Tap – The Korean Pagoda: 탑

Introduction

One of the most noticeable, and important features of a Korean Buddhist temple is a pagoda. The history of the pagoda in Korea is as old as Buddhism in Korea. And while a pagoda’s design is both beautiful and elegant, it’s also packed with symbolic meaning that may not always be all that evident. So when did the pagoda first appear in Korea? Why is the pagoda situated at a Korean Buddhist temple? What do they look like? And why are they designed the way they are?

History

Originally, in India, Buddhist temples were centred around stupas. The word stupa means heap in Sanskrit because these pagodas were in fact nothing more than mounds of earth. In Sanskrit, the original name for these structures is “soldopa.” Over time, this changed through its migration eastwards to “dopa,” “tupa,” and “tapa.” The word “tapa” is just one of the numerous ways in which the Chinese translated the original word. Until eventually it became “tap” when the word arrived on the Korean peninsula.

The first stupas that were ever created, as the original meaning of the name indicates, were nothing more than mounds of raised earth with the base of the mounds having a brick or stone border. As time went on, and as the Buddhist tradition evolved and changed, a stupa was topped with a stone peak.

As the Buddhist tradition evolved, the stupa eventually would be topped with a pedestal with a stone peak. Historically, a stupa was created to house the remains of the Buddha. Presently, and historically throughout Korean history, in the absence of the Buddha’s remains, they would house important artifacts and treasures related to Buddhism.

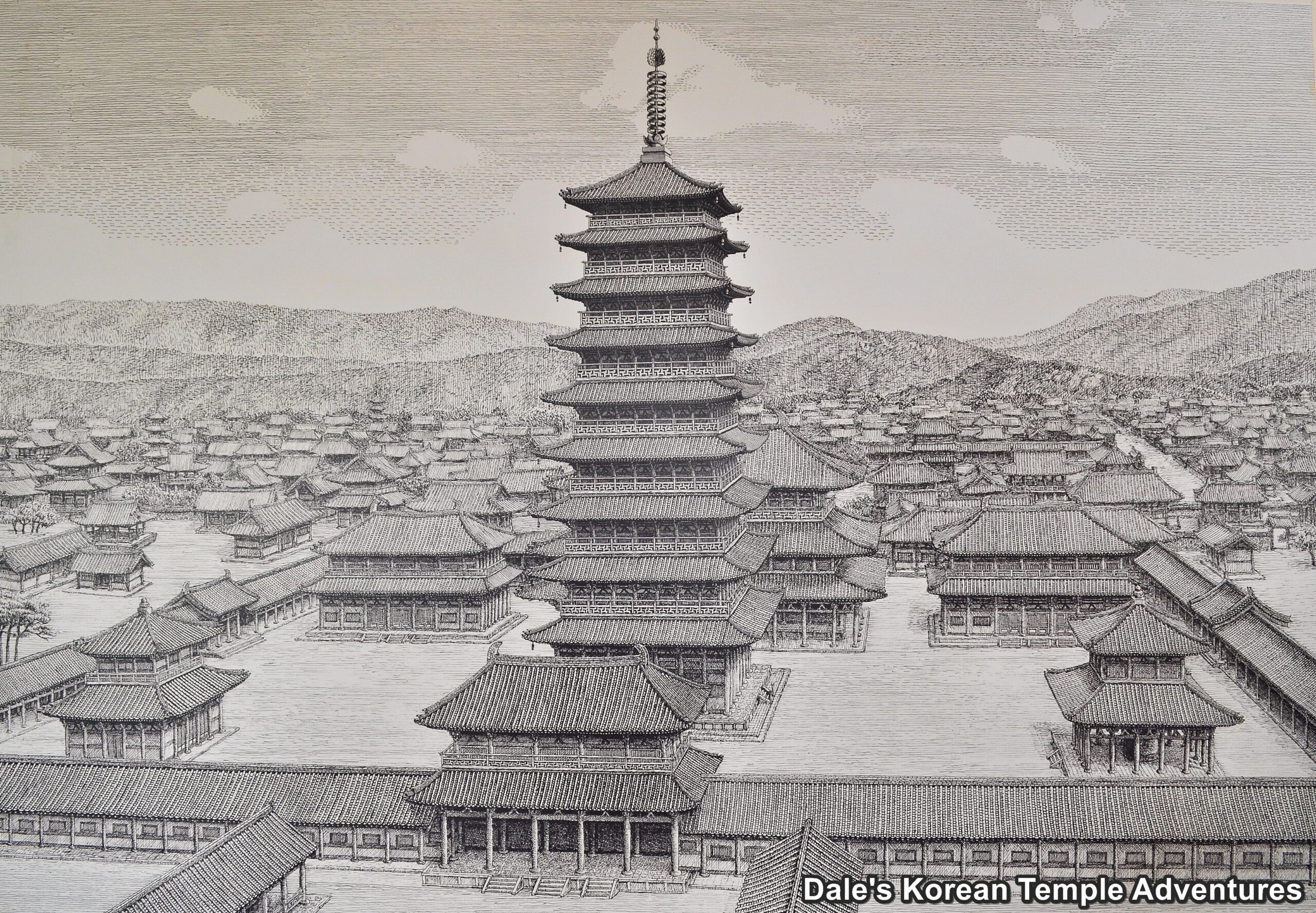

Like all things in Asian Buddhism, its traditions and teachings migrated eastwards from India and onto China, where it forked in several directions including the Korean peninsula. As it did this, stupas disappeared, and the Chinese wooden pagoda gained in popularity. This popular form of the pagoda would find a home on the Korean peninsula. In time, however, the wooden pagoda would be replaced by stone pagodas during the Three Kingdoms period in Korean history. These massive wooden pagodas were popular in the Goguryeo Kingdom; however, in the Silla and Baekje Kingdoms, the wooden pagoda was less popular. Unfortunately, there are no remaining wooden pagodas in Korea; instead, all that now exists of these wooden creations are their remains.

A: Goguryeo Kingdom Pagodas:

Goguryeo Kingdom (37 B.C. – 668 A.D.) pagodas were typically octagonal in shape and they were made from wood. This design was then popularized later during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). A great example of this design can be seen at Woljeongsa Temple. This type of octagonal design would continue to be popular until the early Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). This octagonal design was a sign of sacredness.

B: Baekje Kingdom Pagodas:

Baekje Kingdom (18 B.C. – 660 A.D.) pagodas followed the more conventional ideal of wooden pagodas. The eaves of these pagodas were spread out broadly and thinly with a slightly upturned edge to them. These pagodas had a small degree of tapering as they gradually moved upwards. A great stone manifestation of what these wooden pagodas looked like can be seen at Mireuksa-ji Temple Site.

C: Silla Kingdom Pagodas:

Originally, the Silla Kingdom (57 B.C. – 935 A.D.) used wood to build pagodas. The best known example could be found at Hwangnyongsa-ji Temple Site in Gyeongju. In time, these wooden pagodas were then made by chiseled stone bricks like at the neighbouring Bunhwangsa Temple also in Gyeongju. The reason that the brick design was popular during the Silla Kingdom is that it was difficult to hoist large pieces of stone into a tall pagoda structure. Eventually, and with the advancement in technology, these stone bricks turned into partial or solid stone pagodas that we see today.

It was also during the Silla Kingdom that pagodas were built in pairs. Twin pagodas were seen as having a mystical power that would help defend the nation. The twin pagodas were also believed to have the power to summon mystical forces which were believed to be separate and independent from a place to solely worship the Buddha’s remains. A great example of these twin pagodas can be seen at the Gameunsa-ji Temple Site in eastern Gyeongju.

D: Unified Silla Pagodas:

The cultural peak of the Unified Silla Dynasty (668-935 A.D.) took place during the mid 8th century. This also resulted in the peak of artistry in Buddhism, as well. Great examples of this artistic achievement can be found at Bulguksa Temple in the form of Dabo-tap Pagoda and Seokga-tap Pagoda in Gyeongju. These two pagodas are believed to be what perfect pagodas are supposed to be.

Stylistically, pagodas started to change at this time, as well. The door on the face of the pagoda was now added. Instead of a pagoda once being an inescapable tomb, they were now viewed as a place where the living could come and go freely. Pagodas also became far more elaborate in design. The Eight Dharma Protectors were added to the base of a pagoda, and Geumgang-yeoksa were added to the first tier of the body of the pagoda. Because divine beings and deities played an increasingly greater role in Buddhist rites at this time, Unified Silla pagodas also started to be decorated with them.

In time, however, the centrality of the pagoda at Korean temples would loosen until eventually it would disappear from some temple grounds. Perhaps the greatest example of this can be found at Songgwangsa Temple in Suncheon, Jeollanam-do. However, with that being said, pagodas are still an integral part of Korean Buddhist temples both new and old.

Pagoda Design

While the design of the Korean pagoda has varied over time, the structural components that make the Korean pagoda what it is have remained, fundamentally, the same. They are: the base, the body, and the finial.

A: The Pagoda Base:

Of the three components of a Korean Buddhist pagoda, the base is situated on the lowest part of the structure. Usually, the base is four sided, and it’s decorated in a variety of Buddhist imagery. Some of the more common images that appear on the base of the pagoda are reliefs of the Twelve Zodiac Generals, the Eight Dharma Protectors and/or the Sacheonwang (The Four Heavenly Kings).

The Twelve Zodiac Generals are the exact same ones that are known, in the West, as the Chinese zodiac signs. They are: the rat, the ox, the tiger, the rabbit, the dragon, the snake, the horse, the sheep, the monkey, the rooster, the dog, and the pig. They most often appear as reliefs on the four sides of the pagoda in triplets. The twelve are traditionally depicted with human bodies dressed in armour or robes. And their heads are one of the twelve Chinese zodiac signs. The reason that they adorn the base of a Korean Buddhist pagoda is that they are carrying out The Twelve Great Vows of Yaksayeorae-bul (The Buddha of Medicine, and the Buddha of the Eastern Paradise). As such, they promised to protect the Dharma, which is manifested around the base of the stone pagoda.

As for the Eight Dharma Protectors, they too can appear around the base of Korean Buddhist pagoda. These Eight Dharma Protectors were once seen as being evil, but they were later converted by Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha). These Eight Dharma Protectors are: 1. Deva, 2. Naga, 3. Yaksha, 4. Gandarva, 5. Asura, 6. Garuda, 7. Kinnara, 8. Mahoraga.

The first of these are Deva. Deva are thought to be celestial beings that can control part of nature like fire, wind, and/or air. The second of the eight are Naga. Naga generally take the form of a great cobra. They have the power to transform into a humans. The third are Yaksha. Yaksha are beings with lions on their heads and a rope around their waist. They are ugly, cruel and ghost-like creatures that were believed to fly around at night to torment humans. The fourth of the eight are Gandarva. Gandarva have a sword in their right hand and a small bottle of perfume in their left. They live off the fragrance of their perfume.

The fifth of the eight are Asura. Asura have a bird-like head with three faces and six arms. Sometimes they appear with a monster mask in the centre of their stomachs. This monster mask, or Gwimyeon, in Korean, symbolizes evil being suppressed. The sixth of the Eight Dharma Protectors is the Garuda. Garuda have bird-like wings on the outer edges of their ears. In Indian myth, they are the king of birds. The seventh of the eight are Kinnara. Kinnara have long hair, and they’re holding a trident in their left hands. They are depicted as having a human head and a bird’s body. They are known as heavenly musicians. In some renderings, they are sometimes depicted as playing drums or the flute. The eight, and final Dharma protector, is the Mahoraga. Mahoraga hold a sword in their right hand, while their left hand’s palm is slightly crooked. Mahoraga are meant to symbolize the snake spirit. It has a human body and a snake’s head. A Mahoragas slithers on the ground.

The set of reliefs that can also appear on the base of a Korean Buddhist pagoda are the Sacheonwang, or The Four Heavenly Kings, in English. Yes, these are the very same kings that appear inside the Cheonwangmun Gate at the entry of a temple. The four are easy to recognize. Damun Cheonwang is the King of the North, and he’s holding a pagoda in his hand. Jeungjang Cheonwang, on the other hand, is the King of the South, and he holds a sword in his hands. Another of the four is Gwangmok Cheonwang who is the King of the West, and he holds a dragon and/or jewel in his hands. And the final one is Jigook Cheonwang who is the King of the East, and he holds a lute in his hands.

Anyone of the three groups can appear around the base of a Korean Buddhist pagoda. And it’s always interesting to figure out which of the three is actually appearing around the base of the pagoda. It’s like being a Buddhist iconography detective.

B: The Pagoda Body:

The body of the pagoda is built, rather logically, upon its base. Each story/tier of a pagoda’s body consists of a body stone and a roof stone. Much like the base of the pagoda, the body can also be adorned with various images like Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, the Geumgang-yeoksa (Vajra Warriors) or even the Four Heavenly Kings.

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas can appear on the pagoda’s body as a relief because it’s believed that they have universal and unlimited powers. And the Four Heavenly Kings appear around the body of a Korean pagoda because they have sworn to protect the Dharma.

As for Geumgang-yeoksa, which are also known as Benevolent Kings, they originated in India as a Vajrapani deity. The name Vajrapani, or Vajra for short, means enormous physical power. As a result, they are typically identified with Indra, who is a thunderbolt throwing Vedic deity. These Vajra, or Geumgang-yeoksa, are traditionally shown in pairs on either side of an entryway. These deities don’t hold anything in their hands; instead, their hands are clenched in fists of rage. This gesture differentiates them from the Four Heavenly Kings. Great examples of this can be found at Bunhwangsa Temple in Gyeongju.

Two additional images that can appear around the body of a Korean Buddhist pagoda can be a padlock-like image. This relief is meant to not only protect the contents of the pagoda symbolically, but it’s also meant to suggest that the body is a kind of dwelling. And the other image that can adorn the body of pagodas are floral designs.

Another aspect of a pagoda’s body are the varying number of stories that make up the height of a Korean Buddhist pagoda. Even the amount of stories have a symbolic meaning attached to them.

Most pagodas in Korea have an odd amount of stories whether it be three, five, seven, nine, or eleven. Hardly ever will you find a Korean Buddhist pagoda have an even amount of stories. Oddly numbered pagodas come from the East Asian worldview of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements Theory, so it’s not necessarily grounded in Buddhism. Traditionally, East Asian people were influenced by the idea that heaven and earth, particularly humans, were interconnected. An example of this are natural disasters. So those that could harness the power of natural laws were believed to be equal with heaven and earth, and they could wield cosmic laws and principles. More specifically, Koreans attempted to harness this sort of power in their daily lives. One way they attempted to do this was through numbers, which were believed to correspond to cosmic principles.

Specifically, the number of stories in a pagoda are related to the idea of Heaven and Earth. These numbers start with the number one and end with the number ten. One, three, five, seven, and nine are Yang, which is meant to represent hot, light, and male. Nine, in the set, is a culmination of the Yang principle. On the other hand, even numbers like two, four, six, eight, and ten are Yin, and they are meant to represent cold, dark, and female. And ten is the culminating number of the Yin principle. Furthermore, Yang (odd numbers) is considered to be above, in front of, and/or higher in human affairs. As a result, Yang is associated with the noble, respect, auspiciousness, and good fortune. Conversely, Yin (even numbers) are seen as being below, behind, and/or beneath. In human affairs, Yin is connected to human affairs that are thought to be lowly, debased, inauspicious, and/or calamitous. With all this symbolism in mind, it’s obvious as to why the designers of Korean pagodas would want the stories of the pagoda to be even in number. This way, a pagoda can act as a physical manifestation of those things that are seen as good and favourable.

If we specifically look at each of the odd numbers, we find that the number three embodies the idea of completeness. The number three is also considered to be an auspicious number. The number five, on the other hand, is the midway point between one and ten; as a result, the number five is meant to symbolize the heavenly position. The number five is symbolic of the five elemental forces of fire, water, earth, metal, and wind. The number seven symbolizes heaven, earth, and humanity. It’s also used to represent Chilseong (The Seven Star, also known as the Big Dipper), who is a prevalent figure in Korean Buddhism and shamanism. Finally, the number nine is yang at its fullest. It’s also the number behind the Nine Celestial Bodies. Nine is also similar in sound with the character meaning “a long time,” or “long lasting.” As a result, nine is a symbol of nobility and good fortune.

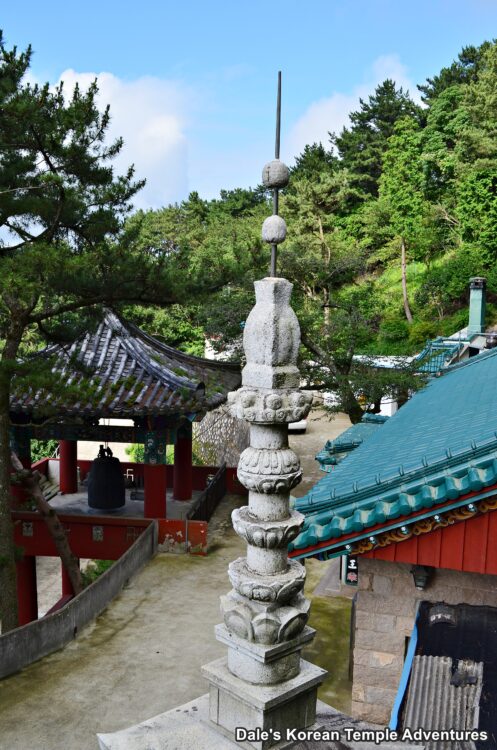

C: The Pagoda Finial:

The final component to a Korean Buddhist pagoda is the finial which sits atop the pagoda. The finial has its own base, upon which rests a series of extremely ornate ornamental objects that are stacked one on top of the other. In Korean, the finial is known as the “Sangnyun,” which means “Sign of Wheels,” in English. This design feature of a Korean Buddhist temple is in reference to the Nine Circular Wheels or Sacred Wheels in Buddhism. Historically, if a pagoda’s finial had nine wheels, it was supposed to contain the partial remains of Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha).

In total, there are eight components to a Korean Buddhist pagoda finial. Each of the eight components are stacked one on top of the other in a vertical shaft. These eight, in order from the base, are 1. the base, 2. the inverted bowl, 3. the upturned lotus, 4. the sacred wheels, 5. the sacred canopy, 6. the water flame, 7. the dragon wheel, and 8. the sacred pearl.

The first of the eight components of the finial is the Base. In Korean, this is known as the “noban.” And it’s a box-like structure. The base is also known as the “dew receiver.” The second part of the finial is the Inverted Bowl. In Korean, this is known as the “bokbal.” It has been argued that this design is a carry-over from the original stupa burial mounds in India. The third component is the Upturned Lotus. In Korean, this Upturned Lotus is known as an “Anghwa.” This part of the finial literally looks like an upturned flower. The fourth component of the finial is the Sacred Wheel. In Korean, this is called a “boryun.” This is the central part of the finial.

The fifth part of the finial is the Sacred Canopy. In Korean, it’s known as the “bogae.” This part is in reference to the gem-decorated canopy above a temple shrine hall’s main altar and the statues that adorn it. It’s also additionally meant to represent the ultimate state of nirvana. The sixth component is called the Water Flame, which is known as the “suyeon,” in Korean. The reason that this appears on a finial is that temple’s feared fire could potentially devastate its shrine halls, so they balanced the imagery of fire with water. The seventh component is known as the Dragon Wheel/Vehicle. The shape of this part is oval. And the eighth, and final component to a Korean Buddhist pagoda finial, is the Sacred Pearl. In Korean, this part is known as either a “boju” or a “yongcha.” The word “boju” means a sacred pearl or precious gem. This part of the finial is the uppermost part of the finial. The “boju” shines on all objects in the universe, and it eliminates all forms of disease and ailments.

Conclusion

In total, there are two hundred and three pagodas that are protected as cultural properties by the Korean government. Of these two hundred and three, there are thirty-one pagodas that are Korean National Treasures. There are an additional one hundred and eighty-nine that are Korean Treasures. One pagoda that’s a National Registered Cultural Heritage. Three that are Tangible Cultural Heritages. And six pagodas that are Cultural Properties Materials.

Of the two hundred and three pagodas, the majority, one hundred and twenty-seven, are three-story pagodas. The next most common pagoda is the five-story pagoda. In total, there are forty-six of them. The next most common pagoda structure has seven stories. In total, there are eleven of them. The next most common are the nine-story pagodas. In total, there are four of them. And there is only one pagoda with eleven stories and one pagoda with thirteen stories that are protected by the Korean government. So in total, there are one hundred and ninety pagodas of the two hundred and three pagodas that are odd in number. That leaves just eight pagodas that are even in number. There are two pagodas that are recognized by the Korean government that have two stories; two with six stories; one with eight stories; and three with ten stories. In addition, because of circumstances, there are five with an unknown amount of stories because of damage, the passage of time, and a lack of documentation.

The most famous pagodas in Korea, but certainly not limited to, are the Ten-Story Stone Pagoda at Wongaksa Temple Site (N.T. #2); Stone Pagoda at Mireuksa Temple Site (N.T. #11); Dabo-tap Pagoda at Bulguksa Temple (N.T. #20); Seokga-tap Pagoda at Bulguksa Temple (N.T. #21); Stone Brick Pagoda of Bunhwangsa Temple (N.T. #30); Four Lion Three-Story Stone Pagoda of Hwaeomsa Temple (N.T. #35); Octagonal Nine-Story Stone Pagoda of Woljeongsa Temple (N.T. #48-1); and the East and West Three-Story Stone Pagodas at the Gameunsa-ji Temple Site (N.T. #112).

As you can see, Korean Buddhist pagodas not only have a long history accented by various designs, but the very designs themselves are filled with symbolic meaning. Some of that meaning is rather obvious, while a lot of the meaning is a bit more obscure. So the next time you’re are a Korean Buddhist temple or hermitage, have a look for the pagoda and all the meaning that’s potentially packed into its design.