Colonial Korea – Geumsansa Temple

Temple History

Geumsansa Temple, which means “Golden Mountain Temple” in English, is located in a flat river valley on the western slopes of Moaksan Provincial Park in Gimje, Jeollabuk-do. Geumsansa Temple was first established in either 599 or 600 A.D., depending on the source, during the reign of King Beop of Baekje (r. 599-600 A.D.). When it was first built, it was rather unassuming and nothing like it is today. It wasn’t until 762 A.D., under the guidance of the monk Jinpyo (8th century), that Geumsansa Temple was rebuilt. Geumsansa Temple was rebuilt over a six year period. Numerous buildings at the temple were rebuilt at this time including the original Mireuk-jeon Hall, which was built in 766 A.D.

There’s an interesting legend that surrounds the reconstruction of Geumsansa Temple by Jinpyo. When Jinpyo decided to dedicate a temple to Mireuk-bul (The Future Buddha), he didn’t know the best location for this temple. So while looking around Jeonju, he met Yongwang (The Dragon King). Jinpyo was presented with a jade robe by Yongwang. After, Yongwang guided Jinpyo to the site of a ruined temple at the foot of Mt. Moaksan (793m). The ruined location was said to be the home of a powerful female Sanshin (Mountain Spirit). Miraculously, and seemingly from out of thin air, men and women arrived to offer assistance in reconstructing the former temple. The temple was rebuilt over the span of a couple of days; and it was at this time that Mireuk-bul appeared and granted Jinpyo his final ordination as a Buddhist monk. Mireuk-bul also gave Jinpyo some sari (crystallized remains) of the Buddha, Seokgamoni-bul. To help commemorate this event, Jinpyo built the enormous Mireuk-jeon Hall with three standing bronze statues inside. Jinpyo also purportedly built the Gyedan (Precepts Altar) at Geumsansa Temple. Housed inside the stupa on top of the Gyedan are the sari of the Buddha. Perhaps a stretch, but a wonderful foundation myth all the same.

Later, King Gyeon Hwon, of Later Baekje, or “Hubaekje” in Korean, who reigned from 900 to 935 A.D., had parts of Geumsansa Temple repaired. Ironically, he was later held captive at Geumsansa Temple after his son, King Gyeon Singeom, usurped his father’s throne and had him imprisoned. The temple underwent numerous changes during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). King Munjong of Goryeo’s (r.1046-1083) teacher, the monk Hyedeok (1038-1096), further renovated the look of the temple during this time. Then, in the waning years of the Goryeo Dynasty, Weonmyeong-daesa (1262-1330) had the temple rebuilt, once more.

Even after the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) came to power, the Mireuk-bul tradition at the temple remained strong. In 1592, Geumsansa Temple was made the headquarters by the government to oversee all temples in the region for Jeollanam-do Province. During the initial attack of the Korean Peninsula by the Japanese as part of the Imjin War in 1592-1593, it saw Geumsansa Temple used as a training ground for Buddhist monks known as the Righteous Army. In total, over a thousand monks were led by the monk Noemuk to help defend the Korean Peninsula from the Japanese aggressors. It was during the second wave of the Imjin War from 1597-1598, which is known as “Second War of Jeong-yu,” that Geumsansa Temple became a headquarters for the Righteous Army. Tragically, not only were forty regional hermitages destroyed, but so too was Geumsansa Temple and the famed Mireuk-jeon Hall.

The restoration of Geumsansa Temple began in 1601, and it was completed over a thirty year period ending in 1635. Most of the temple buildings, including the rebuilt Mireuk-jeon Hall, date back to this period of time. And it’s because of these efforts that Geumsansa Temple is one of the largest Buddhist temples in Korea.

In total, Geumsansa Temple is home to one National Treasure, ten Korean Treasures, one Historic Site, and one National Registered Cultural Heritage.

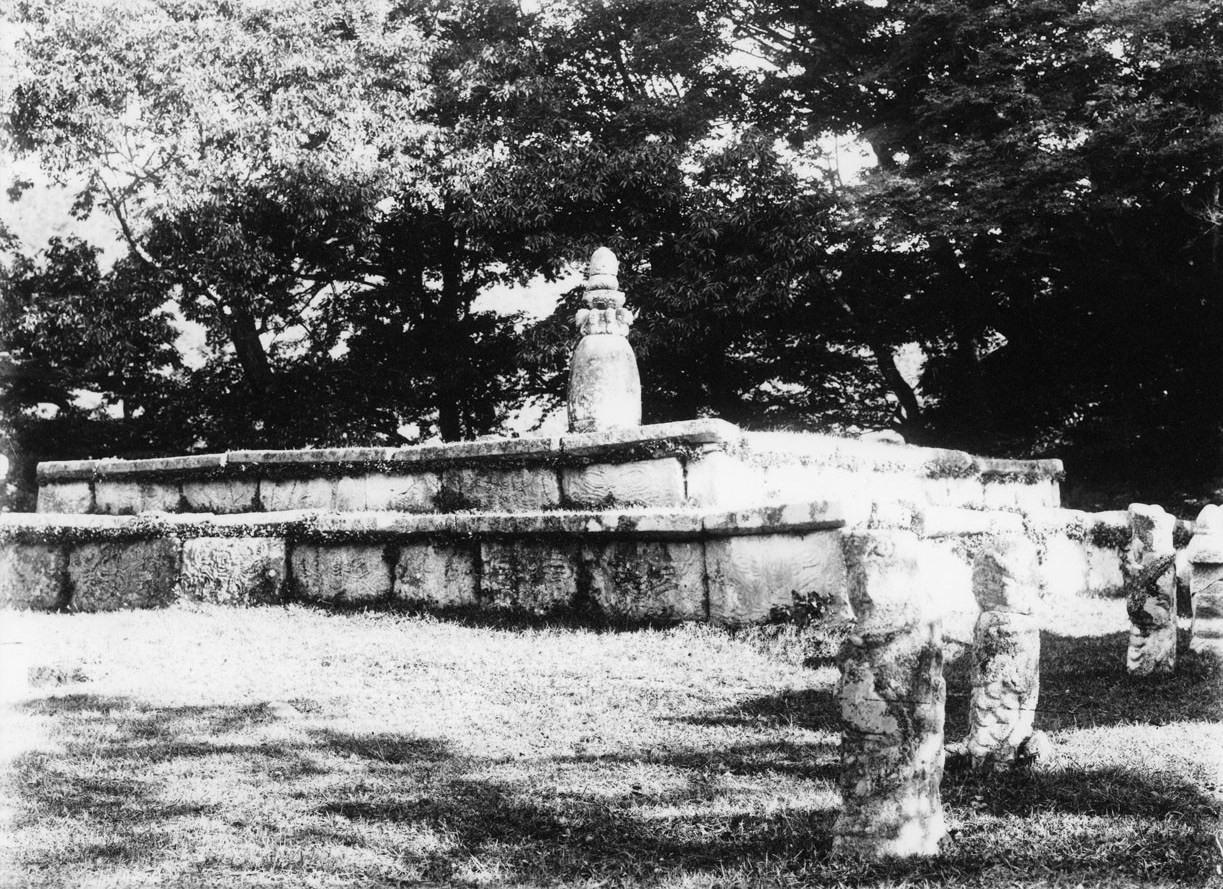

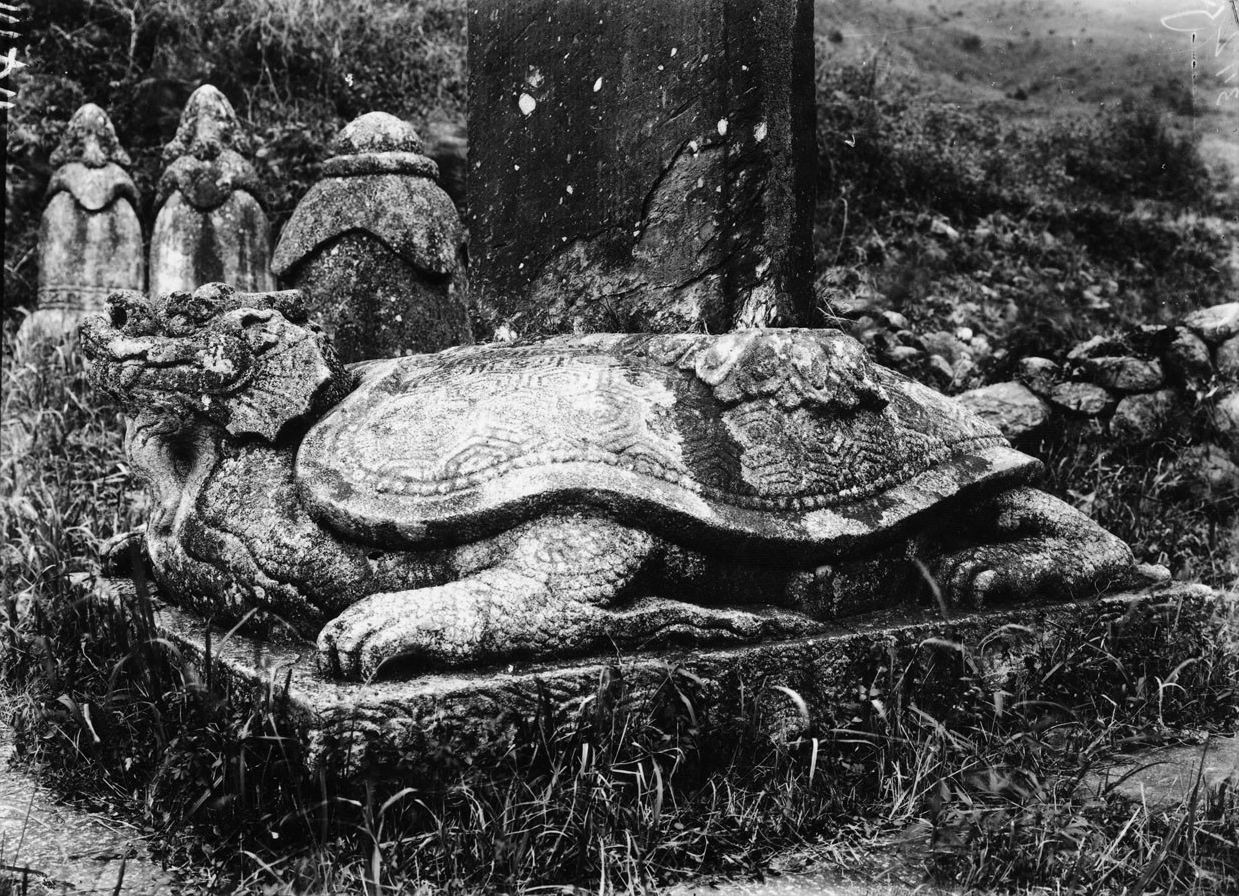

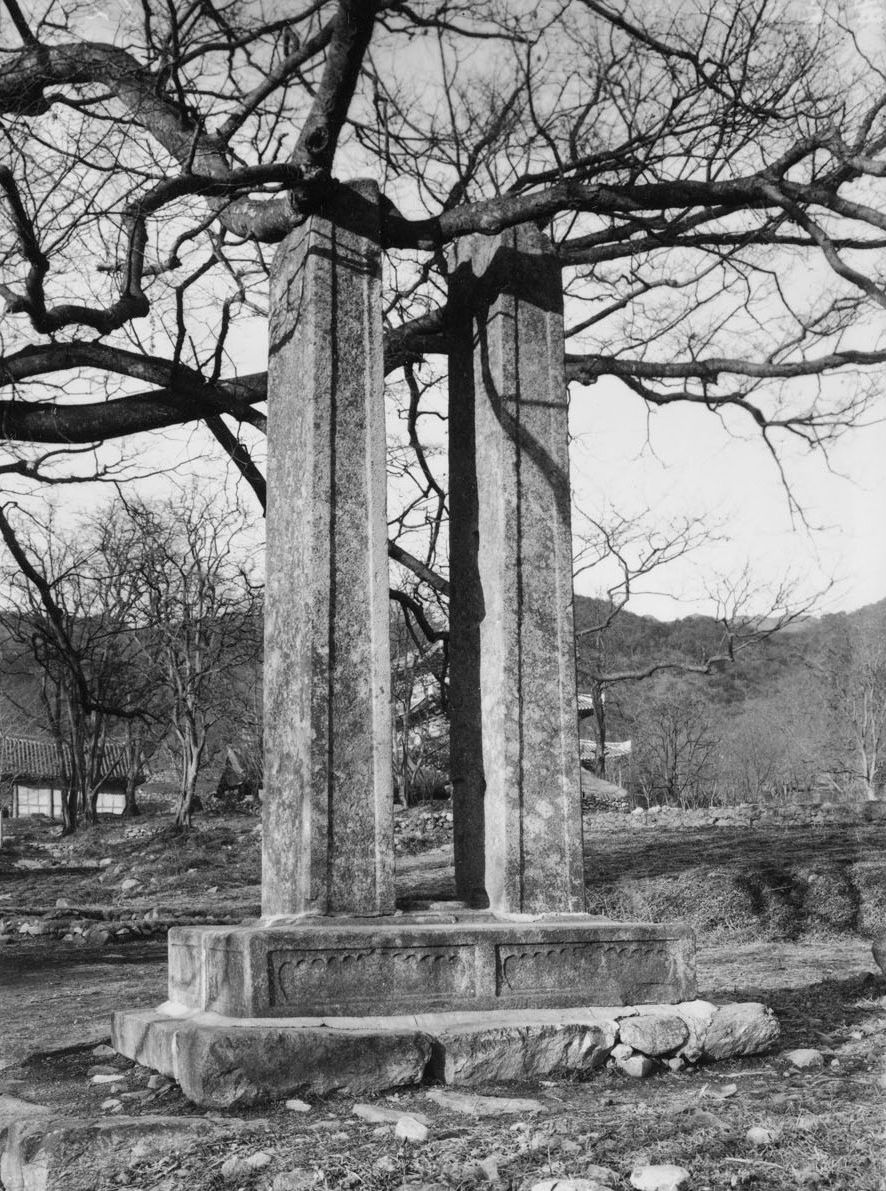

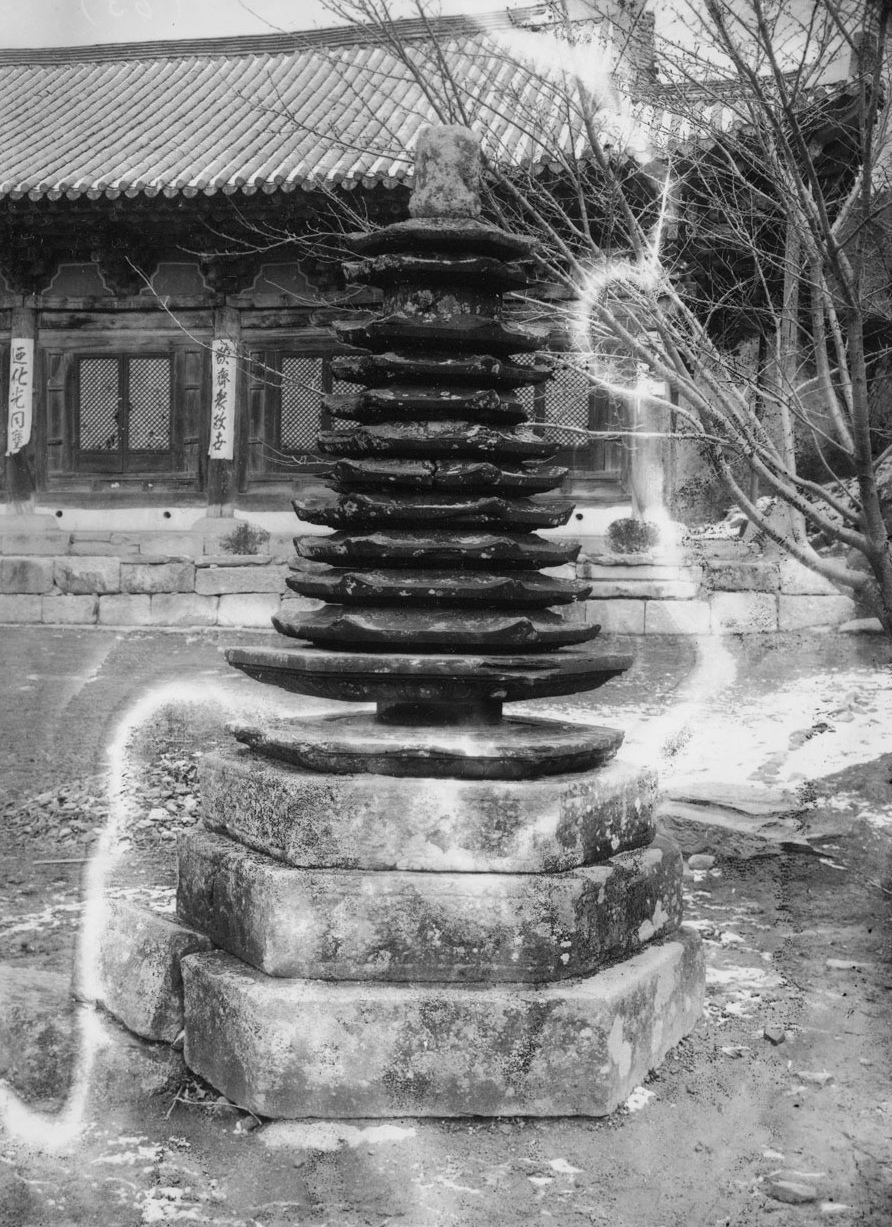

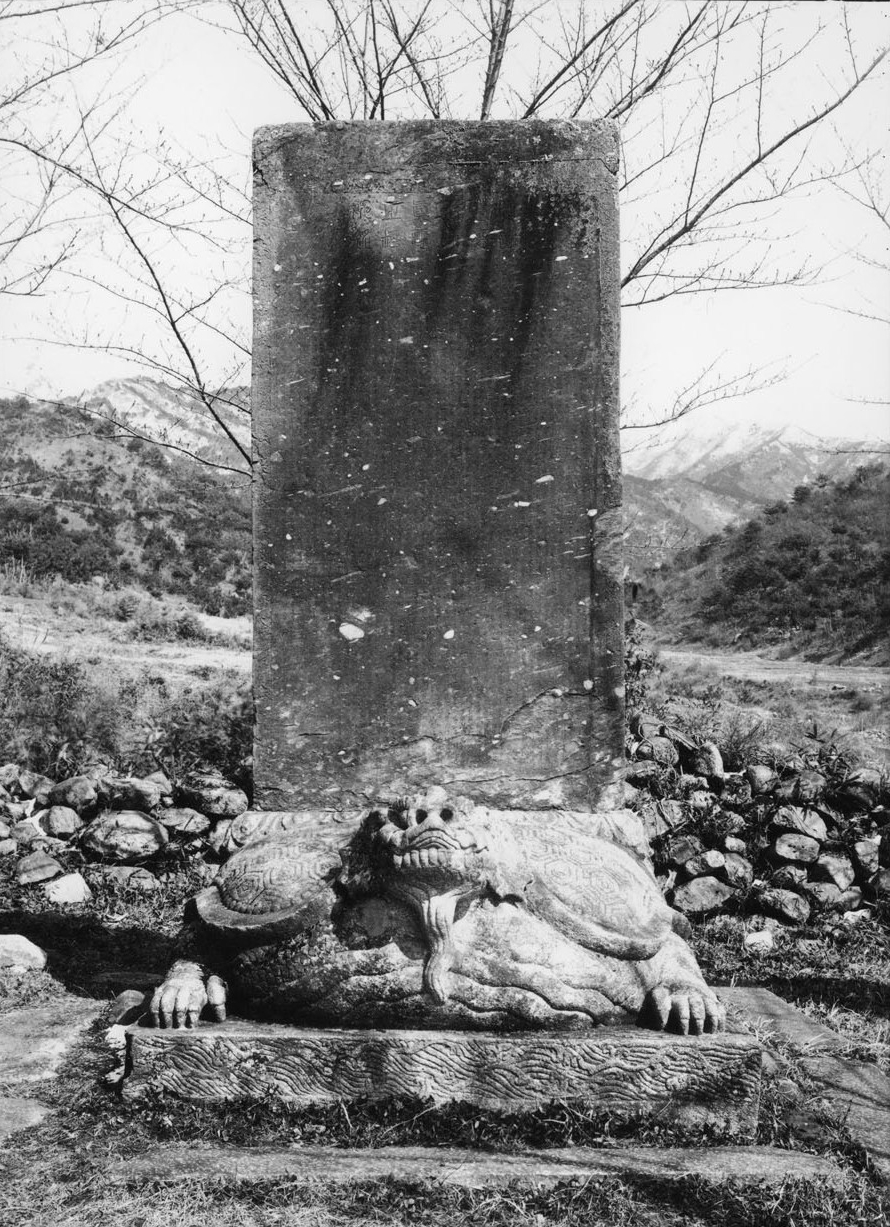

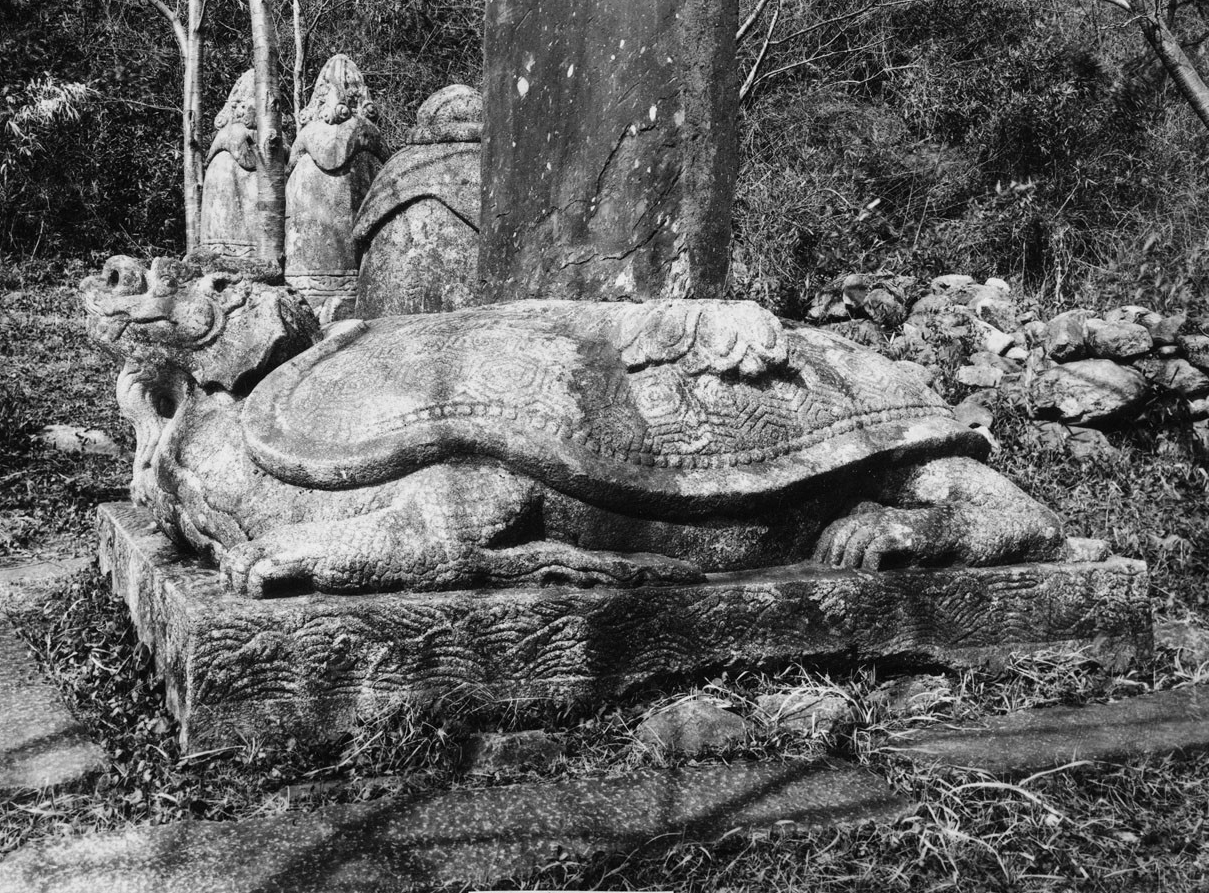

Colonial Era Photography

It should be noted that one of the reasons that the Japanese took so many pictures of Korean Buddhist temples during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945) was to provide images for tourism and illustrations in guidebooks, postcards, and photo albums for Japanese consumption. They would then juxtapose these images of “old Korea” with “now” images of Korea. The former category identified the old Korea with old customs and traditions through grainy black-and-white photos.

These “old Korea” images were then contrasted with “new” Korea images featuring recently constructed modern colonial structures built by the Japanese. This was especially true for archaeological or temple work that contrasted the dilapidated former structures with the recently renovated or rebuilt Japanese efforts on the old Korean structures contrasting Japan’s efforts with the way that Korea had long neglected their most treasured of structures and/or sites.

This visual methodology was a tried and true method of contrasting the old (bad) with the new (good). All of this was done to show the success of Japan’s “civilizing mission” on the rest of the world and especially on the Korean Peninsula. Furthering this visual propaganda was supplemental material that explained the inseparable nature found between Koreans and the Japanese from the beginning of time.

To further reinforce this point, the archaeological “rediscovery” of Japan’s antiquity in the form of excavated sites of beautifully restored Silla temples and tombs found in Japanese photography was the most tangible evidence for the supposed common ancestry both racially and culturally. As such, the colonial travel industry played a large part in promoting this “nostalgic” image of Korea as a lost and poor country, whose shared cultural and ethnic past was being restored to prominence once more through the superior Japanese and their “enlightened” government. And Geumsansa Temple played a part in the propagation of this propaganda, especially since it played such a prominent role in Korean Buddhist history and culture. Here are a collection of Colonial era pictures and drawings of Geumsansa Temple through the years.

Pictures of Colonial Era Geumsansa Temple

1910

Pictures of Colonial Era Geumsansa Temple

1934

Pictures of Colonial Era Geumsansa Temple

Specific Dates Unknown (1909-1945)