China, he was the chief general of the Eight Generals of the Four Heavenly Kings (Kor. Sacheonwang). One of the earliest textual references to Skanda/Weituo in Chinese Buddhism is a translation by Dharmakṣema’s (385-433 A.D.) of the Nirvana Sutra; for which, Skanda/Weituo is one on a list of various deva deities. Skanda’s name also appears in the influential text, the Golden Light Sutra (Ch. Jinguangming jing). In this key text, Skanda is recognized as one of the protective deities found in Buddhism.

While these texts introduced Skanda to China, Chinese Buddhism quickly began to re-imagine Skanda/Weituo in their own language and imagination. This can be found in texts such as the “Fayuan zhulin” (a Buddhist encyclopedia compiled by Daoshi in 668 A.D.) and the “Daoxuan lüshi gantong lu” (“The Record of the Miraculous Communication to the Vinaya Master Daoxuan”).

More specifically, the “The Record of the Miraculous Communication to the Vinaya Master Daoxuan” is one of the central Chinese Buddhist texts responsible for the formulation of the legends that surround Weituo (Skanda) and his worship throughout China (and the rest of East Asia, for that matter, in later centuries). The text is attributed to Daoxuan (596-667 A.D.), the founder of the Nanshan School of the Vinaya School in China. This text led to a significant development of Weituo (Skanda) in China. Even though the association found between Daoxuan and Weituo in the text is a legend, the text helps to create a connection between the antiquity of Chinese Buddhism by introducing mythic accounts of figures like Skanda into ancient China.

Furthermore, the text gives several mythic accounts related to Weituo and Daoxuan. One of the most noticeable aspects of Skanda’s “conversion” to Buddhism is that he embodies Buddhist austerity. According to this text, Weituo symbolizes the eternal youth of immortality free from aging and, more significantly, that he maintains celibacy in perpetuity, which is expected of devote Buddhist monks and nuns. As seen in his earlier Indian myths, Weituo (Skanda) never married. Since celibacy was highly celebrated for the Buddhist monastics and those who advocated the strict observation of vinaya or monastic regulations, it would make sense as to why this particular aspect of Weituo appealed to Buddhist monks. This very association between Weituo and vinaya remained strong in the later periods, particularly within the Chan/Seon Buddhist tradition.

In addition, and it’s another significant part of the text, is Weituo’s connection to the relic cult in Buddhism. By the Song Dynasty (960–1279), Weituo was widely known as the deity who protected the relics of the Buddha. Weituo’s protection was also not limited to the physical relics of the Buddha; but instead, all aspects of Buddhism like the dharma and sangha, as well. This could specifically be seen in Weituo appearing both at the beginning and end of printed texts. This had two important meanings. First, the text was guarded by Weituo, but it was also a precious relic that contained the Buddha’s teachings. This idea of including Weituo follows a legend that states that Daoxuan wrote a preface to the Lotus Sutra, in which he included the image of Weituo. As such, it became a common practice to include the image of Weituo in newly produced copies of the Lotus Sutra.

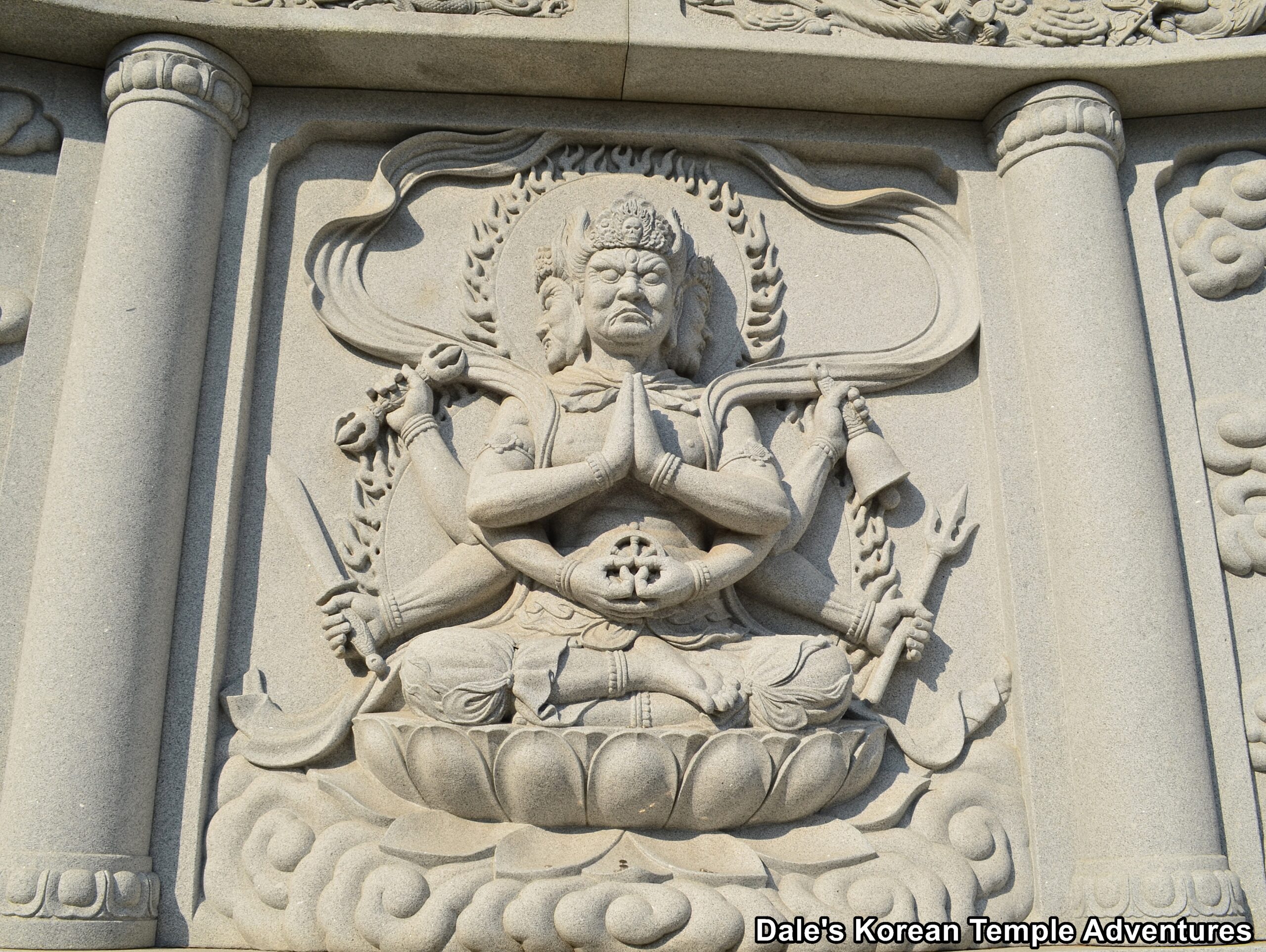

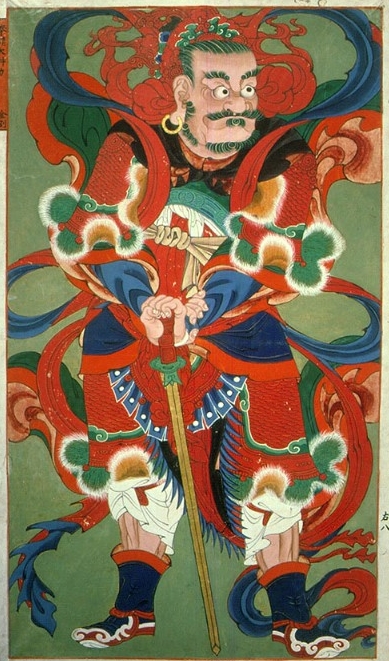

It’s also at this time during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) that Weituo becomes a prominent deity in Chinese Buddhist ceremonies. As such, Weituo is included in major ritual manuals of this time period. One such ritual manual was entitled the “Zhongpian zhutian zhuan,” which was compiled in 1173 by Xingting. This ritual manual states that Weituo is one of the twenty prominent deities that protects Buddhist rituals. Another very significant aspect to this ritual text is that it’s one of the earliest accounts of what Weituo looks like in detail. And according to this ritual text, “[Weituo] is a youth who wears a golden helmet holding his weapon horizontally across his forearms.” This will become the standard image of Weituo in China and beyond in East Asia.

Before moving onto Weituo/Skanda’s and his move to the Korean Peninsula, it’s important to further discuss other aspects of his change in appearance from India and onto China because this will have importance to Weituo/Skanda’s appearance in Korea, as well. For instance, in India, Skanda has multiple heads and arms; while in China, Weituo is a boy with only one head and two arms. Also, the youthful Indian warrior Skanda holds a spear and often rides a peacock. However, the peacock, arguably Skanda’s most distinctive feature, is gone by the time he becomes Weituo. The reason for this is that while a peacock and its feathers are widely seen as symbols of royalty and wisdom in Indian religions, the peacock in China isn’t necessarily seen as the most sacred. Also, and except in Yunnan Province, peacocks aren’t native to China.

But from the peacock and its feathers, we get one of the most noteworthy aspects and features of Weituo. Instead of riding a peacock, Weituo wears a distinctive winged helmet. This is an important visual cue that separates Weituo from other deities. Also, and it should be remembered from Skanda’s race with his brother Ganesha, the helmet highlights the swift speed of the deity like a bird.

Another interesting aspect of change in Skanda/Weituo’s appearance from India to China is the armour that Weituo will wear. It’s unclear and unknown how Skanda underwent this transformation, but it does seem to parallel the changes that the Four Heavenly Kings (Kor. Sacheonwang) underwent. For example, in India, the Four Heavenly Kings wear a type of sarong known as a dhoti and a turban. However, when the Four Heavenly Kings arrived in Central Asia, they come to be adorned in armour. This would then change to Chinese-style armour in Tang China. The reason for this is the war-like posture and nature of Tang China at this time. And given the similar role that both Skanda and the Four Heavenly Kings play in Buddhism as protectors, it can naturally be seen the need for such a change by the two kinds of deities in China at this time.

Another interesting aspect to Skanda’s appearance compared to that of Weituo’s is that Skanda holds a spear, while Weituo can hold a Vajra staff, a sword, or even a trident in his hands. Also in Chinese depictions of Weituo, he sometimes leans on his weapon, while at other times he presses his palms together reverently while his weapon lies horizontally across his forearms. This image of Weituo came to be widely reproduced during the Song Dynasty (960–1279) and has visually dominated the depiction of Skanda ever since including his appearance in Korean Buddhism.

The Arrival of Dongjin-bosal to Korea

Weituo, and the worship of this Buddhist deity, would arrive on the Korean Peninsula some time during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). This was probably through the frequent commercial exchanges between the Goryeo and Song Dynasties. In Korea, Weituo is known as Witaecheon; or more commonly, as Dongjin-bosal. Initially, the Goryeo worship of Weituo was heavily influenced by Chinese practices. As such, the visual representation of Weituo was similar to its Chinese equivalent.

The earliest extant images of Weituo/Dongjin-bosal are found in two forms: wooden block images found in Buddhist texts (roughly 80 extant examples), as well as illustrated copies of sutra texts (roughly 59 extant examples). Of the earliest visual examples of Weituo/Dongjin-bosal, they are found in wooden block prints of the Lotus Sutra, which describes the “Assembly of Seokgamoni-bul Preaching at Vulture Peak” that dates from 1286. Outside the Lotus Sutra, the earliest extant images of Dongjin-bosal appear commonly at the beginning and ending of other texts like the Diamond Sutra and the Avatamsaka Sutra from both the Goryeo and Joseon Dynasties.

Over time, Dongjin-bosal would come to appear at the centre of paintings with a crowd of other deities surrounding him. While in Chinese examples of Weituo, he is often depicted alone in a painting or paired with another popular deity or Bodhisattva like Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion); it’s rare to see Dongjin-bosal alone in Korea. Another common place to find Weituo is at a gate at Chan (Seon) temples with Budai (Kor. Podae-hwasang), who is a fat, jovial figure with a bald head. It’s believed that this male figure is a manifestation of Mireuk-bul (The Future Buddha). As for Japan, Dongjin-bosal/Weituo, who is known as Idaten in Japanese, is usually presented alone. This is especially true at Zen temples. While less popular than in China or Korea, when Idaten (Dongjin-bosal/Weituo) does appear at a Japanese temple, he’s typically alone.

And it’s to this distinction, the company that Dongjin-bosal keeps in Korean visual representations, that we turn to. Most commonly, Dongjin-bosal is found in a large assembly of images of deities called a Shinjung Taenghwa (Guardian Mural) in Korea. This large assembly of deities with Dongjin-bosal (Skanda/Weituo/Idaten) is unique to Korea.

A Shinjung Taenghwa belongs to a larger category of paintings known as a “taenghwa” in Korean. A taenghwa (ritual hanging painting) first appeared during the early Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). A taenghwa can take several forms including as a hanging scroll, a framed picture, wall-paintings, or large-scale paintings like a “Gwaebul” (Large Buddhist Banner Painting). But it was during the Joseon Dynasty, and Joseon Buddhism, that the taenghwa came to be the dominant form of Buddhist artwork that was used for visual rituals at the temple.

Visually, Dongjin-bosal is almost always the central figure in a Shinjung Taenghwa. And it’s through the pairings that we find Dongjin-bosal in a Shinjung Taenghwa that we are able to categorize the different styles of this Buddhist art form.

The first of these varieties, which is also the earliest, is the “Paintings of the Three Bodhisattvas,” or “Samjang Taenghwa” in Korea. This style of painting was produced for the rite of the “Deliverance of Creatures of Water and Land,” or “Suryuk-jae” in Korean, which is a ritual that originates in Song Dynasty China. The three Bodhisattvas are Cheonjang-bosal, Jiji-bosal, and Jijang-bosal. Each of the Bodhisattvas represents the heavenly realm, hell, and the human realm, respectively. In this painting, Dongjin-bosal appears as one of the disciples of Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife). While less dominant visually, which suggests a minor role in the ritual, the inclusion of Dongjin-bosal is significant because he’s invoked in the painting as a protector of the ritual. The inclusion of Dongjin-bosal in this style of painting has its origins in China. More specifically, we can find his name in the foremost “shuilu fahui” ritual manual, entitled “Ritual Proceedings for the Cultivation of the Feast of the Dharmadhātu Holy and Worldly Water and Land Majestic Assembly” authored by Zhipan (ca. 1220-1275). The text states that Dongjin-bosal along with other deities were invited at the beginning of the ritual to protect it, ensuring its success and efficacy. Additionally, by including Dongjin-bosal in the Korean “Samjang Taenghwa,” it allowed him to gain more devotees, leading Dongjin-bosal to be an essential member of the Shinjung Taenghwa by the 16th century. As such, Dongjin-bosal’s name continues to appear in ritual manuals starting at this time more and more frequently.

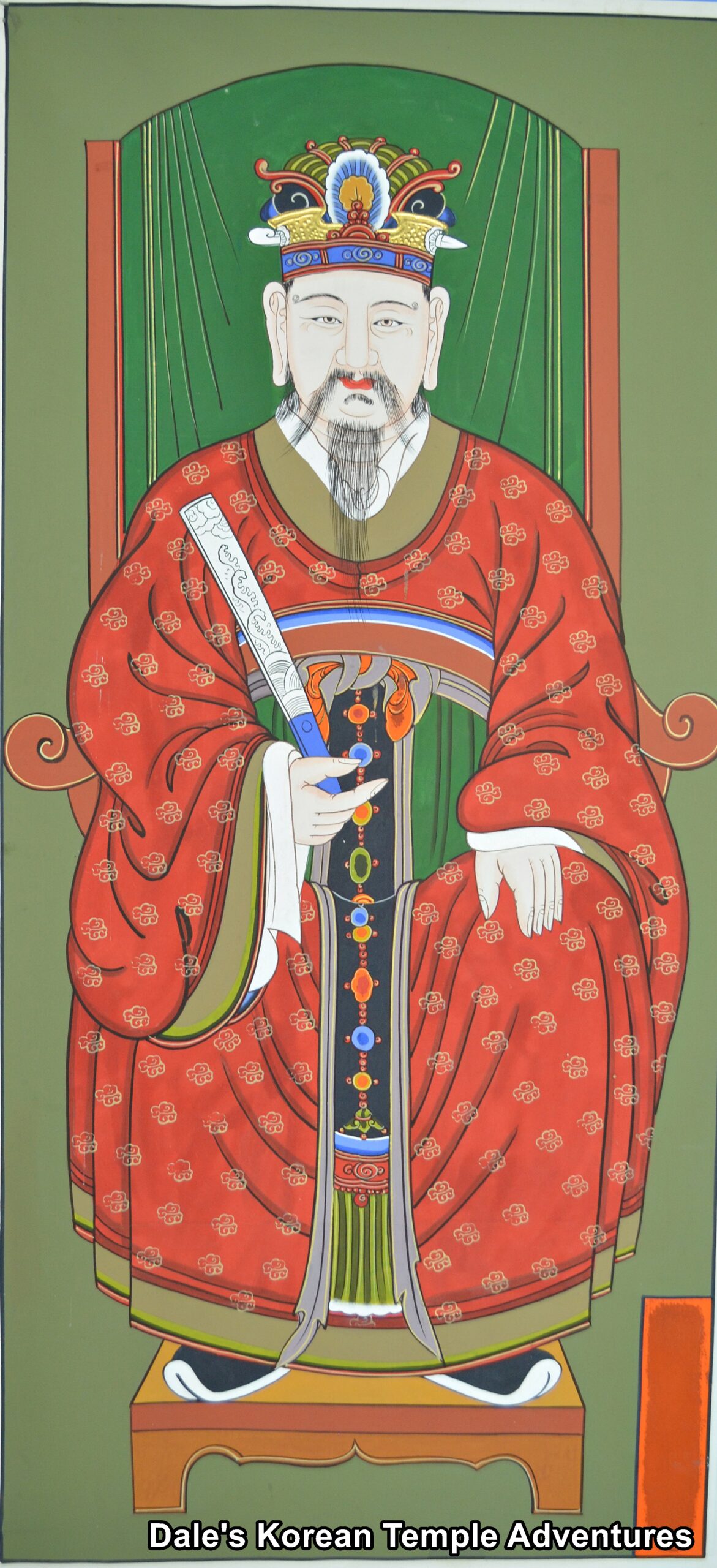

The second type of Shinjung Taenghwa has Dongjin-bosal paired with Jeseok (Indra). This pairing between Dongjin-bosal and Jeseok is the most popular combination found during the Joseon Dynasty. It’s also one of the earliest kinds of Shinjung Taenghwa with Dongjin-bosal as a central figure. Interestingly, Jeseok (Indra) in its Vedic form isn’t closely related to the origins of Skanda (Dongjin-bosal); instead, he’s his rival. However, in Korean Buddhism, Jeseok acquired an elevated status from the Goryeo Dynasty. The reason for this is that during the Goryeo Dynasty, Jeseok received royal support because the deity was believed to have the power to protect the nation. So the pairing of these two protectors together makes sense.

Eventually, this pairing would form a triad in the 18th century. Joining Dongjin-bosal and Jeseok in this triad was Beomcheon (Brahma). This triad came to be one of the most widely produced combination in the 18th and 19th centuries. In this triad, both Jeseok (Indra) and Beomcheon (Brahma) stand behind Dongjin-bosal with Jeseok and Beomcheon in the background and Dongjin-bosal in the foreground. What’s interesting about this triad is that Beomcheon is often perceived as a male deity, while Jeseok is depicted as female and Dongjin-bosal has a youth appearance. This reminds the viewer of the origin story of Dongjin-bosal (Skandra). In this case, Dongjin-bosal’s mother is Jeseok (Parvati) and Beomcheon (Shiva) is the father.

In the third type of Shinjung Taenghwa, Dongjin-bosal is found among the Eight Devas (deva, naga, yaka, gandarva, asura, garuda, kimnara, and mahorga). And in this setting, Dongjin-bosal is the leader of the Eight Devas. There are several variations of this grouping. In fact, in some groupings not all of the Eight Devas are present; instead, sometimes you’ll only find four or six of the devas with Dongjin-bosal. However, and no matter the number, Dongjin-bosal remains the leader and is almost always placed in the middle front of the painting. There is a lack of textual references for this grouping; however with that being said, the Eight Devas and Dongjin-bosal are almost always given and portrayed in protective roles. So the grouping of the Eight Devas and Dongjin-bosal were most probably brought together as an all-encompassing protection of Korean Seon Buddhist temples.

And a more specific reason as to why these Eight Devas and Dongjin-bosal were grouped together in a Shinjung Taenghwa is that it has a tangible outcome. In a typical third type of a Shinjung Taenghwa, you’ll find that a naga in the form of Yongwang (The Dragon King) is bigger in size than the neighbouring deities. This size points to the importance of Yongwang being able to control water and prevent fires from happening, which was especially important in a wooden structure like a Korean Daeung-jeon Hall. Interestingly, when Donghwasa Temple was destroyed by fire in 1725, one of the first things the temple did was restore and reproduce the Shinjung Taenghwa.

The fourth type of Shinjung Taenghwa is the kind where you can find up to 104 deities in the mural still with Dongjin-bosal in the middle centre. In this large collection of deities, you’ll see such figures as Daeyejeok Geumgang, who is also known as Mahesvara (an alternate name for Shiva), who is the king of the devas. In Buddhist cosmology, Mahesvara resides in the highest heaven in the form realm. Mahesvara often appears in the Shinjung Taenghwa together with Jeseok, Beomcheon, and Dongjin-bosal. What’s interesting about this is the unexpected rejoining of father (Mahesvara/Shiva) and son (Skanda/Dongjin-bosal).

In addition to the more typical 104 deities in the expanded Shinjung Taenghwa, you’ll also find combinations of 39 deities and as high at 124 deities. The source for the 39 deities comes from the section of “The Wondrous Adornments of World Rulers” from the Avatamsaka Sutra (Kor. Hwaeom-gyeong). However, not all thirty-nine deities from the text make their way into the 124 deities Shinjung Taenghwa. While the massive assembly of deities predominantly comes from the Avatamsaka Sutra, the deities are also from Confucianism, Taoism, and shamanism.

What’s fascinating about these four types of Shinjung Taenghwa is the Korean touch to the diversity found on the canvas. While Dongjin-bosal did appear in several different kinds of paintings paired with different deities from the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) and Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) in Chinese history, it’s not until the diversity, elaborate nature, and wide population that Dongjin-bosal plays a central role in this form of iconography ultimately found in the Korean Buddhist Shinjung Taenghwa. What’s even more fascinating is that there was limited communication between Chinese and Korean Buddhism during the late Joseon Dynasty for political reasons. This allowed Korean Buddhist artists to apply their own imaginations and interpretations to the various deities that included Dongjin-bosal and found a home on the Shinjung Taenghwa.

Shinjung Taenghwas were largely commissioned by both monastics and lay people for various reasons such as earning merits for rebirth, healing, health, longevity, and prosperity. Not surprisingly, with the high demand for Buddhist rituals from the 17th century, we see an explosion of production of ritual manuals and artwork related to these rituals. In fact, individual temples organized various kinds of rituals for local elites and individuals, filling in a gap that was left void by Confucian policies at this time, which helped secure a steady source of income for the temple. This helped free the temple from depending on the support of the central government. And up until 1950, these rituals were performed in front of the Shinjung Taenghwa. However, after the Buddhist Purification Movement in Korea, these rituals were drastically simplified. This, in turn, would lead to a Korean Buddhism that favoured meditation over ritual. In fact, it was the monk Seongcheol (1912-1993) that taught that instead of offering fuller ceremonies to the guardian deities, one could simply recite the Heart Sutra. And it’s from this time period that the systematized rituals for the guardian deities and the Shinjung Taenghwa have been diminished.

The 104 Deities of the Shinjung Taenghwa

| Images of Deity | Deity Name (English) | Deity Name (Korean) | Function and Appearance |

| 1. Daeyejeok-geumgang | 대예적금강 | Mahesvara (an alternate name for Shiva) |

| 2. Cheongjejae-geumgang | 청제재금강 | One of the Eight Diamond Warriors – Eliminates disasters from people’s pasts |

| 3. Byeokdok-geumgang | 벽독금강 | One of the Eight Diamond Warriors – Unknown |

| 4. Hwangsugu-geumgang | 황수구금강 | One of the Eight Diamond Warriors – Wish-fulfiller |

| 5. Baekjeongsu-geumgang | 백정수금강 | One of the Eight Diamond Warriors – Security |

| 6. Jeokseonghwa-geumgang | 적성화금강 | One of the Eight Diamond Warriors – Related to the Buddha |

| 7. Jeongjejae-geumgang | 정제재금강 | One of the Eight Diamond Warriors – Eliminates confusion |

| 8. Jahyeonsin-geumgang | 자현신금강 | One of the Eight Diamond Warriors – Enlightenment |

| 9. Daesinryeok-geumgang | 대신력금강 | One of the Eight Diamond Warriors – Wisdom |

| 10. Gyeongmulgwan-bosal | 경물권보살 | One of the Four Great Bodhisattvas – Awakeness | |

| 11. Jeongeopseak-bosal | 정업색보살 | One of the Four Great Bodhisattvas – Wisdom, good fortune | |

| 12. Jobokae-bosal | 조복애보살 | One of the Four Great Bodhisattvas – Divine spirit | |

| 13. Gunmieo-bosal | 군미어보살 | One of the Four Great Bodhisattvas – Enlightenment | |

| 14. Taegwang-daewang | 태광대왕 | First of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 15. Chogang-daewang | 초강대왕 | Second of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 16. Songje-daewang | 송제대왕 | Third of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 17. Oguan-daewang | 오관대왕 | Fourth of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 18. Yeomra-daewang | 염라대왕 | Fifth of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 19. Byeonseong-daewang | 변성대왕 | Sixth of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 20. Taesan-daewang | 태산대왕 | Seventh of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 21. Pyeongdeung-daewang | 평등대왕 | Eighth of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 22. Dosi-daewang | 도시대왕 | Ninth of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 23. Odojeonryun-daewang | 오도전륜대왕 | Tenth of the Ten Kings of the Underworld |

| 24. Beomcheon | 범천왕 | Brahma |

| 25. Jeseok | 제석천왕 | Indra |

| 26. Damun-cheonwang | 다문천왕 | The Four Heavenly Kings (north) |

| 27. Jiguk-cheonwang | 지국천왕 | The Four Heavenly Kings (east) |

| 28. Jeungjang-cheonwang | 증장천왕 | The Four Heavenly Kings (south) |

| 29. Gwangmok-cheonwang | 광목천왕 | The Four Heavenly Kings (west) |

| 30. Ilgung-cheonja | 일궁천자 | Ilgwang-bosl – Sunlight Bodhisattva, supervises growth of all things |

| 31. Wolgung-cheonja | 월궁천자 | Wolgwang-bosal – Moonlight Bodhisattva, surpervises light |

| 32. Geumgang-miljeok | 금강밀적 | Diamond Warrior | |

| 33. Mahyesura-cheonwang | 마혜수라천왕 | Dacheon | |

| 34. Sanjidaejang | 산지대장 | Rewards good and evil | |

| 35. Daebyeonjae-cheonwang | 대변재천왕 | Music and song, spreads teachings, without obstacles | |

| 36. Daegongdeok-cheonwang | 대공덕천왕 | Great virtue | |

| 37. Witaecheon-shin | 위태천신 | Dongjin-bosal |

| 38. Gyeonnoejishin | 견뇌지신 | Earth Spirit, wealth, cures diseases | |

| 39. Borisusin | 보리수신 | Bodhi Tree Spirit | |

| 40. Gwijamosin | 귀자모신 | Evil Spirit | |

| 41. Marijisin | 마리지신 | Saves from disaster during war (also known as Mariji-bosal) | |

| 42. Sagalra Yongwang | 사갈라용왕 | The Dragon King |

| 43. Yeommara-wang | 염마라왕 | Mara – Rules the Underworld | |

| 44. Jami Daeje | 자미대제 | Leader of the Stars | |

| 45. Tamrang seonggun | 탐랑성군 | Seven Wise Kings | |

| 46. Geomun seonggun | 거문성군 | Seven Wise Kings | |

| 47. Rokjon seonggun | 록존성군 | Seven Wise Kings | |

| 48. Mungok seonggun | 문곡성군 | Seven Wise Kings | |

| 49. Yeomjeong seonggun | 염정성군 | Seven Wise Kings | |

| 50. Mugok seonggun | 무곡성군 | Seven Wise Kings | |

| 51. Pagun seonggun | 파군성군 | Seven Wise Kings | |

| 52. Oebo seonggun | 외보성군 | Big Dipper, 9 stars | |

| 53. Naepil seonggun | 내필성군 | (same as above but different name) | |

| 54. Gaedeok Jingun | 개덕진군 | Chilseong (The Seven Stars) |

| 55. Sagong seonggun | 사공성군 | Related to the stars | |

| 56. Sarok seonggun | 사록성군 | (same as above) | |

| 57. Sukjedae seonggun | 28숙제대성군 | 7 constellations with 4 directions = 28 constellations | |

| 58. Asura | 아수라 | Asura |

| 59. Garura | 가루라 | Garuda |

| 60. Ginnara | 긴나라 | Kimnara |

| 61. Mahuraga | 마후라가 | One of the Eight Devas |

| 62. Hogyedaesin | 호계대신 | Defender of Buddhas followers – has a sword, spear, hat, feather hat at bottom |

| 63. Bokdeokdaesin | 복덕대신 | Spirit of Wealth, love, descendants – has a leopard hat (like helmet) |

| 64. Tojisin | 토지신 | Protector of temple land – has a staff, yellow robe, holds orb in left hand (like a server’s hat) |

| 65. Doryangsin | 도량신 | Protects the Buddhist Three Jewels | |

| 66. Garamsin | 가람신 | Spirit that Protects the Temple |

| 67. Oktaeksin | 옥택신 | Spirit that Protects the Home | |

| 68. Munhosin | 문호신 | Gatekeeper Spirit | |

| 69. Jeongsin | 정신 | Garden Spirit, protector | |

| 70. Jowangsin | 조왕신 | Kitchen Spirit, protector |

| 71. Sansin/Sanshin | 산신 | Mountain Spirit |

| 72. Jeongsin | 정신 | Garden Spirit | |

| 73. Cheuksin | 측신 | Bathroom Spirit, cleans up unclean things | |

| 74. Daeaesin | 대애신 | Spirit that Nourishes People with Grains | |

| 75. Susin | 수신 | Water Spirit, ravines | |

| 76. Hwasin | 화신 | Fire Spirit, eliminates darkness | |

| 77. Geumsin | 금신 | Gold/Jewel Spirit | |

| 78. Moksin | 목신 | Tree Spirit, king of the forests | |

| 79. Tosin | 토신 | Relieves suffering and misfortune | |

| 80. Bangsin | 방신 | Spirit that Removes Temptation | |

| 81. Togongsin | 토공신 | Spirit that Relieves Suffering | |

| 82. Bangwisin | 방위신 | Spirit of the Seasons | |

| 83. Sijiksin | 시직신 | Gave the world light and lifted it from darkness | |

| 84. Gwangyasin | 광야신 | Spirit of Harvests/Fields | |

| 85. Haesin | 해신 | Sea Spirit | |

| 86. Hasin | 하신 | River Spirit | |

| 87. Gangsin | 강신 | Large River Spirit | |

| 88. Dorosin | 도로신 | Protects people and guides them on the right path | |

| 89. Seongsin | 성신 | Defender of the nature of the heart | |

| 90. Chohwoesin | 초훼신 | Cloud Spirit | |

| 91. Gasin | 가신 | Five Valleys Spirit | |

| 92. Pungsin | 풍신 | Wind Spirit | |

| 93. Usin | 우신 | Spirit of Grief, follows people’s karma | |

| 94. Jusin | 주신 | Day Spirit | |

| 95. Yasin | 야신 | Night Spirit | |

| 96. Sinjungsin | 신중신 | Cycle of Life Spirit | |

| 97. Jokhaengsin | 족행신 | Freedom of Movement Spirit | |

| 98. Myeongsin | 명신 | Lifespan Spirit | |

| 99. Roksin | 록신 | Honour Spirit | |

| 100. Seonsin | 선신 | Records People Doing Good Deeds Spirit | |

| 101. Aksin | 악신 | Records People Doing Evil Deeds Spirit | |

| 102. Beolbyeongsin | 벌병신 | Gives illness to people doing bad deeds | |

| 103. Duchanggochalsin | 두창고찰신 | Presides over epidemics | |

| 104. Iui 3-jae 5-aengsin | 이의3재5행신 | Presides over everything in the world/harmony of heaven and earth |

Conclusion

The rise in importance of Dongjin-bosal, and his inclusion in the Shinjung Taenghwa, is a long tradition that first started in North India, continued in China, and resulted in his landing in Goryeo Dynasty Korea. All of these changes of the long-standing popularity of Skanda (Dongjin-bosal) are rooted in ancient Indian mythology. Some of these early aspects found a home in the Sino iconography of Skanda (Weituo) in China. Afterwards, these numerous changes are then translated in various forms and homes for Skanda (Dongjin-bosal) in Korea. And it’s through this prolonged period of time and cross-cultural pollination that we arrive at the symbolic meaning and value of this deity in the Korean Shinjung Taenghwa. Starting as a minor deity in cultish beliefs in rural pre-modern India, we arrive at a centrality to Dongjin-bosal as a protector of the Three Jewels of Korean Buddhism inside Korean temple shrine halls.