Colonial Korea – Beopjusa Temple

Temple History

Beopjusa Temple is situated in Songnisan National Park to the north-east of Boeun-gun, Chungcheongbuk-do. Beopjusa Temple means, “Dharma Residence Temple” in English. According to the Dongguk-yeoji-seungnam, or the “Survey of the Geography of Korea” in English, Beopjusa Temple was first founded in 553 A.D. by the monk Uisin. After traveling to India to learn more about Buddhism, Uisan returned to the Korean Peninsula with Indian Buddhist scriptures. Carrying these scriptures on a white donkey, he housed these texts at the temple he was to build: Beopjusa Temple.

According to historical documents, the famed monk Jinpyo (8th century) returned to the Mt. Songnisan area and marked a location where it was an auspicious place to grow plants. Afterwards, he traveled on towards Mt. Geumgangsan (now apart of North Korea). There, he founded a temple and stayed at Baryeonsusa Temple. While staying there, he received disciples that had traveled all the way from Mt. Songnisan like the monks Yeongsim, Yungjong, and Bulta. They came to receive the Dharma from Jinpyo. During their meeting with Jinpyo, Jinpyo was to tell his disciples, “I’ve marked the area where auspicious plants grow on Mt. Songnisan. Build a temple there to save the world according to the doctrines of the Dharma and disseminate them among the future generation.” Obeying Jinpyo, the group of monks returned to Mt. Songnisan and found the place that Jinpyo had marked. There, they built a temple which they were to name Gilsangsa Temple. By 1478, and as recorded in the Dongmunseon (Anthology of Eastern Literature), the temple name was recorded as Songnisa Temple. Later, it would regain its former name of Beopjusa Temple.

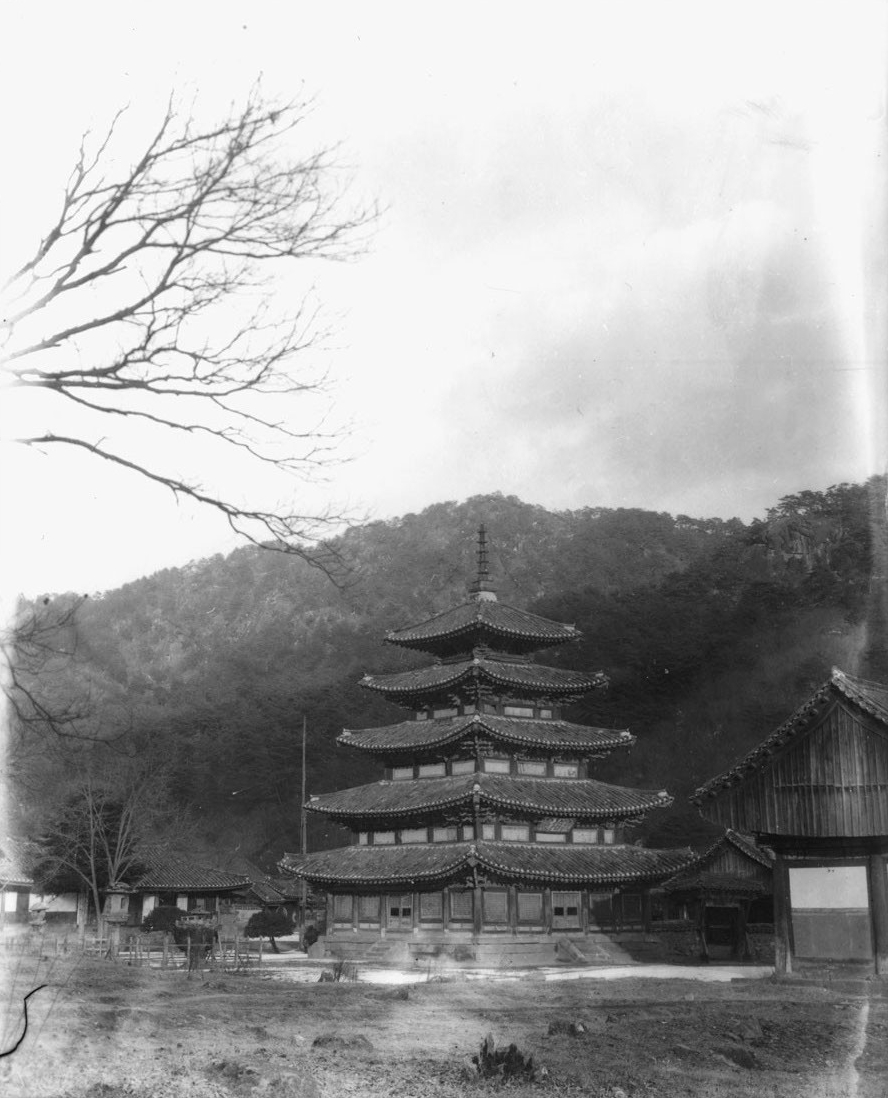

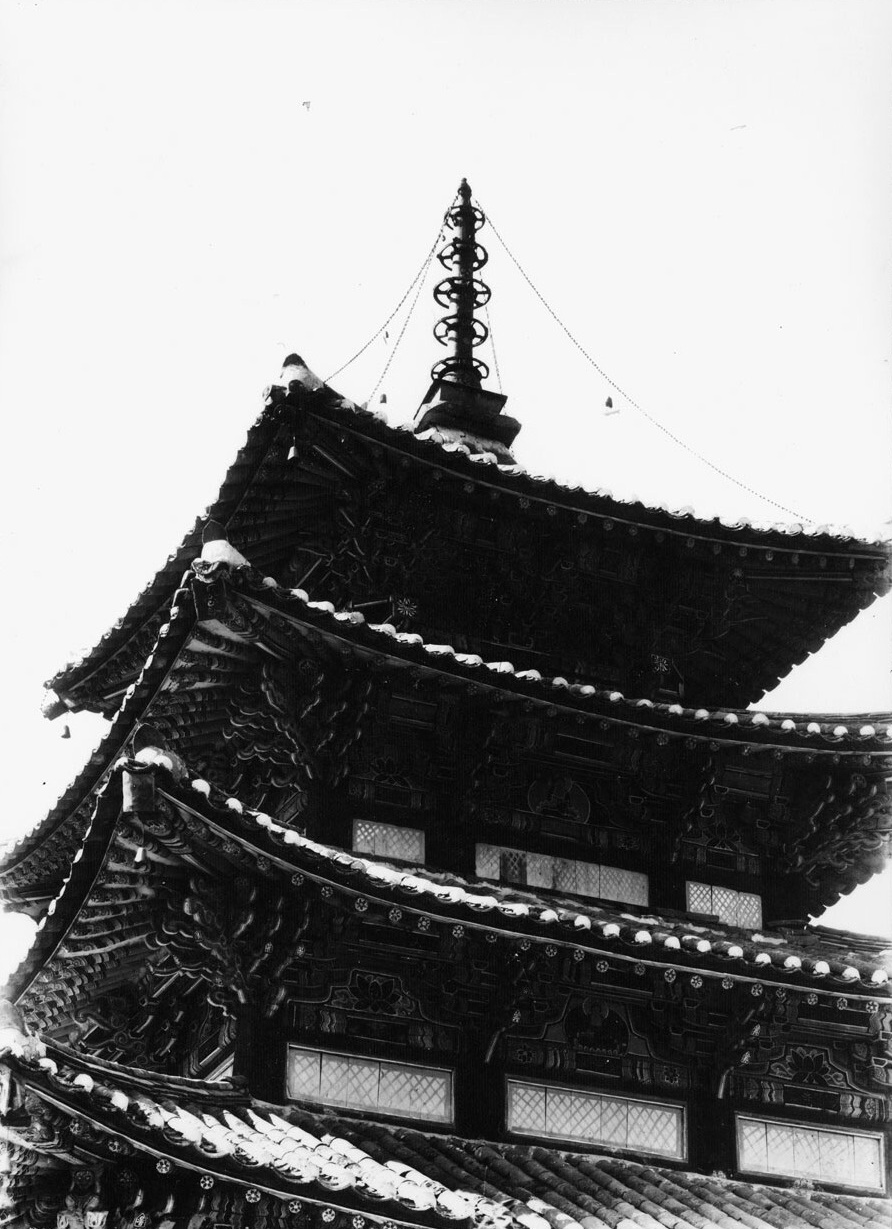

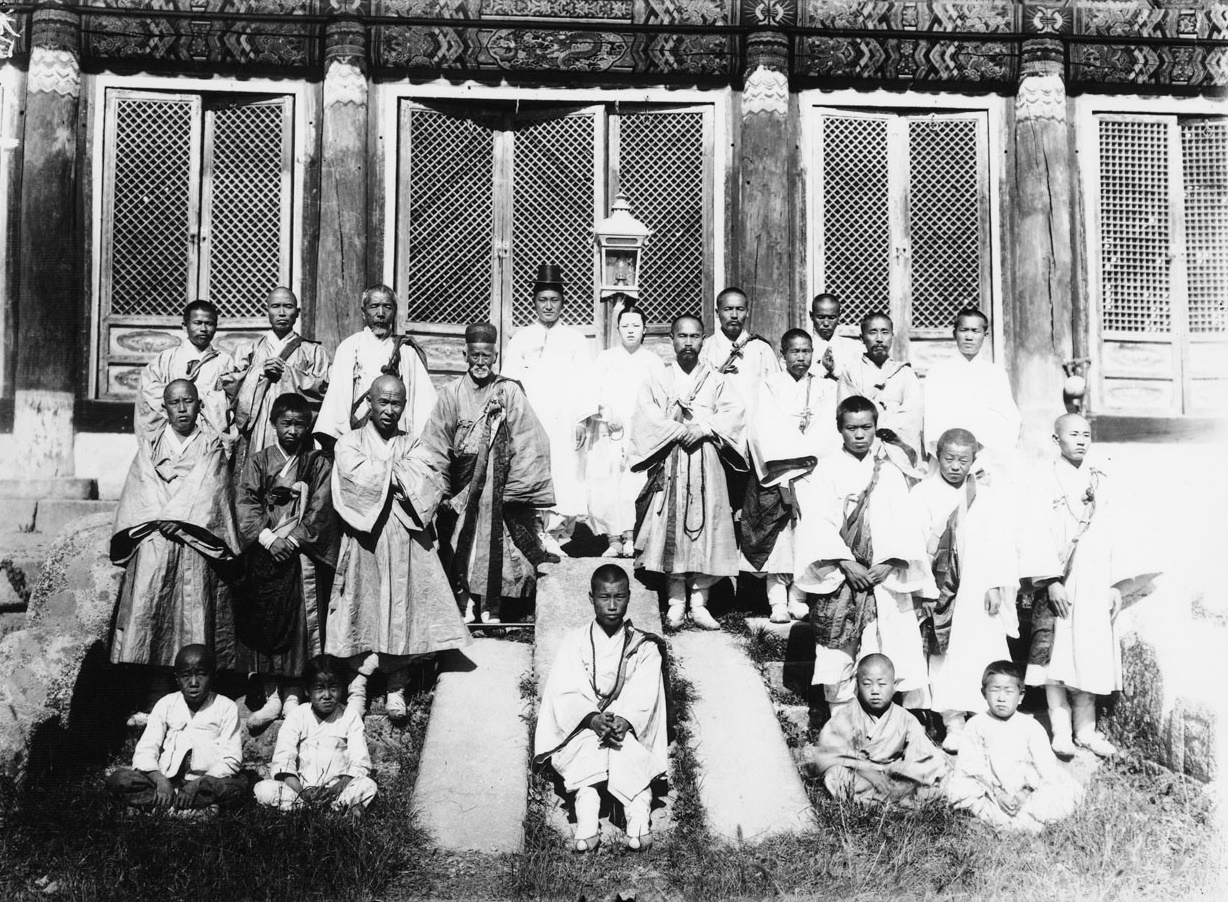

At its peak, the temple was home to three thousand monks, some sixty buildings and seventy hermitages. At one point during the early 1100’s, over 30,000 monks gathered at Beopjusa Temple to pray for the dying Uicheon-guksa (1055-1101). Like countless other structures in Korea at that time, Beopjusa Temple was utterly destroyed by the invading Japanese during the Imjin War (1592-98). Three decades later, Beopjusa Temple was rebuilt in 1624. And several of the buildings that currently reside at the temple date back to this year like the famed five-story wooden pagoda, the Palsang-jeon Hall.

During the waning years of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), and in 1851, Prime Minister Gwon Don-in state sponsored a national renovation and restoration of Beopjusa Temple. This project was furthered by King Gojong (King of Korea reign 1863-97; Emperor of Korea reign 1897-1907) in 1906. Then, in 1964, president Park Chung Hee (1917-79) financed the construction of a twenty-nine metre tall cement standing statue of Mireuk-bul (The Future Buddha). This was followed-up by the efforts of Master Taejeon Geumho in 1974, with the help of government funding, of an all-out repair and restoration of most of the buildings at Beopjusa Temple. And in the early 1970’s, the temple had been chosen as a setting for the Bruce Lee movie, “Game of Death.” In fact, the Palsang-jeon Hall had been chosen as a filming location because the five floors of the pagoda were meant to represent the five different martial arts. However, before the film could be completed, Bruce Lee tragically died and Beopjusa Temple was edited out of the final movie. In 1988, the massive bronze statue of Mireuk-bul (The Future Buddha) that stands at thirty-three metres in height replaced the twenty year old cement statue of the same Buddha at the temple.

In total, the temple is home to an amazing three National Treasure, thirteen Korean Treasures, one historic site, and one scenic site.

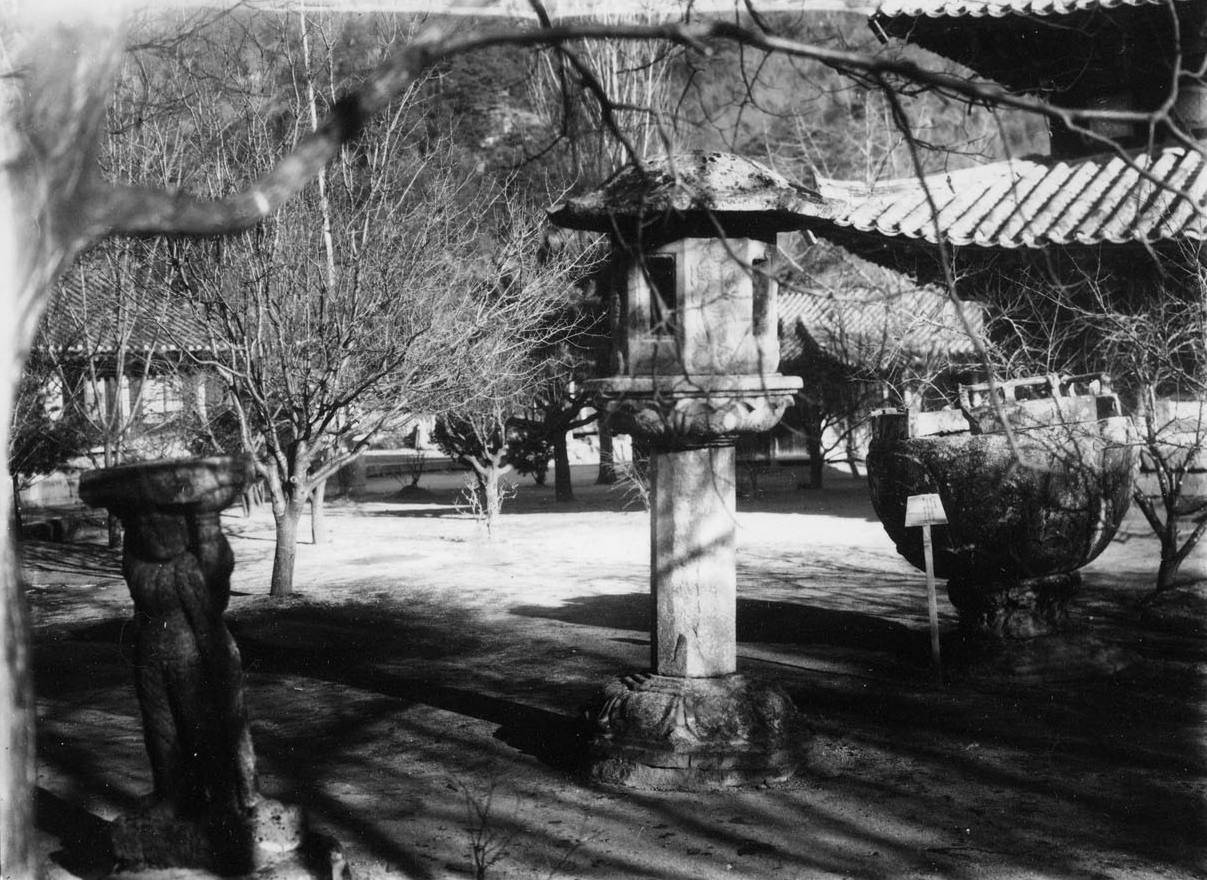

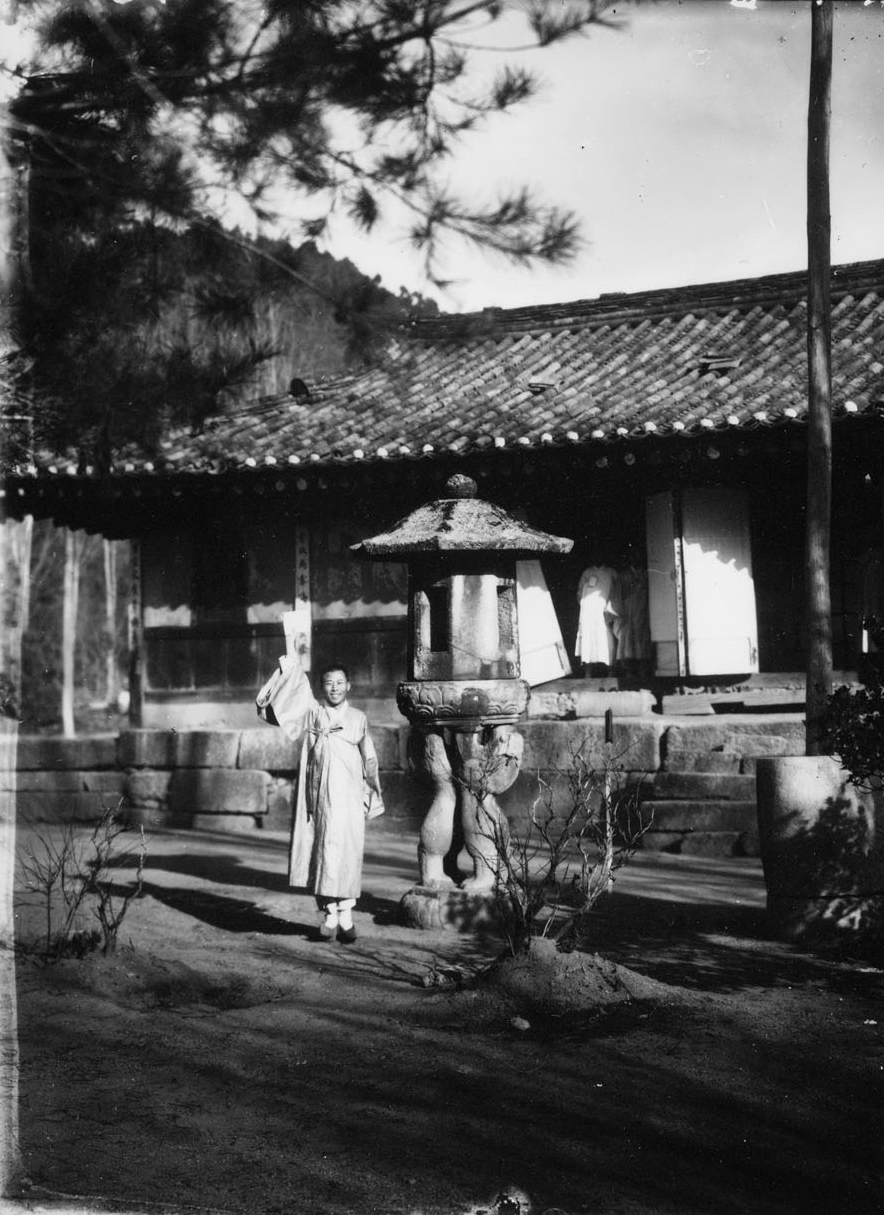

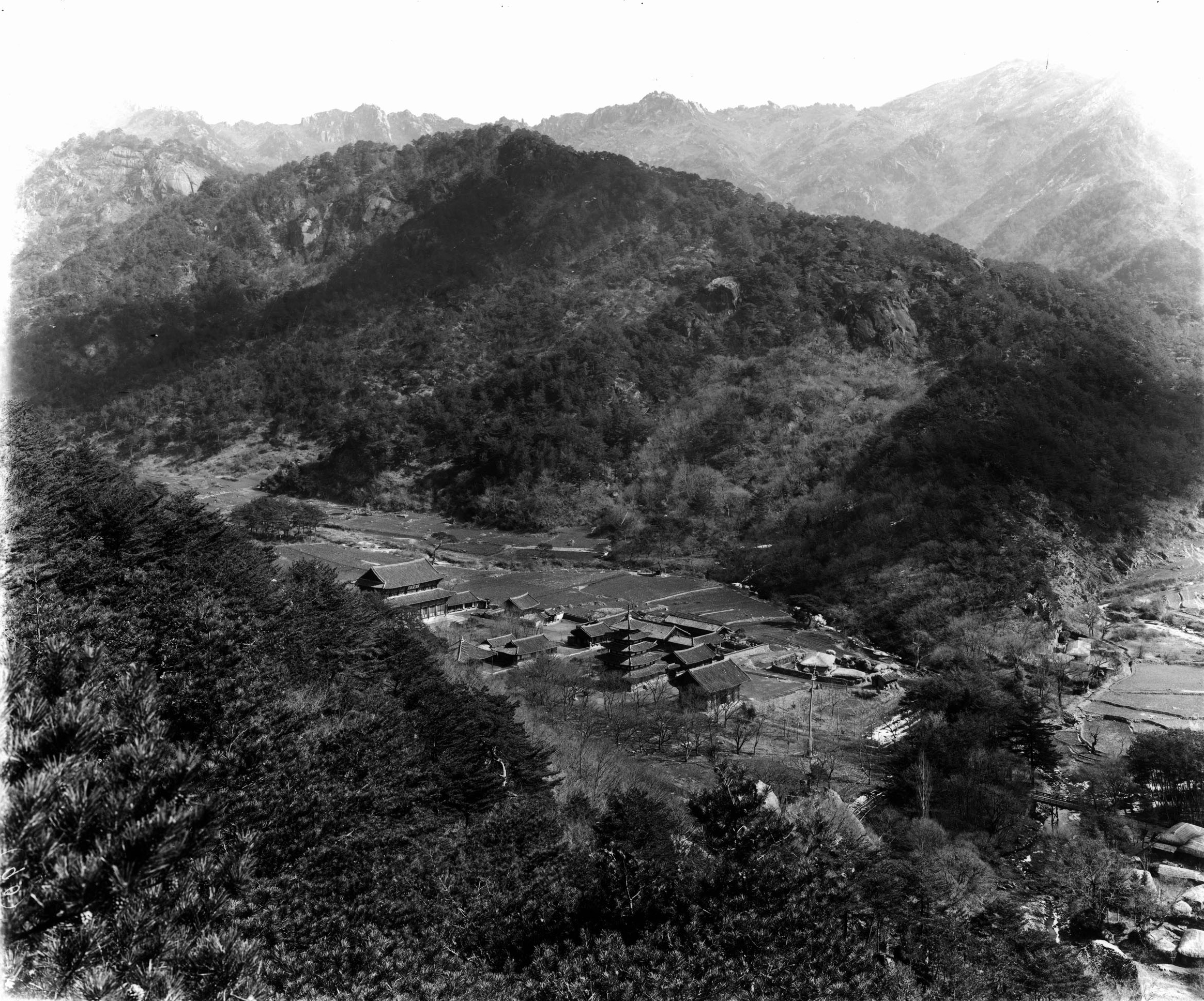

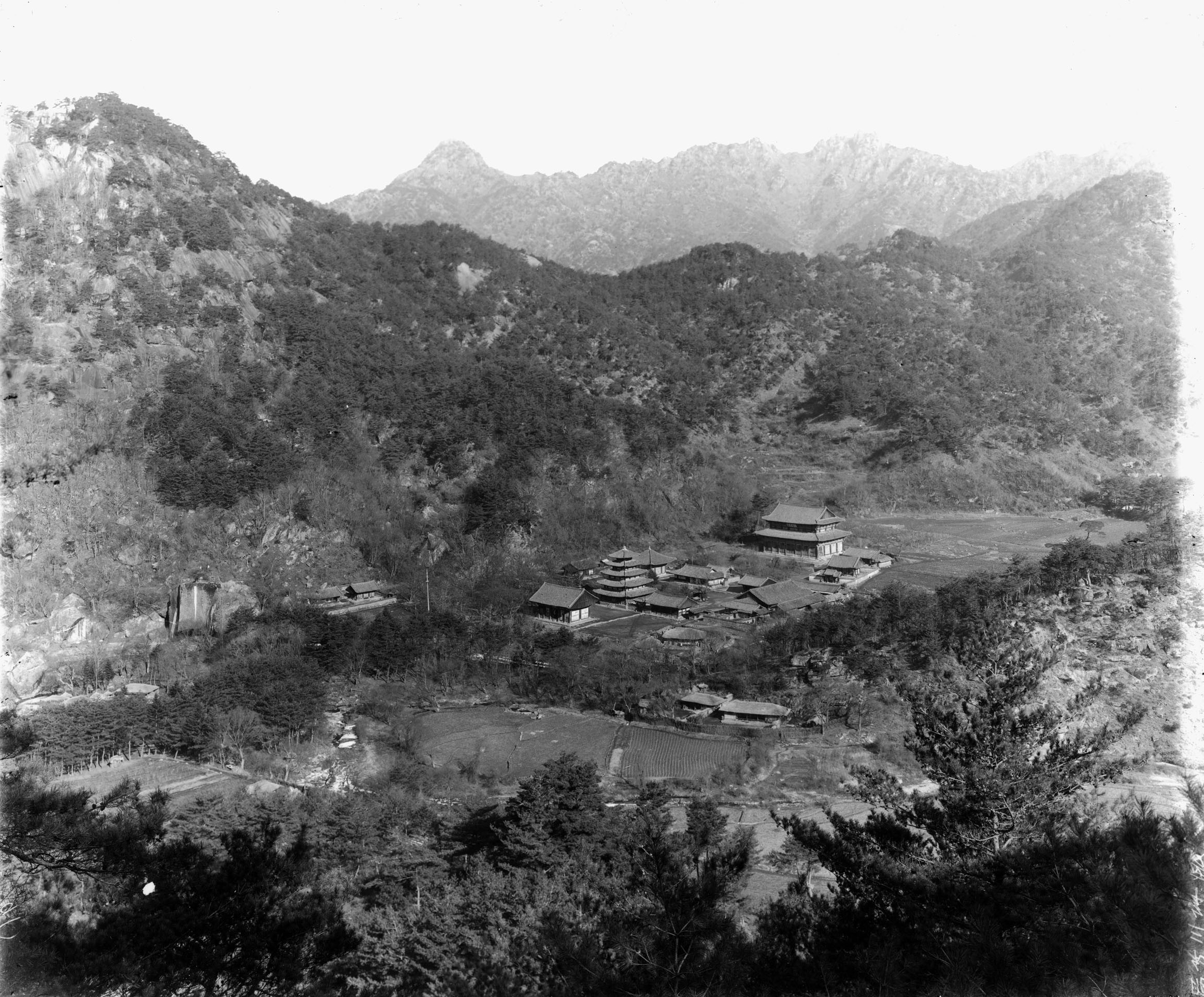

Colonial Era Photography

It should be noted that one of the reasons that the Japanese took so many pictures of Korean Buddhist temples during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945) was to provide images for tourist photos and illustrations in guidebooks, postcards, and photo albums for Japanese consumption. They would then juxtapose these images of “old Korea” with “now” images of Korea. The former category identified the old Korea with old customs and traditions through grainy black-and-white photos.

These “old Korea” images were then contrasted with “new” Korea images featuring recently constructed modern colonial structures built by the Japanese. This was especially true for archaeological or temple work that contrasted the dilapidated former structures with the recently renovated or rebuilt Japanese efforts on the old Korean structures contrasting Japan’s efforts with the way that Korea had long neglected their most treasured of structures and/or sites.

This visual methodology was a tried and true method of contrasting the old (bad) with the new (good). All of this was done to show the success of Japan’s “civilizing mission” on the rest of the world and especially on the Korean Peninsula. Furthering this visual propaganda was supplemental material that explained the inseparable nature found between Koreans and the Japanese from the beginning of time.

To further reinforce this point, the archaeological “rediscovery” of Japan’s antiquity in the form of excavated sites of beautifully restored Silla temples and tombs found in Japanese photography was the most tangible evidence for the supposed common ancestry both racially and culturally. As such, the colonial travel industry played a large part in promoting this “nostalgic” image of Korea as a lost and poor country, whose shared cultural and ethnic past was being restored to prominence once more through the superior Japanese and their “enlightened” government. And Beopjusa Temple played a part in the propagation of this propaganda, especially since it played such a prominent role in Korean Buddhist history and culture. Here are a collection of Colonial era pictures of Beopjusa Temple through the years.

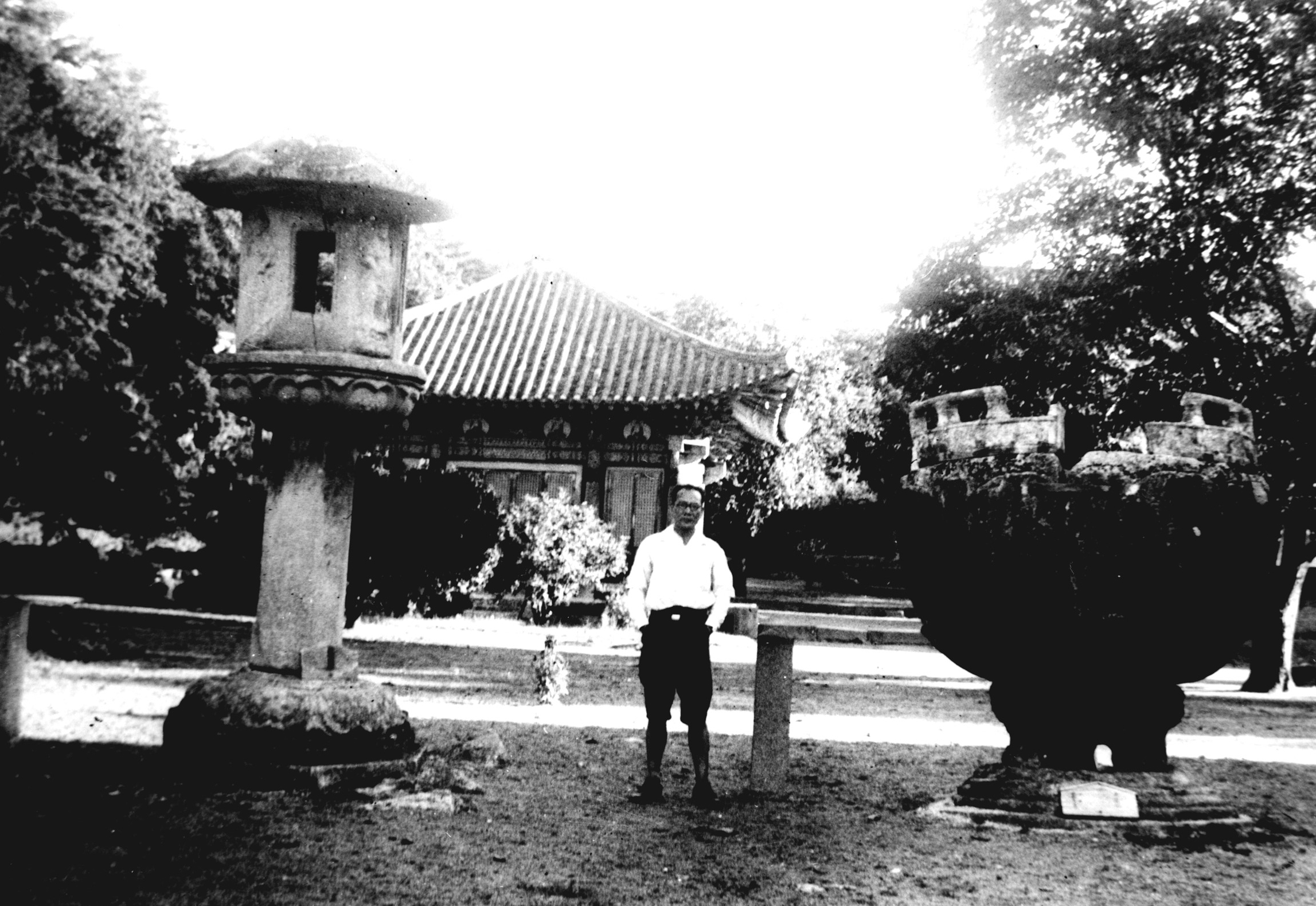

Pictures of Colonial Era Beopjusa Temple

1910

Pictures of Colonial Era Beopjusa Temple

1921

Pictures of Colonial Era Beopjusa Temple

1928

Pictures of Colonial Era Beopjusa Temple

1929

Pictures of Colonial Era Beopjusa Temple

Specific Dates Unknown (1909-1945)