Colonial Korea – Seokguram Hermitage

Hermitage History

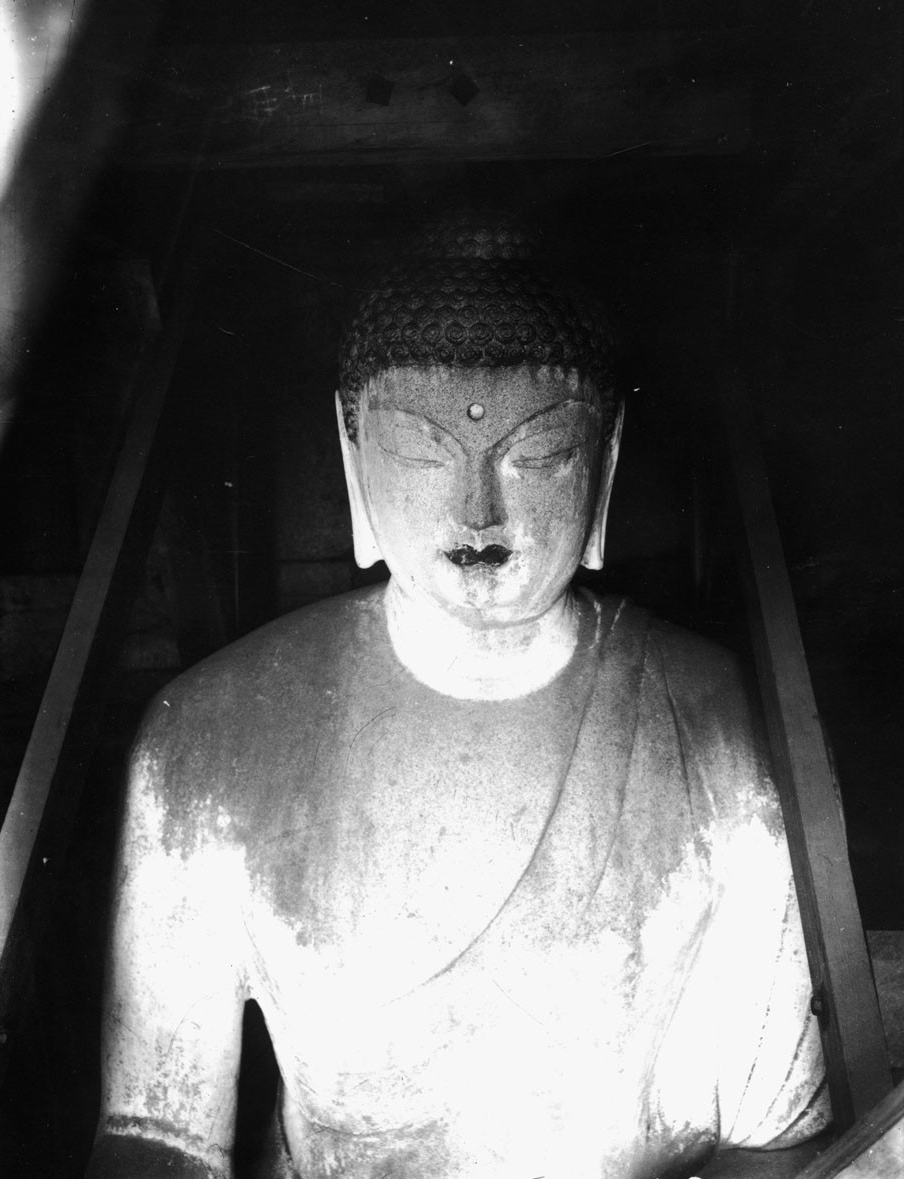

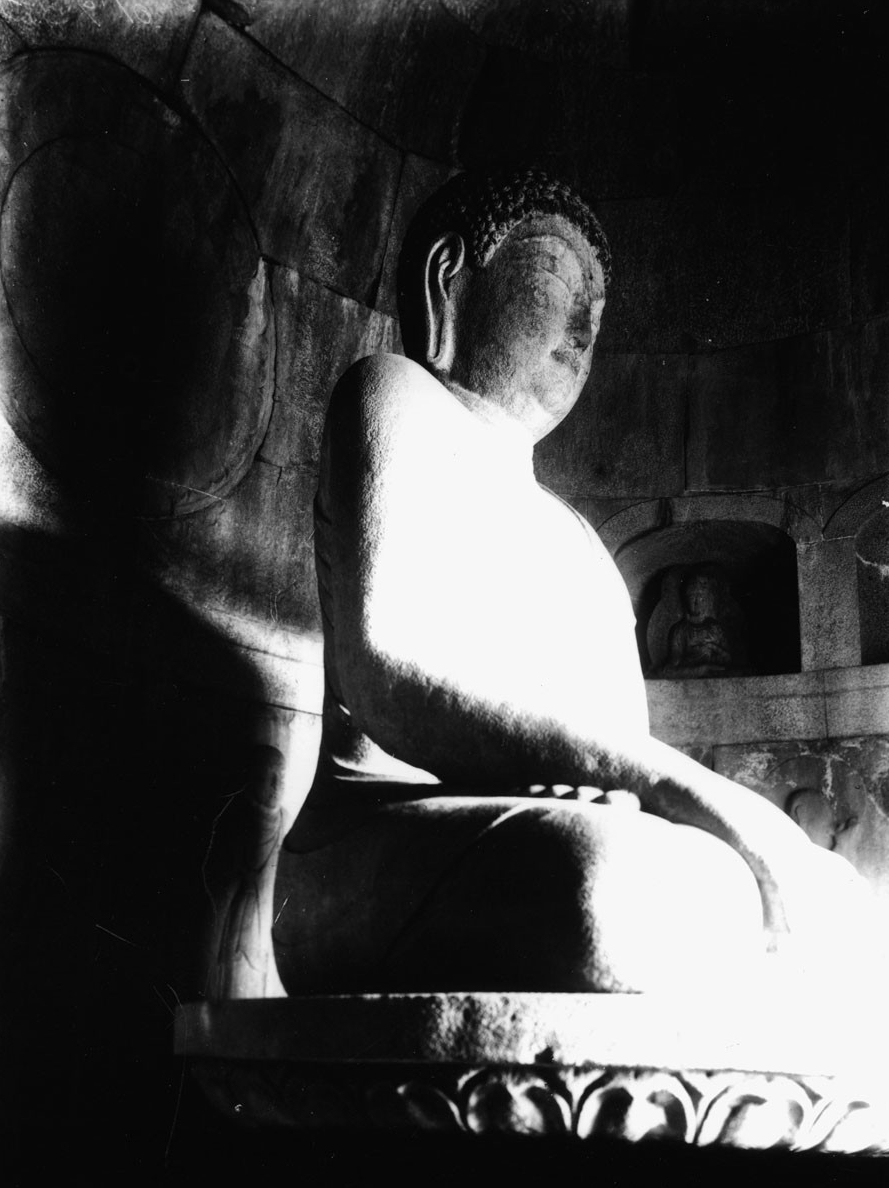

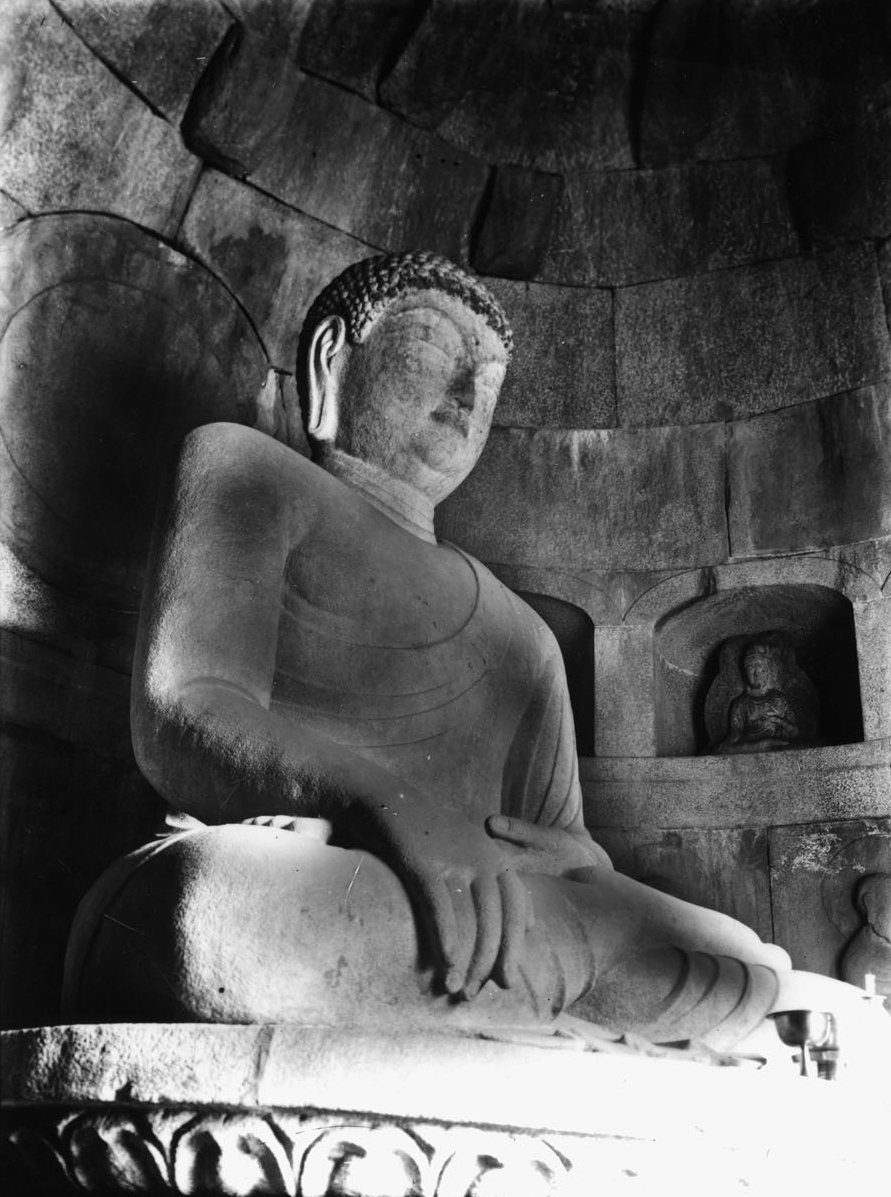

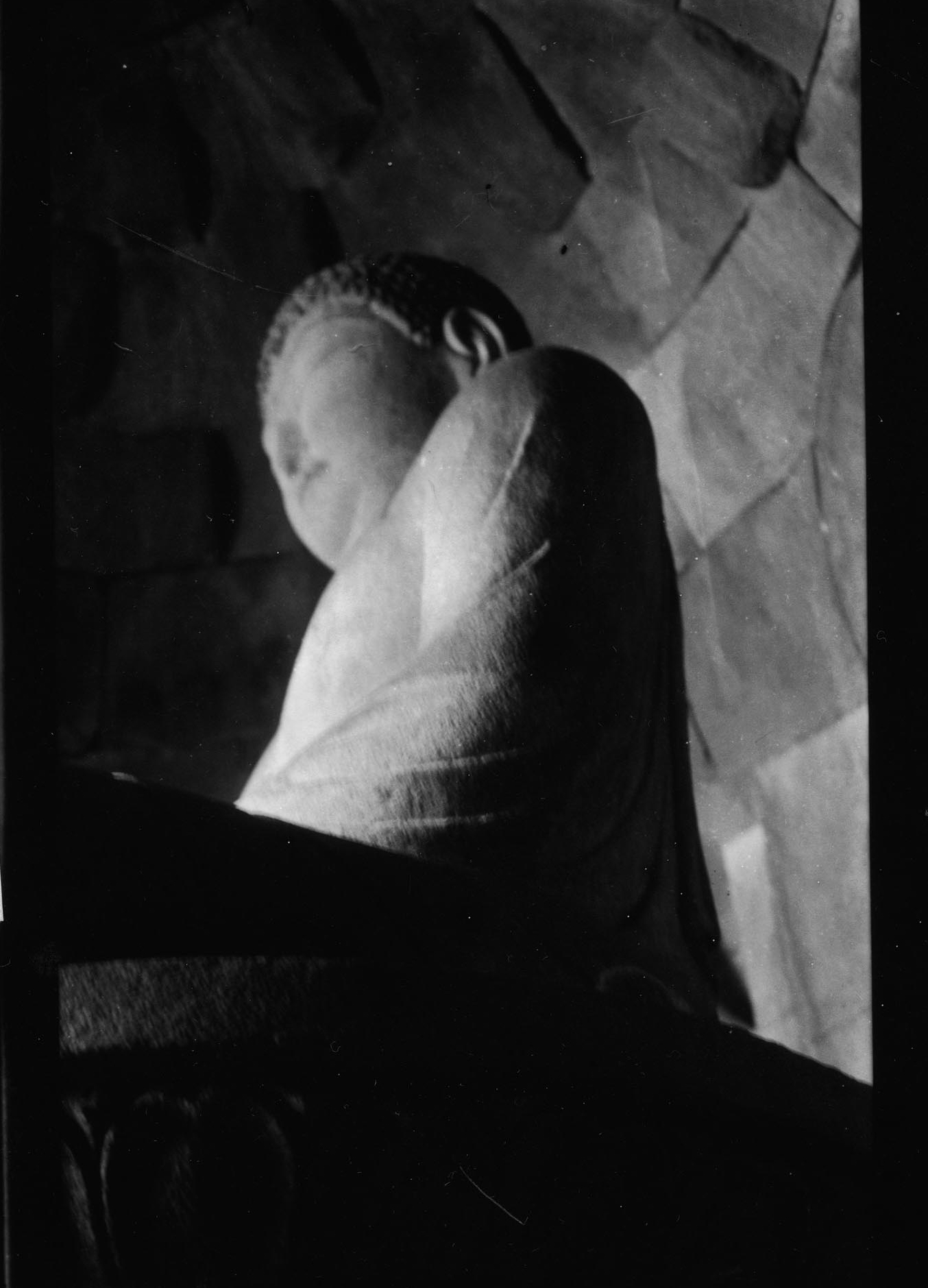

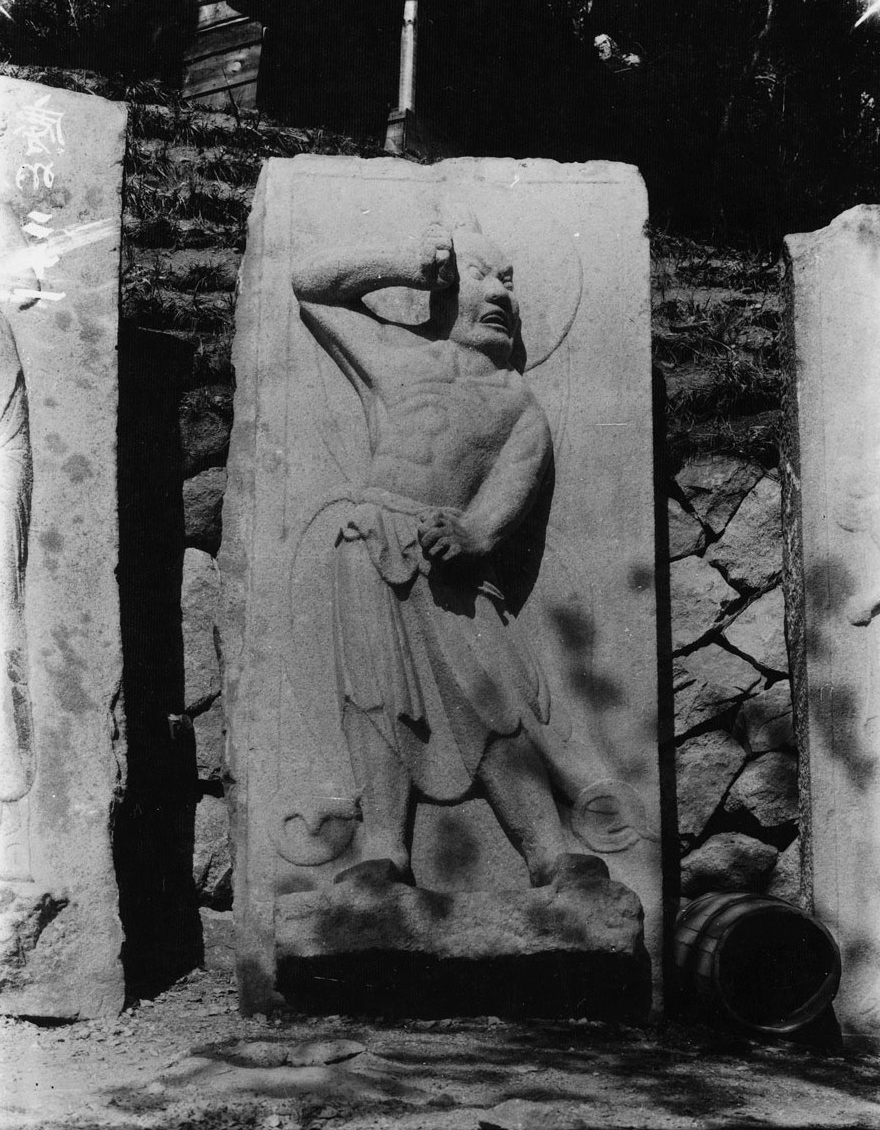

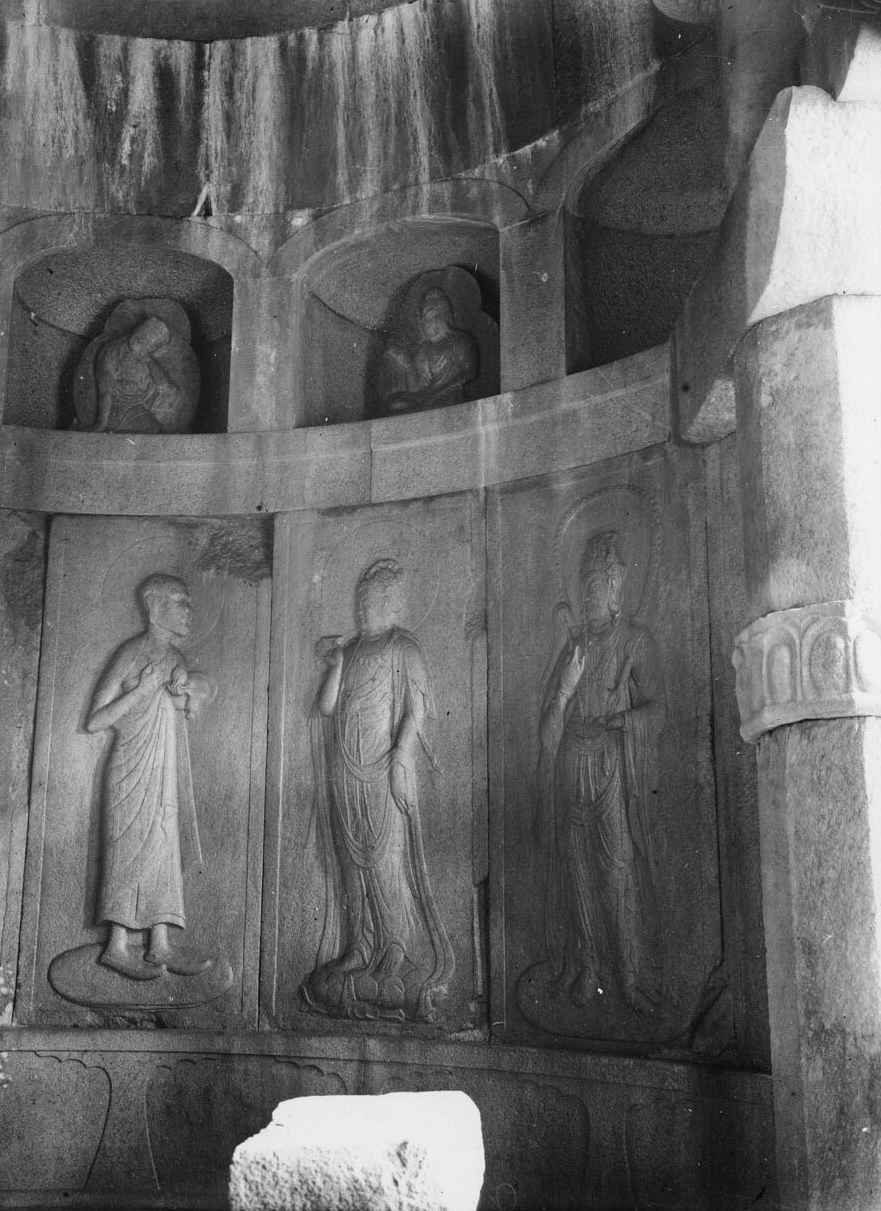

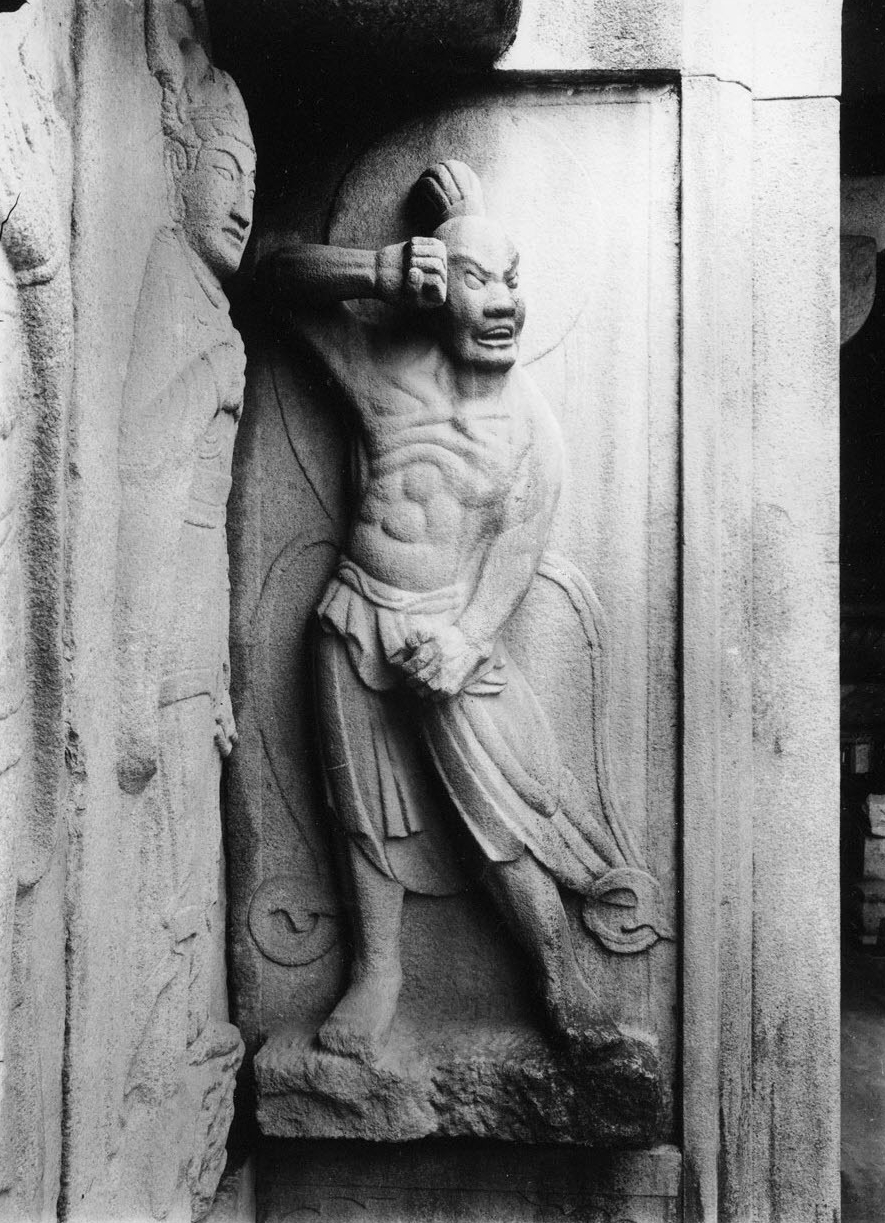

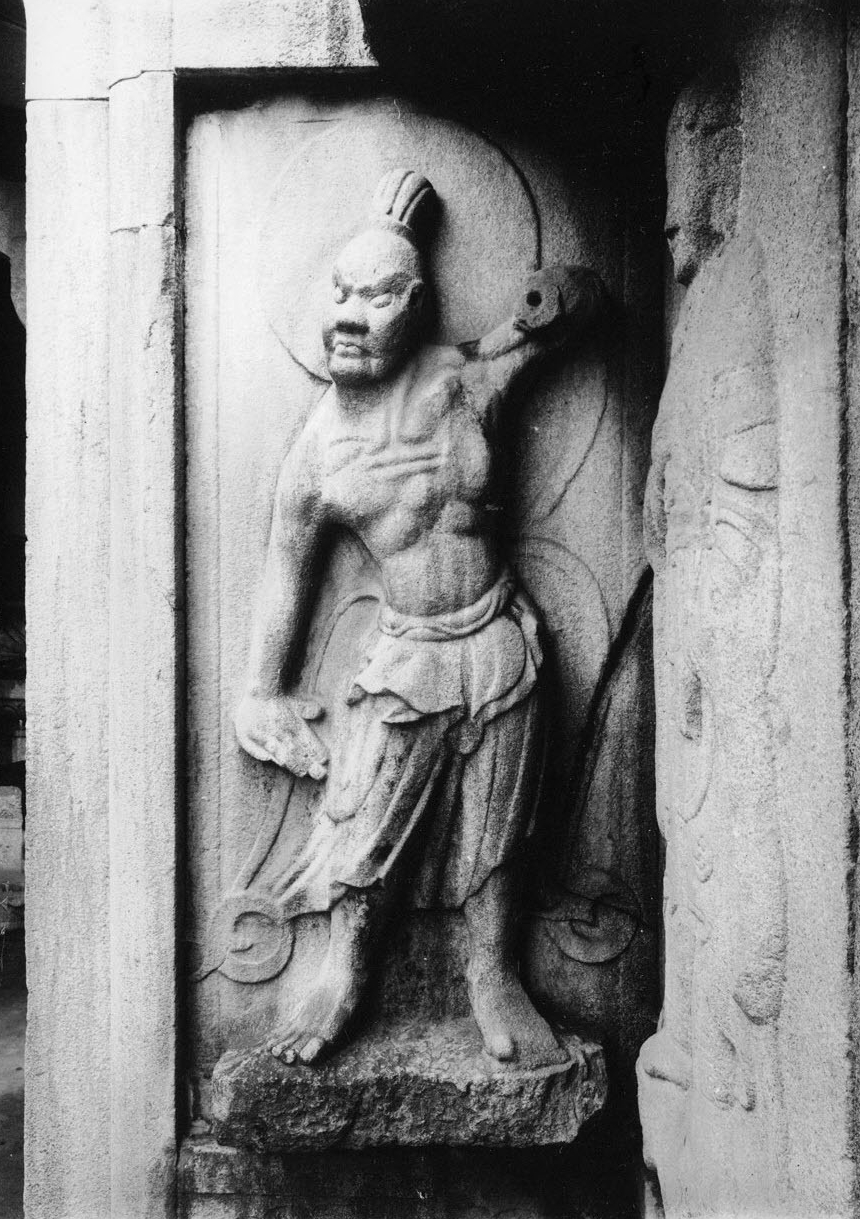

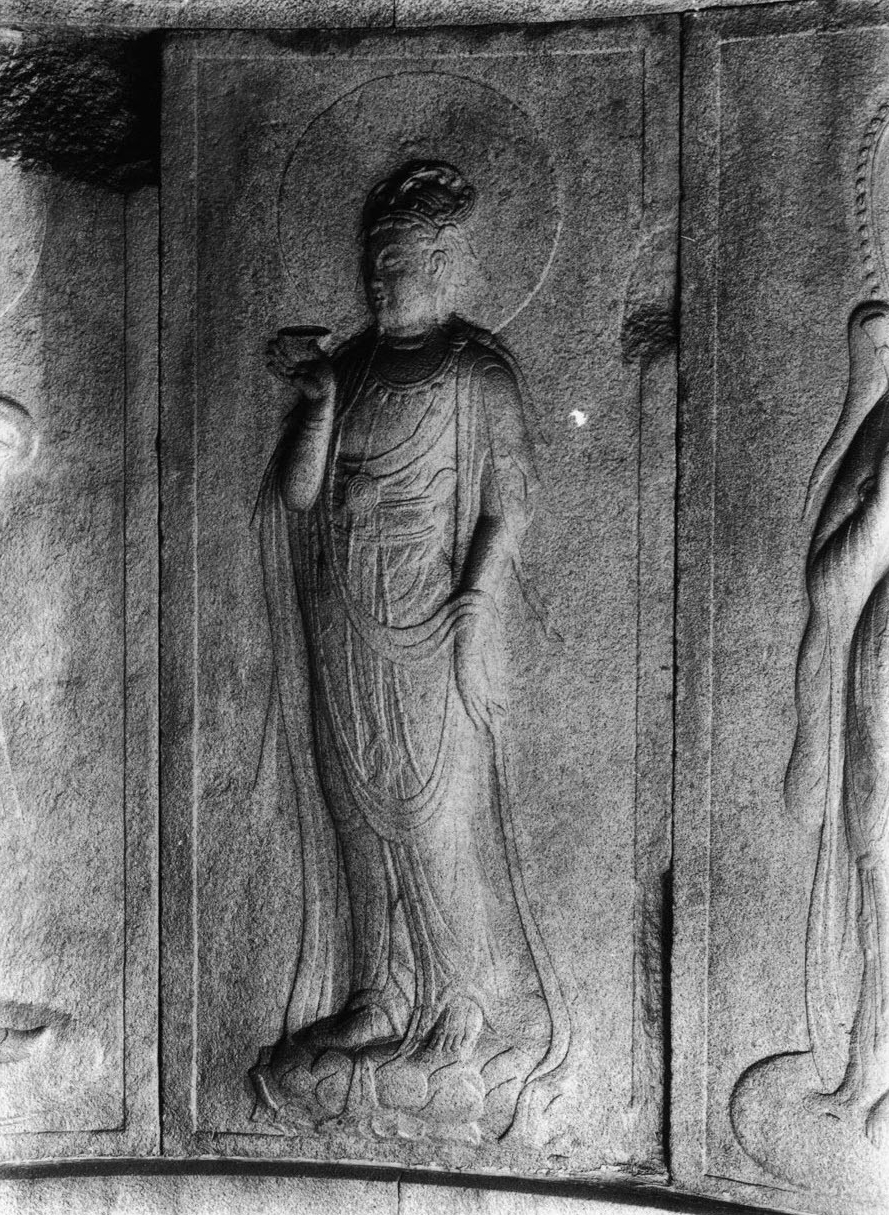

Seokguram Hermitage on Mt. Tohamsan in eastern Gyeongju houses the most famous statue in all of Korea. In English, Seokguram Hermitage means “Stone Cave Hermitage.” Not only is it a UNESCO World Heritage Site as of 1995 alongside Bulguksa Temple, it’s also National Treasure #24. Construction on Seokguram Grotto first started in 751 A.D. by Kim Daeseong (700-774 A.D.), who was the chief minister of Silla. The grotto was completed in 774 A.D. by the Silla court shortly after Kim’s death. According to the “Samguk Yusa,” or “Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms” in English, neighbouring Bulguksa Temple and the Seokguram Grotto were built to honor Kim Daeseong’s parents. Seokguram Grotto was built to honor Kim’s parents from his former life, while Bulguksa Temple was built to honor Kim’s parents from his present life.

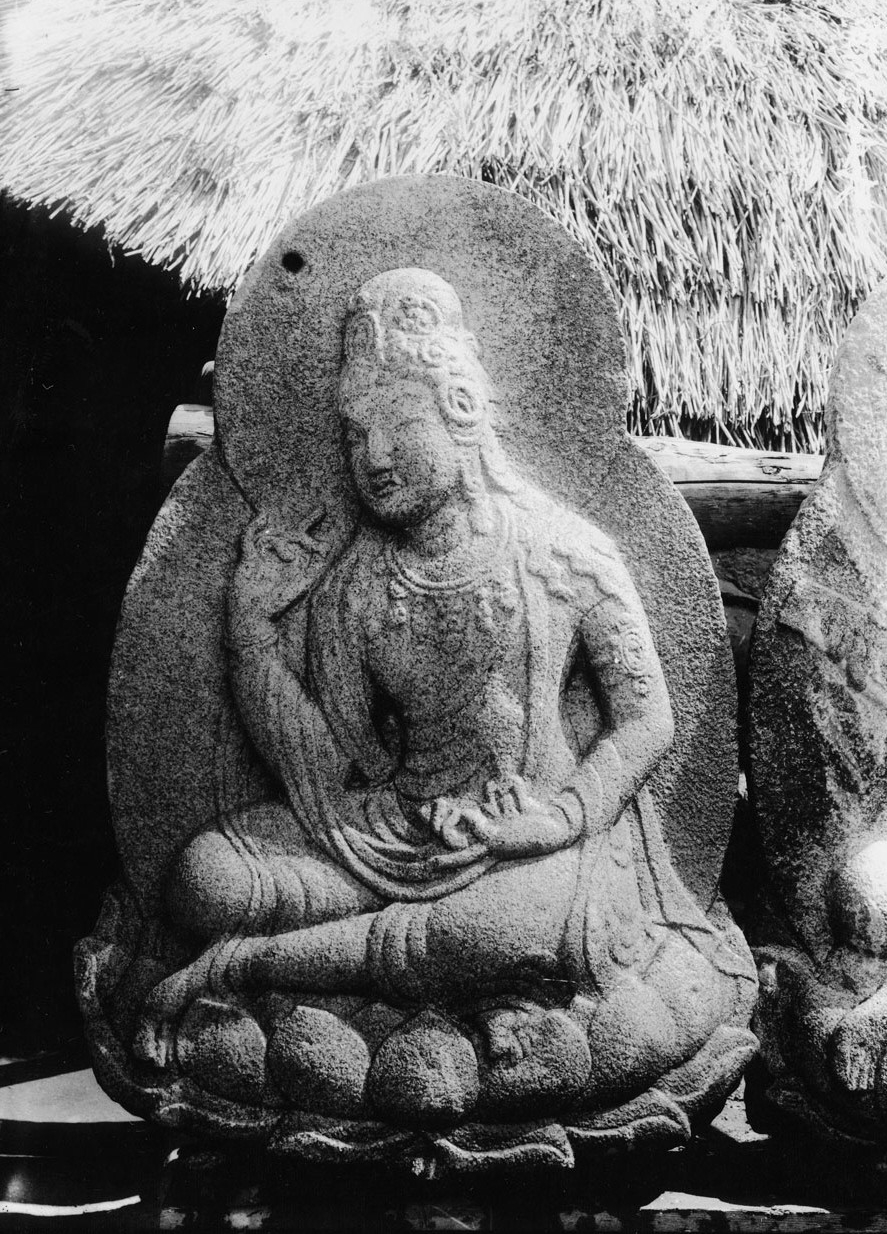

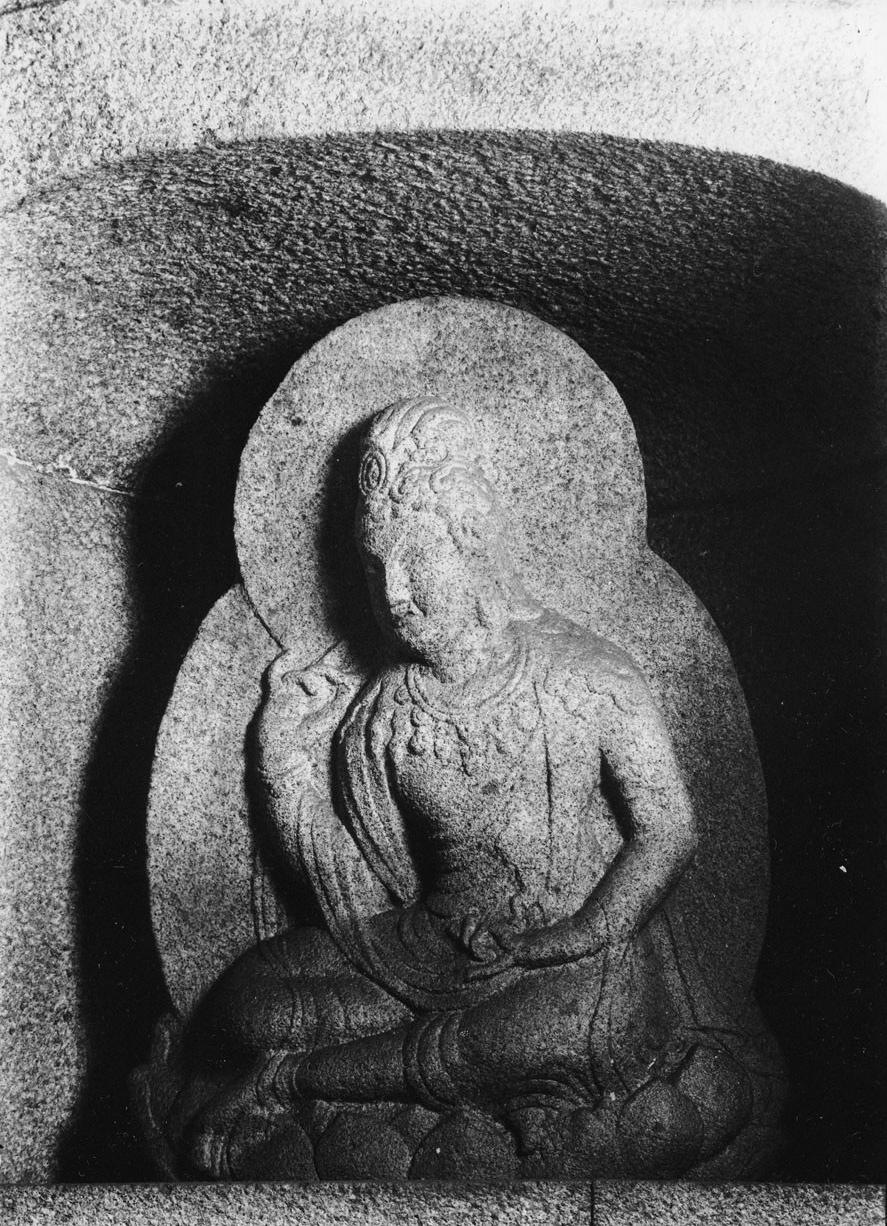

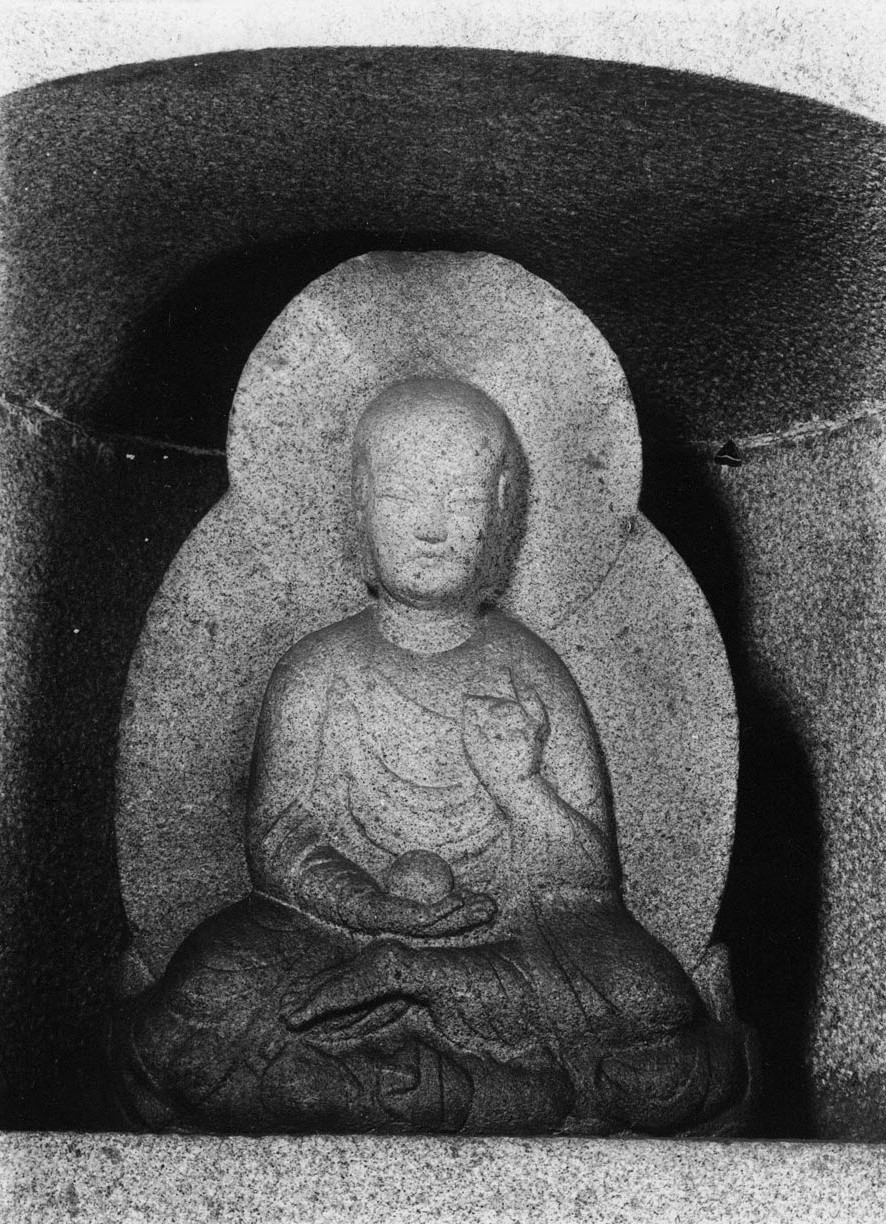

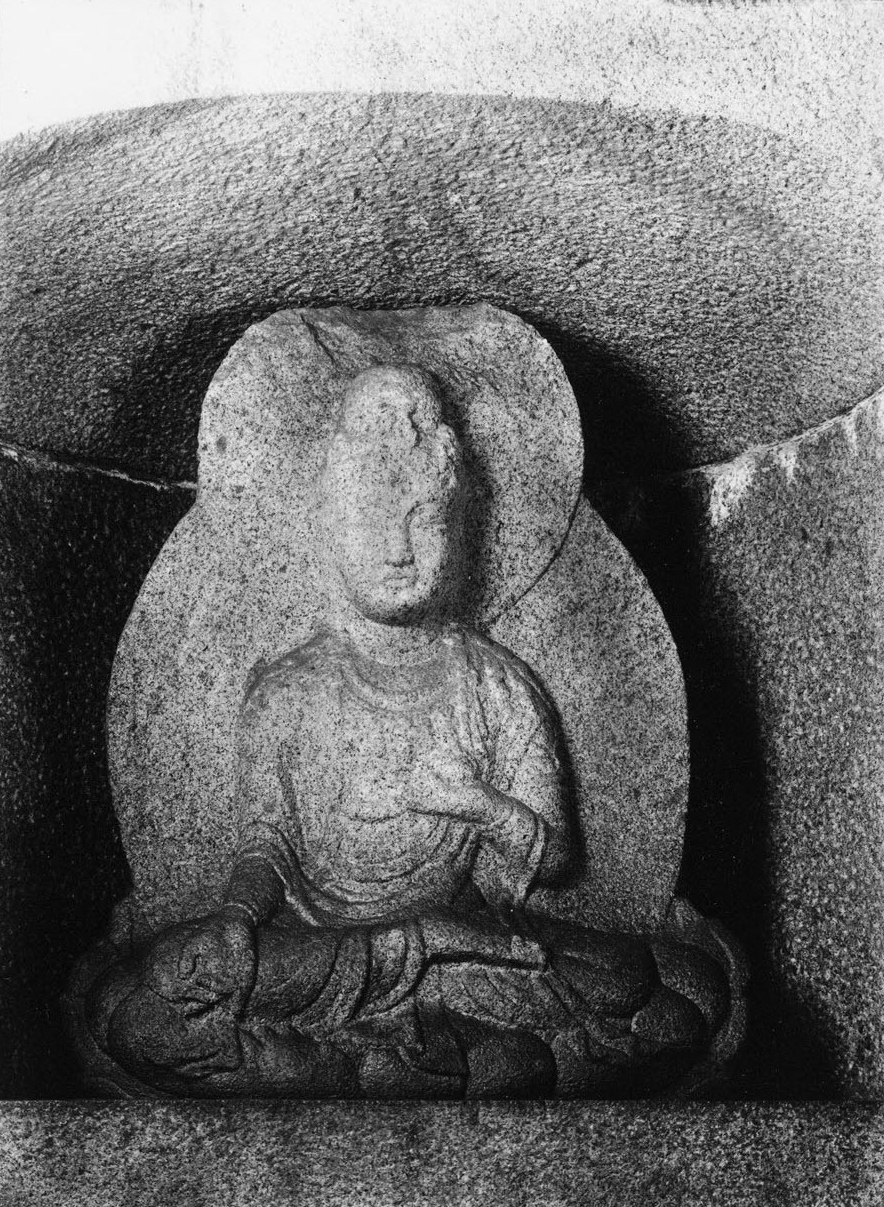

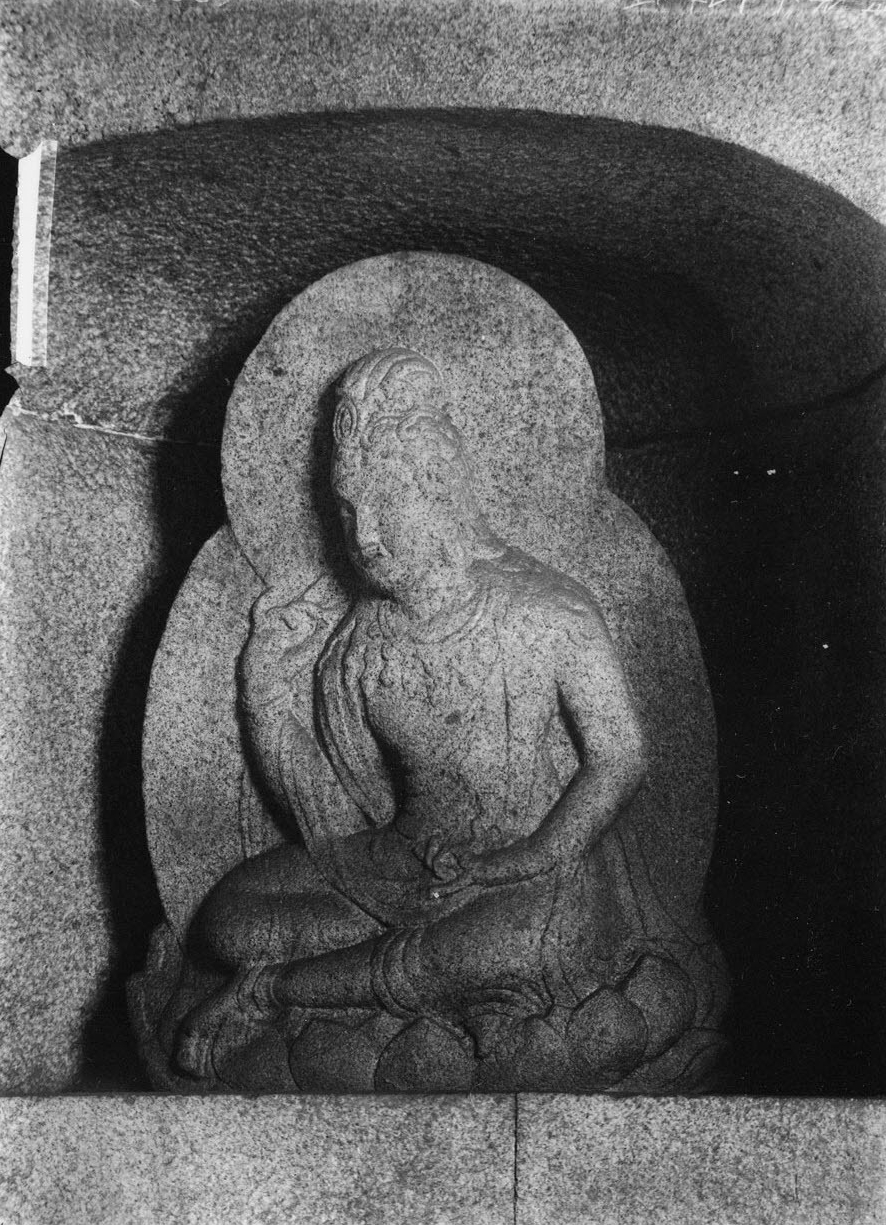

The Seokguram Grotto is an artificial cave that follows in the tradition of carving images of the Buddha on stones, natural caves, mountain walls, and stupas in India. This tradition, as Buddhism migrated eastward, was practiced in China and then in Korea. However, because of the geological make-up of the Korean Peninsula, which contains an abundance of hard granite, both mountain carvings and cave images were extremely difficult to create. With all this in mind, Seokguram Grotto is an artificial cave.

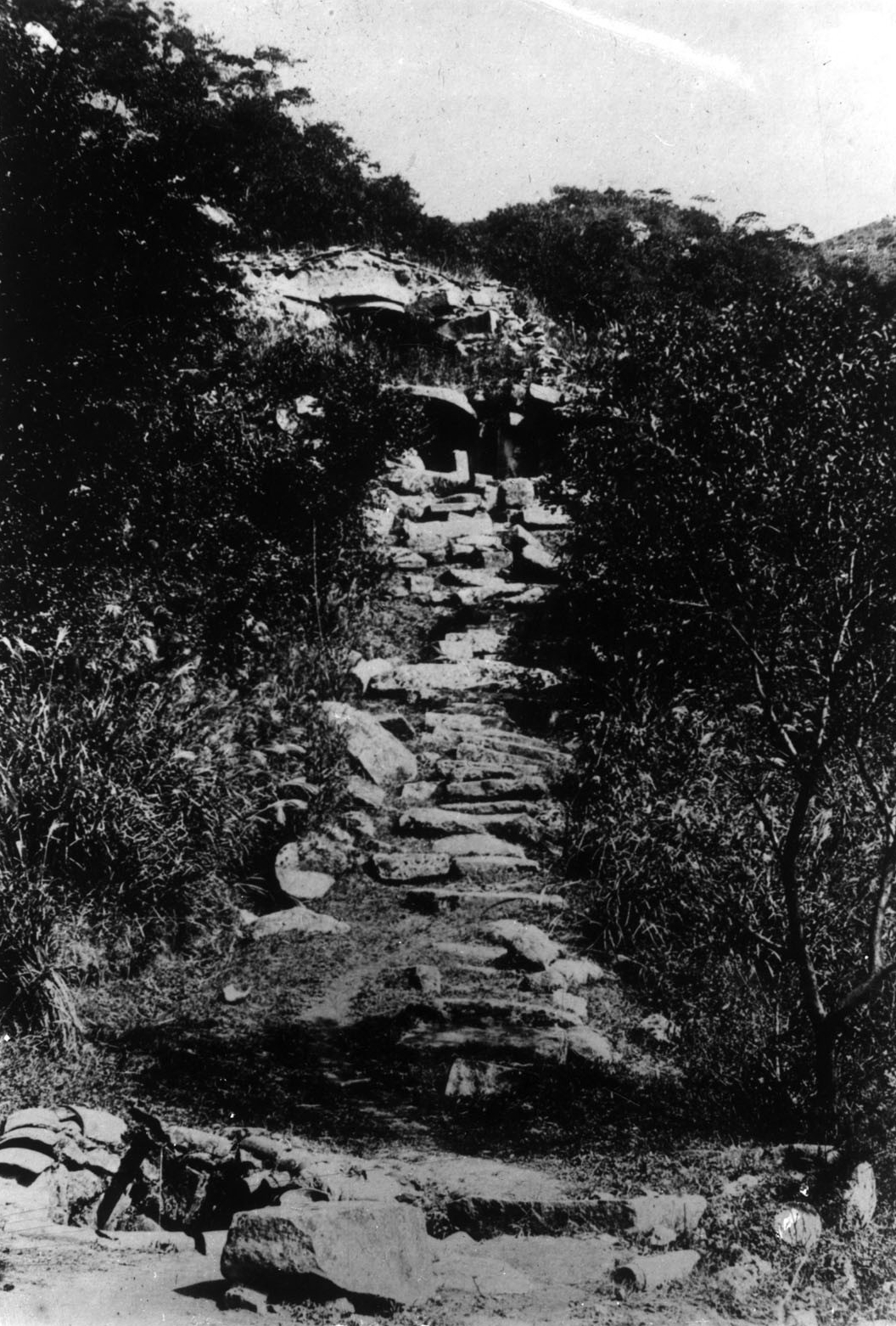

Throughout the years, Seokguram Hermitage has undergone numerous repairs. Eventually, Seokguram Grotto fell into disrepair largely as a result of the oppressive Confucian-oriented policies of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) towards Korean Buddhism. Except for locals, who probably still visited the grotto, Seokguram Grotto wasn’t re-discovered until 1909, when a travelling postman found it.

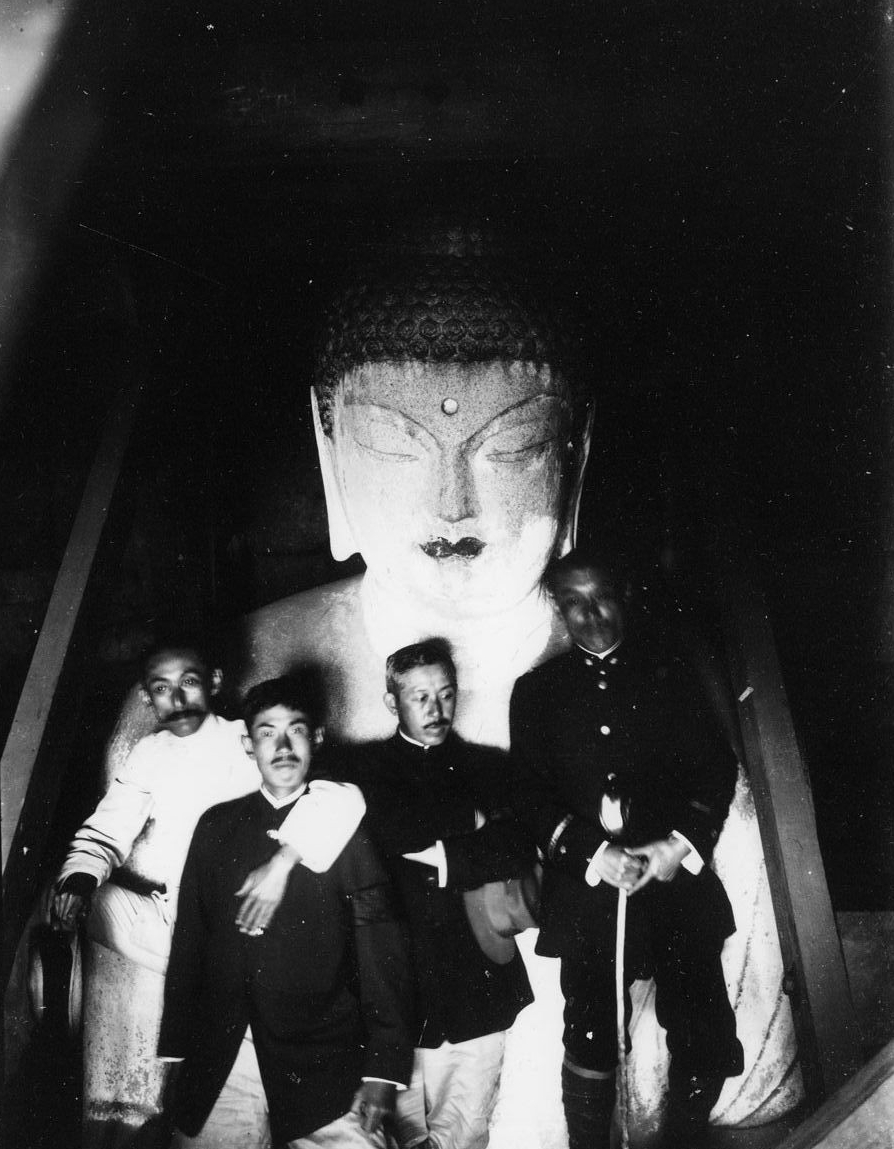

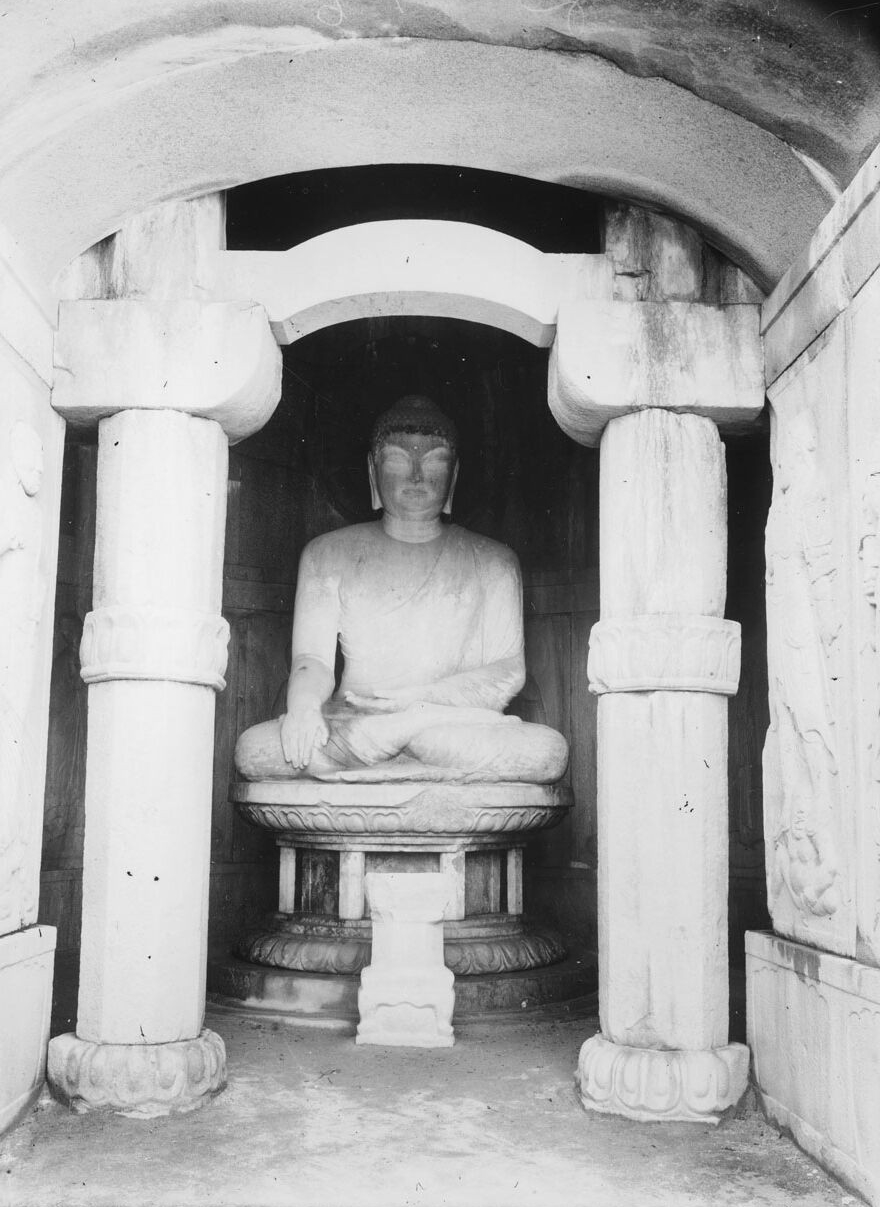

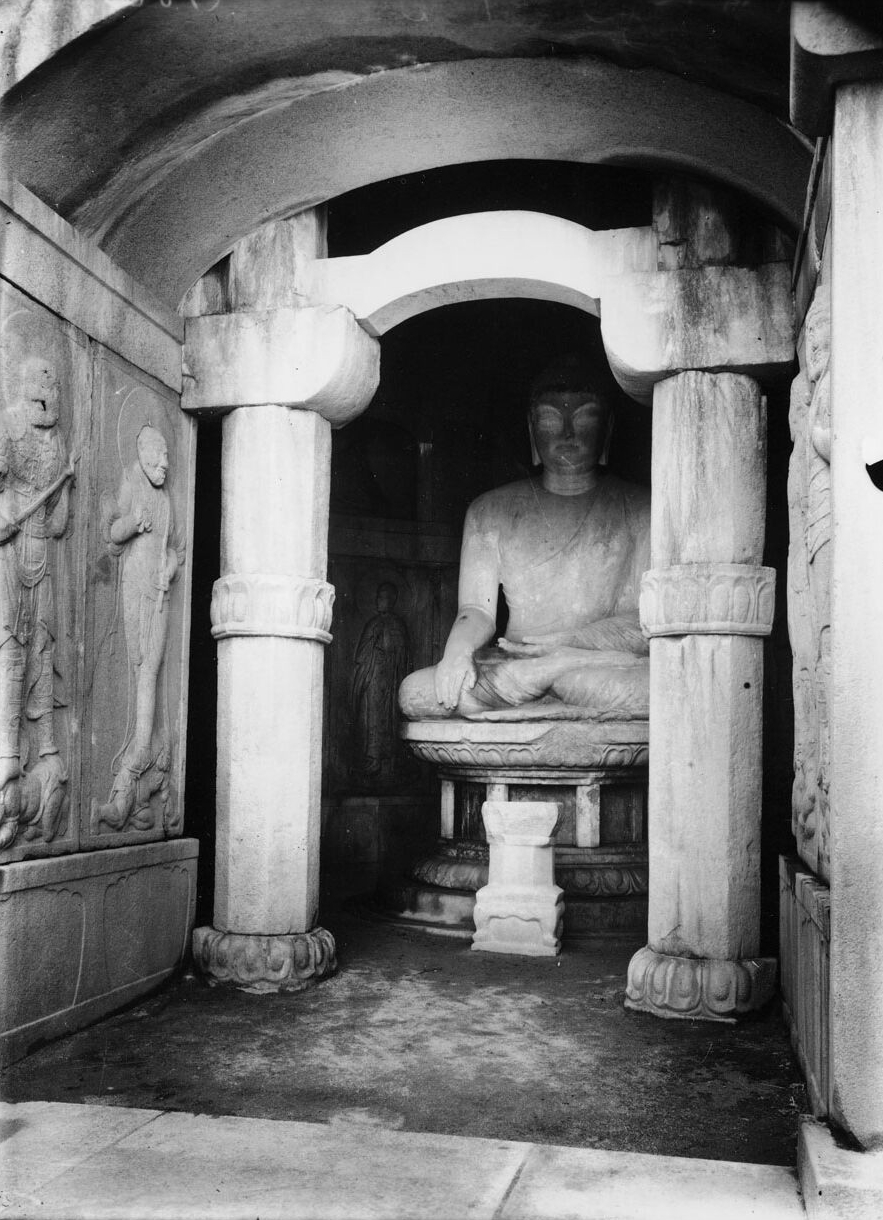

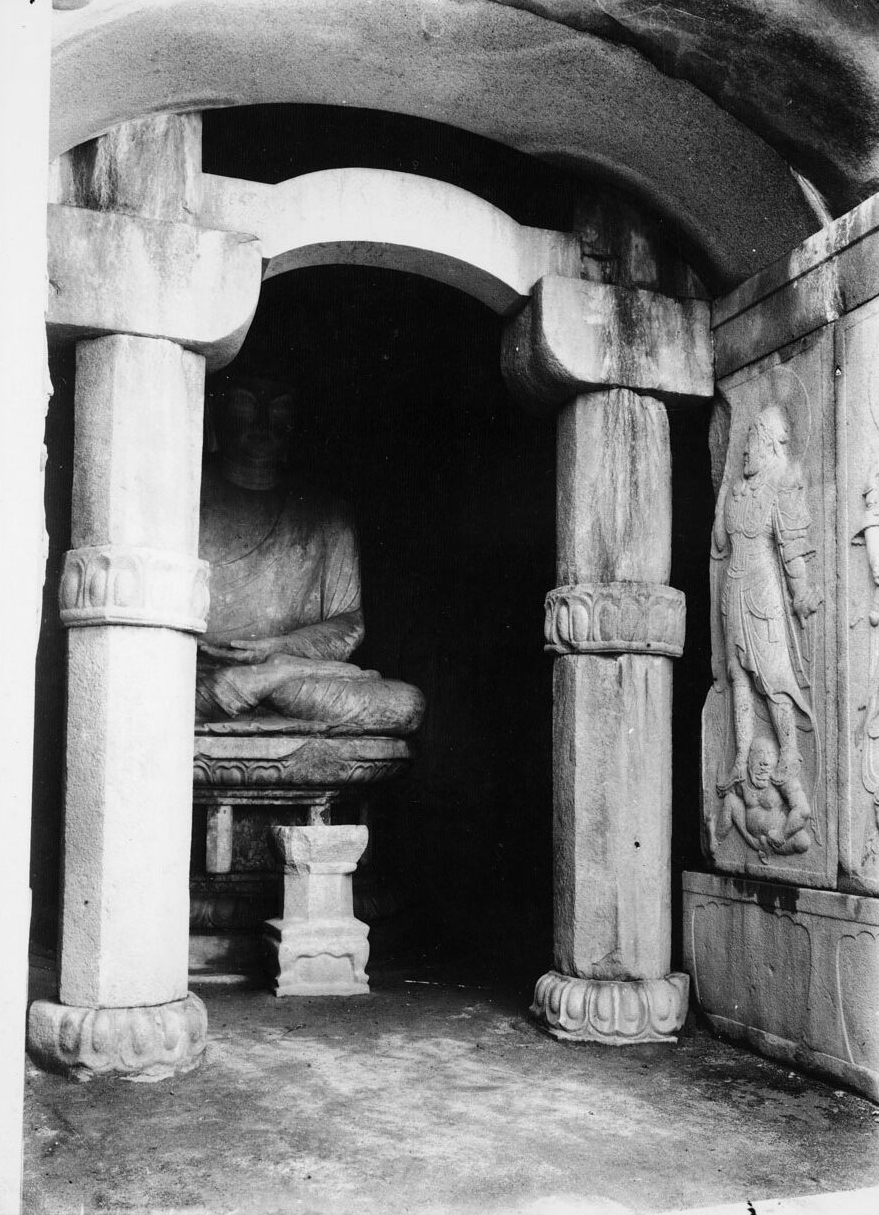

Eventually, word got back to the Japanese authorities in Seoul. That same year, Resident-General Sone Arasuke (1849-1910) paid a highly publicized official visit to the Seokguram Grotto. Archaeologically and architecturally, the grotto was investigated by Japanese authorities led by Dr. Sekino Tadashi (1868-1935), who wrote a report on the condition of the Seokguram Grotto in 1910. In this report, Sekino expressed concern that rainwater was washing silt down from the mountain which was causing the front arch capstones to collapse. As a result, the seated central Buddha figure was being exposed to the elements.

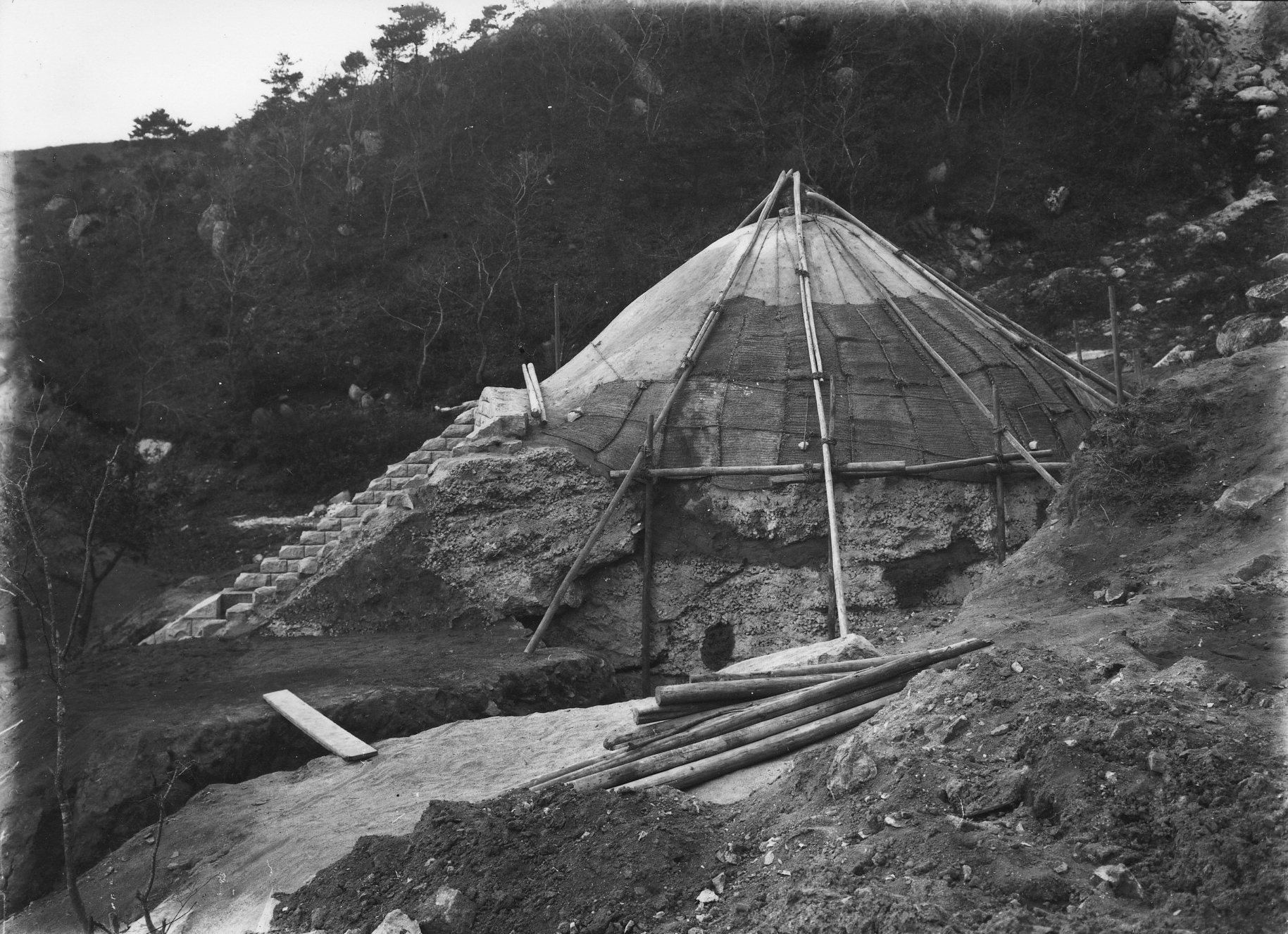

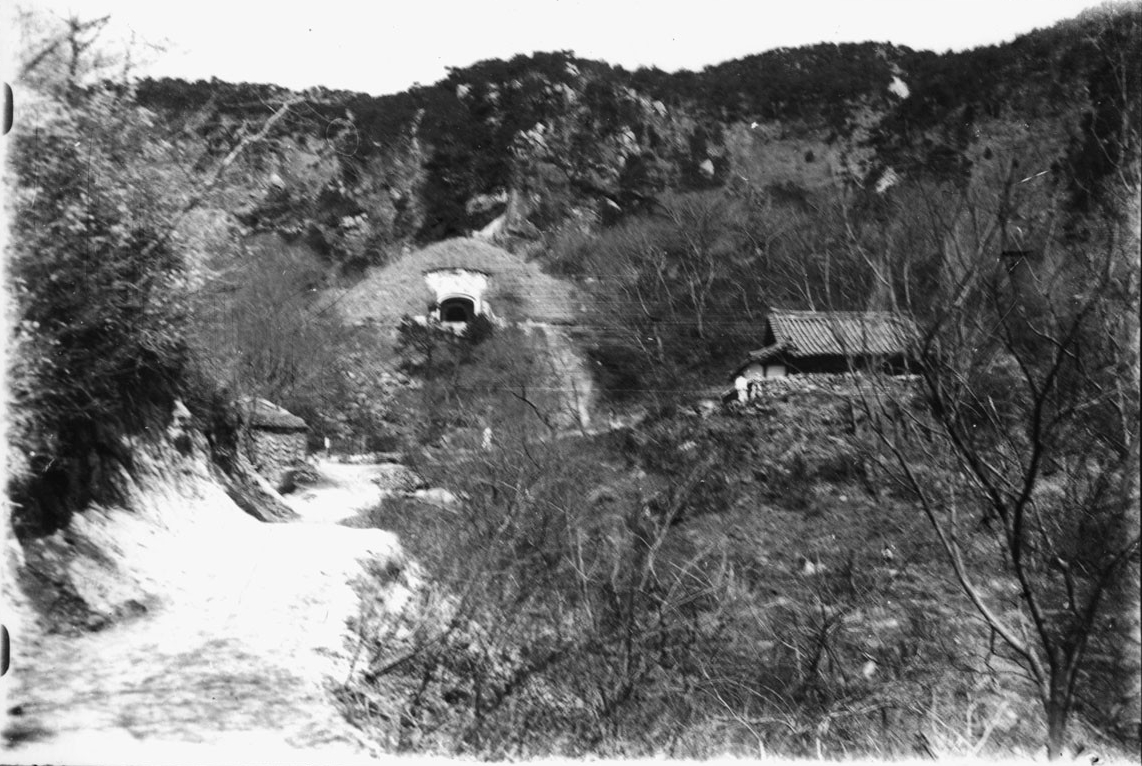

Through Sekino’s report, and the Japanese authorities need and want to use tourism and Buddhism as a way to help potentially unite Koreans and Japanese during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-45), this led to several reconstruction projects on the Seokguram Grotto that took place over sixteen years starting in 1913 and ending in 1928.

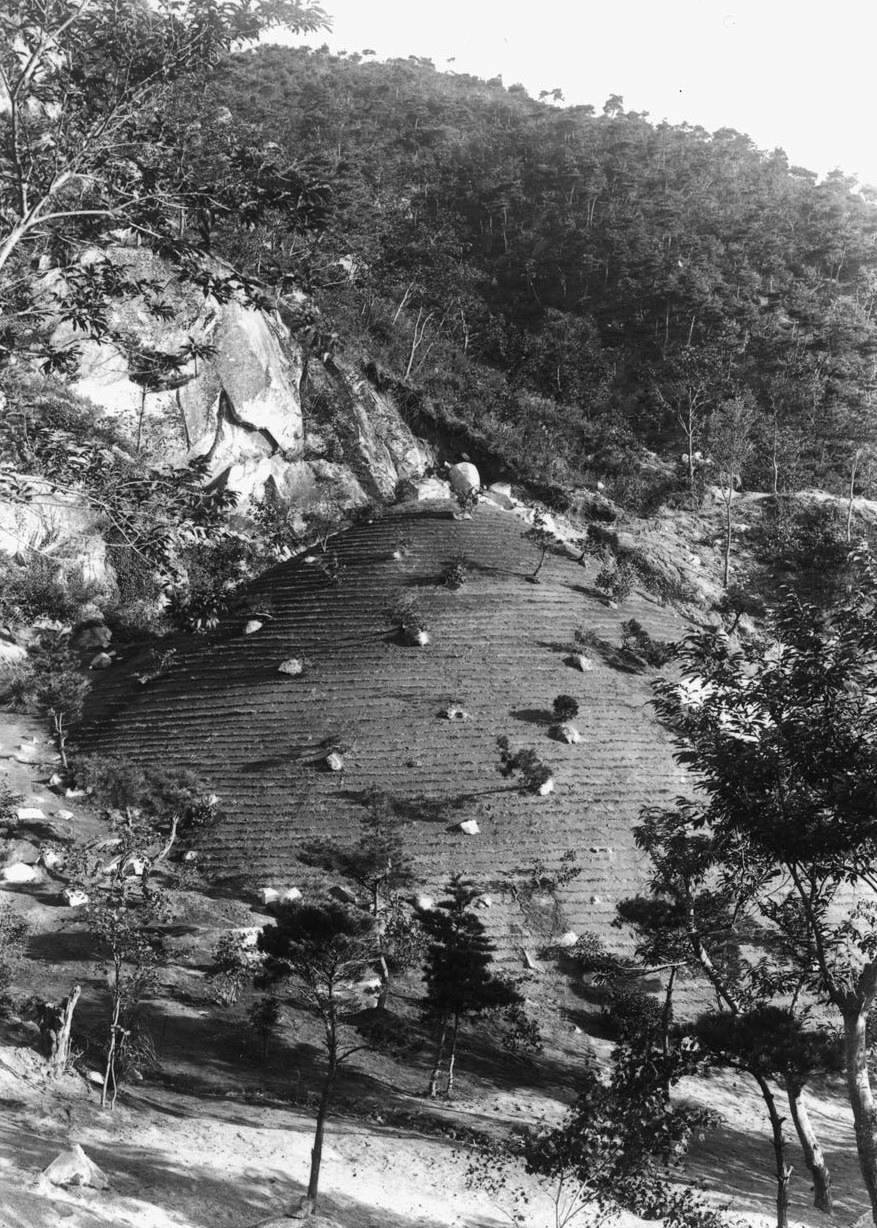

The first of these repairs lasted from 1913 to 1915, and it focused on the cleaning of the grotto and stabilizing the structure. The way they stabilized the structure was by encasing the structure in concrete, which was the most advanced technology at the time. Unfortunately, this led to humidity building up in the grotto, so a second round of repairs took place starting in 1917 when drainage pipes were added to remove rainwater from around the structure. Despite these efforts, a third round of repairs was conducted on Seokguram Grotto from 1920-1923, when waterproof asphalt was added to the surface of the concrete. Unsurprisingly, this only worsened the problem. So in 1927-1928, the Japanese did the now unthinkable when they sprayed the surfaces and sculptures inside the grotto with hot steam to blast away the moss and mold that had accumulated inside the grotto.

After Japanese Colonial Rule, and in the 1960s, President Park Chung Hee ordered a major restoration project on Seokguram Grotto. The problem of temperature and humidity caused by Japanese reconstruction projects led to humidity building up in the grotto. The Korean restoration project led to the past problem being resolved by using mechanical systems. It was also at this time that a wooden superstructure was built over the antechamber. This remains a hot topic of debate by many historians who believe the grotto originally did not have such a structure blocking the view of the sunrise over the sea; and subsequently, cutting off the air flow into the grotto. It was also around this time that the glass barrier was placed in front of the antechamber to protect it from both humidity and visitors. And it was beyond this barrier, for one day only, that I was able to visit the inner recesses of Seokguram Grotto. For many visitors, being limited to view the grotto through the glass partition can be a bit disappointing, that’s why I was so interested in going beyond this barrier.

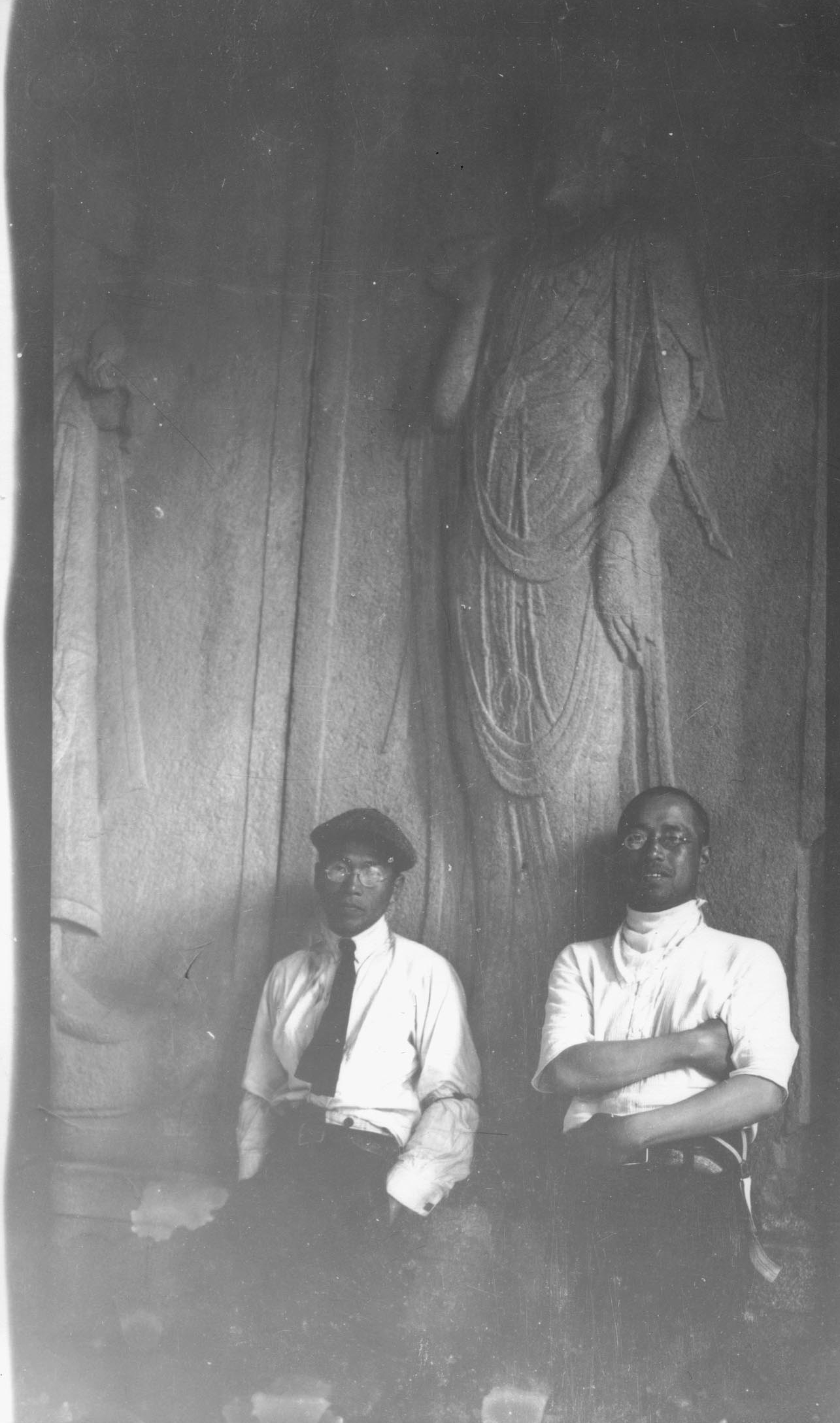

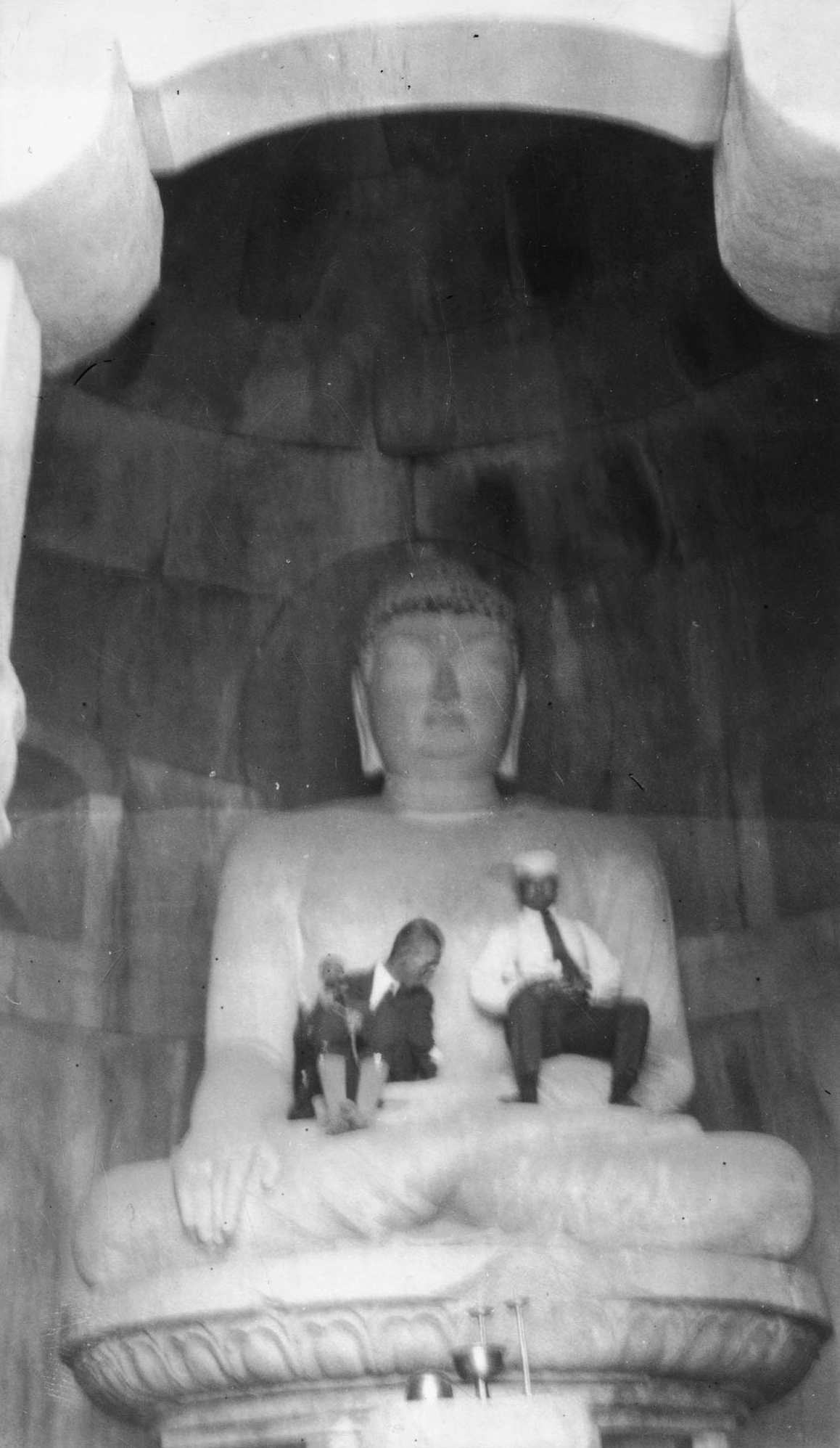

Pictures of Colonial Era Seokguram Hermitage

It should be noted that one of the reasons that the Japanese took so many pictures of Korean Buddhist temples during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945) was to provide images for tourist photos and illustrations in guidebooks, postcards, and photo albums for Japanese consumption. They would then juxtapose these images of “old Korea” with “now” images of Korea. The former category identified the old Korea with old customs and traditions through grainy black-and-white photos.

These “old Korea” images were then contrasted with “new” Korea images featuring recently constructed modern colonial structures built by the Japanese. This was especially true for archaeological or temple work that contrasted the dilapidated former structures with the recently renovated or rebuilt Japanese efforts on the old Korean structures contrasting Japan’s efforts with the way that Korea had long neglected their most treasured of structures and/or sites.

This visual methodology was a tried and true method of contrasting the old (bad) with the new (good). All of this was done to show the success of Japan’s “civilizing mission” on the rest of the world and especially on the Korean Peninsula. Furthering this visual propaganda was supplemental material that explained the inseparable nature found between Koreans and the Japanese from the beginning of time.

To further reinforce this point, the archaeological “rediscovery” of Japan’s antiquity in the form of excavated sites of beautifully restored Silla temples and tombs found in Japanese photography was the most tangible evidence for the supposed common ancestry both racially and culturally. As such, the colonial travel industry played a large part in promoting this “nostalgic” image of Korea as a lost and poor country, whose shared cultural and ethnic past was being restored to prominence once more through the superior Japanese and their “enlightened” government. And Seokguram Hermitage played a part in the propagation of this propaganda, especially since it played such a prominent role in Korean Buddhist history and culture. Here are a collection of Colonial era pictures of Seokguram Hermitage through the years.

Pictures of Colonial Era Seokguram Hermitage

1909

Pictures of Colonial Era Seokguram Hermitage

1914

Pictures of Colonial Era Seokguram Hermitage

1915

Pictures of Colonial Era Seokguram Hermitage

1918

Pictures of Colonial Era Seokguram Hermitage

1935

Pictures of Colonial Era Seokguram Hermitage

1936

Pictures of Colonial Era Seokguram Hermitage

Specific Dates Unknown (1909-1945)